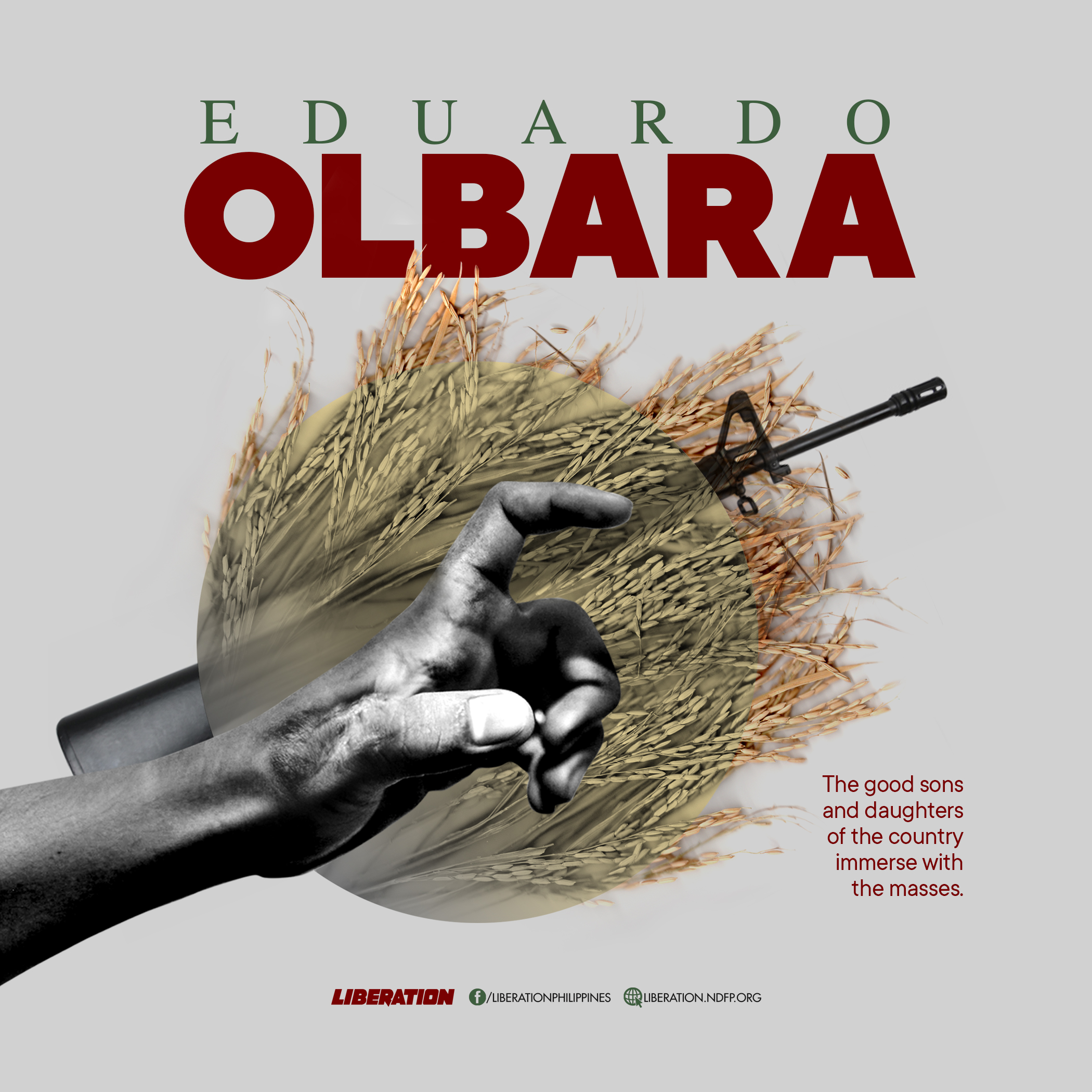

EDUARDO OLBARA COMMAND-NPA CAMARINES SUR

Adapted from Punla, the revolutionary literary publication of Bicol

The good sons and daughters of the country immerse with the masses, join them in their struggle and devote their lives in changing the unjust social order for a future devoid of oppression and exploitation. They do not only master the art of war but they rise above human frailties of ambition, grandeur and self-aggrandizement. They observe organizational discipline and practice simple collective life.

The person behind the Eduardo Olbara Command of the New People’s Army in Camarines Sur, Eduardo Olbara or Ka Andoy was one among the flock. Born to a poor peasant family, he left grade school to help the family. They own a piece of land but its paltry produce was not enough to sustain their needs. Even if they worked in the abaca plantation to augment their revenue, it was never enough.

A REVOLUTIONARY HAS BLOSSOMED

His father was among the first persons that Romulo Jallores (Ka Che) got in touch with when the latter returned to Camarines Sur, his hometown. Ka Che’s group was the first to start mass work and organizing in Bicol and later formed the first unit of the New People’s Army (NPA) in the region.

Every time Ka Andoy came home from his work in Laguna, he had fruitful discussions with the group. These raised his awareness and understanding of the problems plaguing society. From there dawned the realization of the need for revolution.

In 1973, after coming home from work, he decided to go on fulltime with the group. His elder brother had gone on fulltime before him. July of that year, he joined the group in its mass work in the boundary of Buhi, Camarines Sur and Polangui, Albay. That was the time when state armed forces were in full deployment in Camarines Sur.

NIP IN THE BUD

Earlier on in 1972, enemy forces began their massive and coordinated military campaigns against the very first guerrilla zone in the province in an attempt to snuff out the burgeoning revolution. The revolutionary forces in Camarines Sur confronted the rampaging Task Force Isarog of the enemy. They tried to skirt the patrols and strike operations of the battalion-strong Philippine Constabulary. But the intensive military operations resulted in the shrinking of the mass base. In December 1973, the NPA unit was left with only three barrios to operate in.

To preserve the forces, the NPA unit decided to transfer from Camarines Sur to Albay. Ka Andoy was part of the remaining squad that retreated and became the first Armed Propaganda Unit in Albay. There, they seized the opportunity to consolidate and strengthen the forces. From there, they managed to expand to other places and return to the guerrilla zone they left behind.

BRANCHING OUT

In 1974, Ka Andoy was assigned to communication work with the Bicol Technical and Liaison Staff (BTLS) based in the city. However, in December of that year, a series of arrests took place. When Ka Andoy eluded arrest, he was immediately deployed to the countryside.

Thus, from 1975 to 1980, Ka Andoy was one of the cadres in Albay assigned to the armed propaganda unit (Sandatahang Yunit Pampropaganda, SYP) for expansion work. Here, he honed his teaching and propaganda skills, as well as his ability to mobilize the peasant masses. He also effectively initiated the agrarian revolution by leading the campaigns for lowering of rentals in the haciendas.

Through earnest assessment and summing up of his rich experience in warfare, Ka Andoy enhanced his skills in military work. He became one of the best military cadres in the revolutionary movement.

During an encounter in 1979, his left hand was hit by a bullet that caused a deformity—as if his hand was holding the hand guard of an armalite. This had been his hallmark since then, a sign of readiness for battle.

In the first Party regional conference in 1981, Ka Andoy was elected member of the CPP-Bicol Regional Committee. He was assigned to oversee the front committee in Albay. He headed the work of the first district. He also guided the District Guerrilla Unit covering the towns of Oas, Libon, Ligao and Guinobatan.

In 1982, he led an ambush which became one of the most remarkable tactical offensives that gained military and political victory. He led the NPA unit’s ambush of the 564th Engineering and Construction Battalion operating in the boundary of Camarines Sur and Albay. This battalion had just replaced the former 52nd Philippine Constabulary Battalion. The head of the Battalion, Col. Laberinto was killed.

Simultaneous with tactical offensives, agrarian revolution was launched. The campaign to decrease land rental in the first district of Albay in 1982, called Oplan Pakyaw, became a provincial mass campaign in 1983.

In 1985, from the Front Committee, Ka Andoy was transferred to the new full company formation in Albay. He was designated as the first commander of the company formation deployed in Southern Bicol (Albay and Sorsogon).

After a political-military training in Brgy. Mabayawas, Libon, Albay in June 1985, the company was put on a defensive when attacked by the enemy. However, due to the superb tactics and maneuver of the revolutionary force, it managed to fend off the enemy’s advance. The enemy was overrun and suffered tremendous loss of lives, especially because it even had a misencounter with its own reinforcement troops.

The entire NPA company was able to maneuver safely without any one killed nor wounded. This encounter, which lasted for six hours, was the first recorded longest battle in Bicol between the revolutionary forces and the state forces.

The following year, Ka Andoy led two successive ambushes in Brgy. Banao, Oas and Brgy. Binogsacan in Guinobatan. The ambushes were notable for their effective application of guerrilla warfare.

In 1986, Ka Andoy was designated the first vice regional commander of the Regional Operational Command. He participated in the planning of military campaigns and assisted in the conduct of political-military trainings in the region. Despite his multifarious activities as troop commander, Ka Andoy shared in the day-to-day chores. He gathered supplies. He cooked. He also spent time socializing with the troops in their light moments. This established his closeness with his comrades.

Ka Andoy valued the welfare of his comrades highly but he never expected any special treatment. He was also fully aware of the role each red fighter had to take in their collective tasks that was why he could lead effectively. Ka Andoy’s comrades and the masses did not hesitate to approach him. He was truly concerned of their wellbeing. He was easy to deal with. One would readily feel at ease with him. He was gentle and courteous.

He was quick to notice if a comrade had a problem. He personally talked to him and gave his advice. He always tries to help his comrades, find solutions to their problems. Former comrades also sought him for consultation.

Ka Andoy abided strictly to the policies of the revolutionary movement. If he had reservations regarding certain issues and policies, he registered his reservation but he complied to what was decided or voted upon by the majority of the collective.

Ka Andoy was adept with techniques and tactics. He competently led big tactical offensives. He joined actual intelligence work. In actual encounters, he advanced with his troops but he assured that he was in full control of the entire fight. During tight situations, he never left his comrades.

Ka Andoy was a good and loving father and husband. He was solicitous for his three daughters. Yet he was open to sacrifice. He would endure being separated from them for a long time. He never dilly-dallied to entrust his children to the masses. He had full trust that they will take good care of them.

Even before the Second Great Rectification Movement, Ka Andoy was one of those who had reacted to the ill-effect of the untimely regularization of the troops as he witnessed the dwindling of the mass base.

Ka Andoy was killed in a defensive battle in Brgy. Alanao, Lupi, Camarines Sur on April 14. 1989. He was supposed to attend a meeting when the house where they stayed was encircled by the enemy.

In honor of his valiant and meritorious contributions to the struggle, the provincial command of the New People’s Army in Camarines Sur was named after Eduardo Olbara Command, Ka Andoy in the revolutionary movement.#