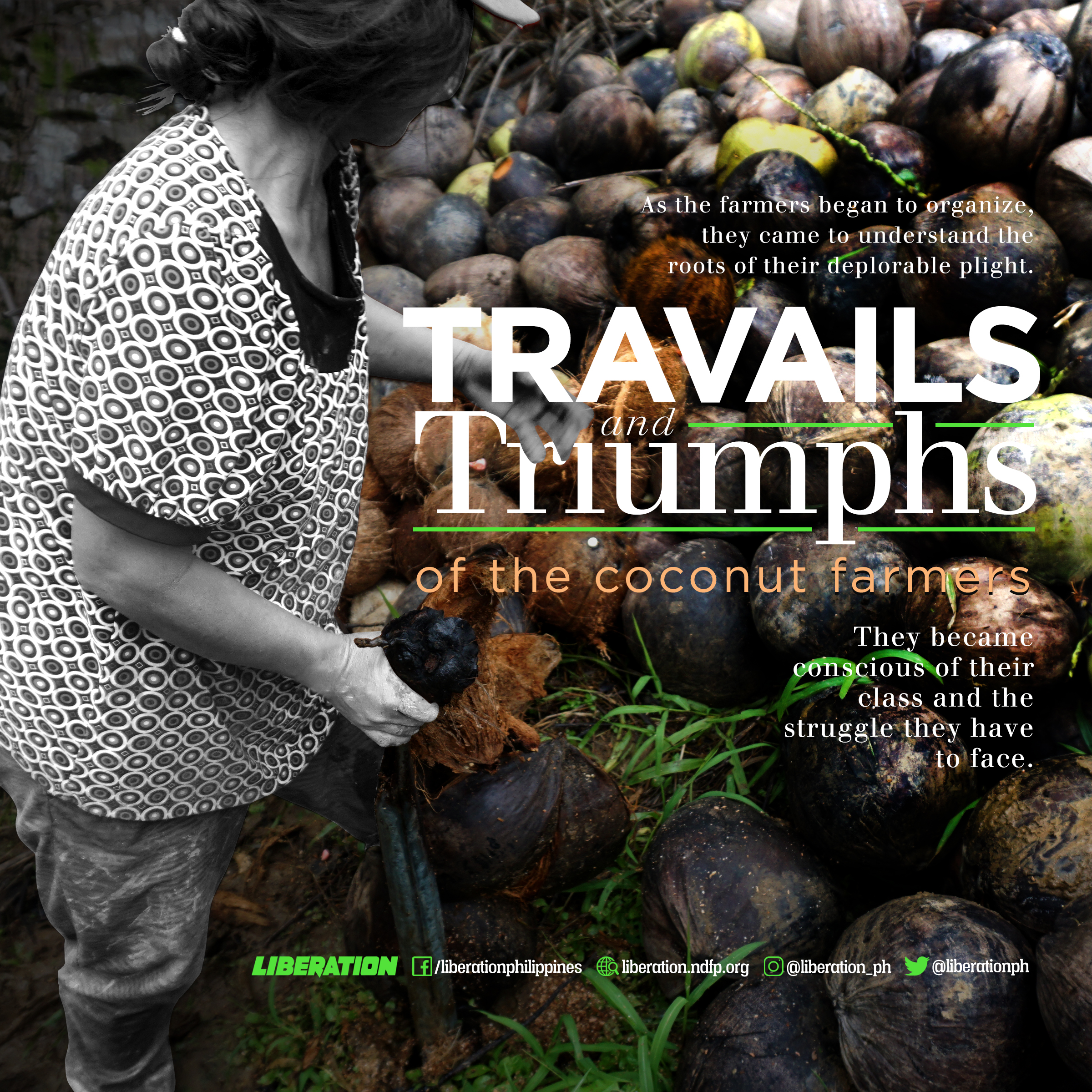

Travails and Triumphs of the Coconut Farmers

Within the last two weeks of February 2019, Pres. Rodrigo Duterte vetoed two bills concerning the coco levy funds that belonged to the coconut farmers. One bill would have created a trust fund for the coconut farmers and the other, the reconstitution of the Philippine Coconut Authority—the latter’s approval was a requisite in the creation of the Coconut Farmers and Industry Trust Fund. Now that the two bills had been vetoed, whatever semblance of action there is to save the ailing Philippine coconut industry and the coconut farmers, whether directly or indirectly, are now again put on hold.

THE COCO LEVY FUND

The coco levy fund was a tax imposed on small-time coconut farmers during the Marcos dictatorship, purportedly to develop the coconut industry. However, said coconut levy fund never benefited the farmers. Instead, this was siphoned to corporations of Marcos’ cronies. Succeeding regimes used various means to continue to hold on to the Php 150 billion coco levy fund, failing to return the huge amount of money to its rightful owners.

The farmers’ demand for the return of the coco levy fund was answered by a legislative bill creating a trust fund that will be managed by a reconstituted Philippine Coconut Authority (PCA). According to the bill, the Php 100 billion of the trust fund will be invested in government securities, the proceeds of which are promised (again) to be returned to the farmers. The development of the industry, which will be implemented by the PCA, has an annual budget appropriation of Php10 billion. The executive branch has no part in overseeing the implementation.

The reconstituted PCA is composed of a 15-person board, seven members of which are supposed to come from the private sector (a coconut industry stakeholder and coconut farmers from Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao with two representatives each.). Duterte vetoed the bill because he did not want private persons to influence the disbursement of “public funds” or he did not want to be left out from the control of the coco levy fund?

Congress will come up with a revised version of the bill. Meantime, the coconut farmers are in for another long haul. They will have to wait again for decades for the fruit of their sweat and blood.

AN AILING COCONUT INDUSTRY

Beyond the coco levy fund issue is a coconut industry that is on the brink of a collapse—affecting almost four million coconut farmers cultivating 26% of the agricultural land in the country.

An article recently published in Ang Bayan, (official publication of the Communist Party of the Philippines), cited several factors in the deterioration of the industry. One, natural calamities exacerbate the miseries of the coconut farmers. In 2013, the horrendous typhoon Yolanda hit the Visayas and ravaged their crops. In Leyte alone, 33 million coconut trees were destroyed. Aside from the typhoon, the coconut pest cocolisap also attacked.

But, the government did not only neglect the cause of the farmers by failing to provide subsidies and sufficient facilities to improve coconut production; it also brought man-made disasters.

It doesn’t help that the unabated land conversion and Duterte’s “Build, Build, Build” projects defraud thousands of farmers of the source of their livelihood. Most land conversions are in regions planted to coconuts—Southern Tagalog, Central Luzon, and Misamis Oriental. Land conversion benefits only the landlords/compradors and foreign investors who rake profits from eco-tourism, infrastructure projects, mineral exploration, palm plantation, real estate, cattle-raising, exotic fruits production etc.

FARMERS’ LAMENT

According to the same article published in Ang Bayan, 60% of coconut farmers and farm workers earn below the government-mandated minimum wage.

Every day in the coconut plantation is a struggle to survive. Each day the coconut farmers face the arduous tasks of preparing the coconuts into beneficial raw materials for industry, not only locally but also globally. Each day they toil to enrich the landlords/compradors, traders and transnational corporations in the US and Europe who have monopoly control of the price of palm oil.

Some farmers have a small parcel of land to plant their crops. But most of them pay rents to the landlords for the use of the land through sharing of the proceeds from the sale of the copra. Some just sell their labor power in plantations.

The process to produce copra, the marketable raw material from the coconut is a tedious job. It starts from the plucking of the fruits from the trees, gathering and piling them up. Under the heat of the sun through the chill of the nights, the coconut farmers husk the coconuts one by one before hacking them into two. Then they pile them over improvised grills to cook. Cooking takes a long time, depending on the quantity of the harvest. When there are still some not fully cooked these are returned to the grills. Removing the meat from the shell would require another overnight job. The cooked flesh or copra are hacked further then placed in sacks ready for the traders. Others still dry them under the sun before packing in sacks to further reduce the moisture content. Normally, the cooking process takes two weeks but in vast plantations owned by landlords, it lasts for a month. All in all it takes 45 days from the time of the harvest to complete the copra processing cycle.

Traders buy the copra at P18 per kilo. The price may differ from town to town but what is constant is the low price. The sale from a kilo of copra cannot even buy a kilo of rice, especially now that inflation has worsened because of TRAIN. In some cases, landlords who own oil mills, also act as traders. They buy the copra from the farmers at an even lower price—Php 17 per kilogram.

Coconut planters do not get all the proceeds from the sale of the copra. The traders deduct from the total cost of the copra produced the following: expenses for food and transportation (6%), the wages of nine farm workers who assisted in processing (18.4%), the cost of sacks, and the deduction due to lost moisture content (22%). The coconut farmers get only 17.8% from the sale while 36% goes to the landlords as rental to the land. This is a sharing of 1/3 is to 2/3 between farmer and landlord with the lion share going to the landlord. The deduction due to the loss of moisture content is unilaterally determined by the traders.

Some coconut farmers who own the land prefer to sell their produce as is to avoid the laborious process of making copra. But just the same the Php 3.00 to Php 5.00 per whole coconut could hardly meet their needs. Even the farm workers hired occasionally to help in the copra processing exist from hand-to-mouth with a measly wage of Php 4.00 to Php 7.00 a day.

In companies processing coconut oil, farm workers’ income is from Php 200.00 to Php 300.00 for every 1000 coconut harvested and processed. In the Peter Paul Philippines Company, 1,500 workers are contractual and not receiving enough salary. With the TRAIN law, the workers’ income has dropped from Php 20,000/year to Php 7,200/year.

The Philippine Coconut Authority (PCA) has remained mum, to say the least, on the unabated decline of the prices of copra and coconut. In some instances it cites the global competition as an excuse, or the oversupply of copra.

Meanwhile that the landlords/compradors, traders and transnational corporations profit and relish from the fruit of the farmers’ labor, the latter’s families at times just content themselves with a miserly meal of rice dashed with coconut milk.

PEASANTS EMPOWERMENT

As the farmers began to organize, they came to understand the roots of their deplorable plight. They became conscious of their class and the struggle they have to face. They realized that when united they are a potent force more powerful than the handful of greedy ruling class grappling for power and wealth.

Life in the coconut plantations is still penurious but no longer precarious. They have perceived a way out of bondage, out of the mercy and control of landlords/compradors, traders and imperialists corporate interests. The herculean tasks in the coconut plantation seemed lightened.

With their new-found strength, they demanded for a better share from the proceeds in the sale of their produce. From the 80-20 percentage sharing, it has become 67-33 percentage today in many areas of the country.

In the town of San Antonio in Southern Tagalog, coconut farmers succeeded, but not without fanfare, in asserting their right to plant root crops for their subsistence between rows of coconut trees. Likewise, the collective mass actions of peasants launched on October 3-4, 2017 in Brgy. Camflora, San Andres, Quezon, in connection with the campaign “Balik-Saka sa Hacienda Uy (Return to Farming in Hacienda Uy)” have won for them the right to till the 385 hectares of coconut and agricultural land of Dr. Vicente Uy for free. Last year, peasants from South Quezon, in Bondoc Peninsula launched a campaign and held mass actions demanding the government to raise the price of copra.

In guerrilla fronts, the Pambansang Katipunan ng Magbubukid, PKM (National Association of Peasants), a revolutionary mass organization of peasants affiliated with the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP), charts revolutionary agrarian reform programs in varying degrees—from reduction of land rental and farm inputs prices to a maximum of land ownership transfer from despotic landlords to farmers. The PKM also thwarts government’s anti-people and pro-landlords and foreign investors land conversion plans. The New People’s Army (NPA) while fighting renders support and protection to the PKM’s programs and to the organs of political power set up in the guerrilla zones. The peasantry, firmly believing that only through armed struggle can they be truly liberated from bondage, graciously offers their good sons and daughters to boost the main force of the national democratic revolution.