Gilbert Torres: The Artist is a Revolutionary

by Pat Gambao

Art transcends beauty when it serves the struggling masses and fires the revolution. Art becomes a weapon of war, and as such it becomes a weapon of peace.

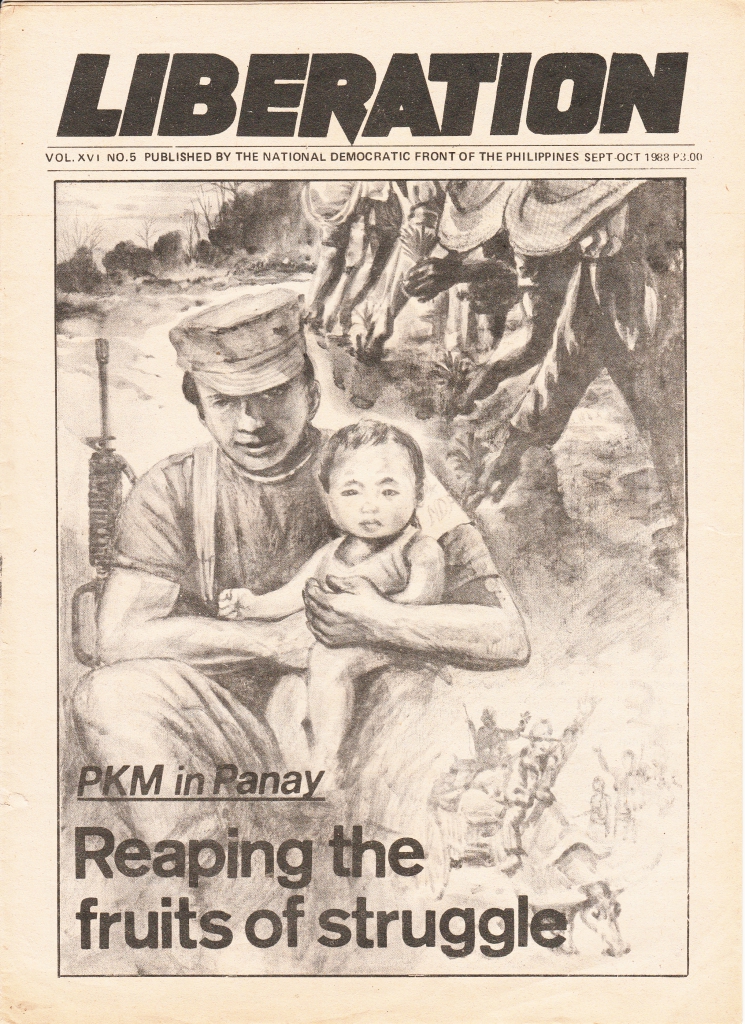

Gilbert Torres’s artworks, which effused the sense of commitment and principle, passion and dedication, were spread in the pages of revolutionary publications, such as the Liberation of the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP), the Ulos of ARMAS (Artista at Manunulat para sa Sambayanan), an organization of artists and writers allied to the NDFP, the education materials of the Commission on Education of the Communists Party of the Philippines (CPP), and the protest paper, Sick of the Times, a lampoon of the evils of the Marcos dictatorship.

Gibet, as he was fondly called, started his activism during his senior year at Don Bosco Technical College. It had not been difficult to kindle in him a sense of nationalism, and even the revolutionary spirit. His grandfather was an Irish-American who had been in the Philippines since the early nineteen hundreds. Gibet had always been proud of his Irish descent having known the valiant struggle of the Irish people for independence from British rule. He had idolized the Irish Republican Army. Of course, he was also aware that in his veins likewise flowed the heroic blood of his Filipino forefathers who for centuries had fought against foreign invaders. Thus, in his fondness for books, what created great impact on him were stories of people’s struggles for liberation and love for freedom.

It was never difficult for him to associate with the masses. He studied in a school the orientation of which, as founded by its namesake (St. John Bosco, an Italian priest), is a school for the poor. But as a private sectarian school owned and operated by the Salesian Congregation that St. John Bosco also founded, it had become also a school for the affluent. As he loathed the hypocrisy of the elite Gibet was more comfortable in the company of his schoolmates who were in relatively lower social strata or in the same petty-bourgeois class where he belonged. As a member of the Nationalist Corps, an organization of the youth in Don Bosco, he immersed with the peasants and workers.

As a fine arts student at the University of the Philippines (UP) in the 70s, he provided art works to the “rebel” Philippine Collegian, a parallel publication handled by student activists at the time when the official campus paper was in the hands of the “reactionaries”. In those days, before the advent of electric typewriter, photo stencil and IBM typesetting machine, computer and Risograph printers, underground papers used manual thin stencils to type in articles. Mimeograph machine was used for printing. Art works were done more exhaustively using a pointed steel, called stylus pen, on the delicate stencil paper. Extreme care was required. Gibet did his art works, meticulously, superbly.

With the abolition of student councils in 1973, following the declaration of martial law, student activists in UP worked hard to put up the Student Conference Committee on Student Affairs or CONCOMSA. Gibet was its representative from the UP College of Fine Arts. In other campuses, students also moved to form progressive student organizations. These bodies pushed for the restoration of student councils. The students’ struggle for their democratic rights in the campuses became a part of the broader anti-fascist struggle of that time.

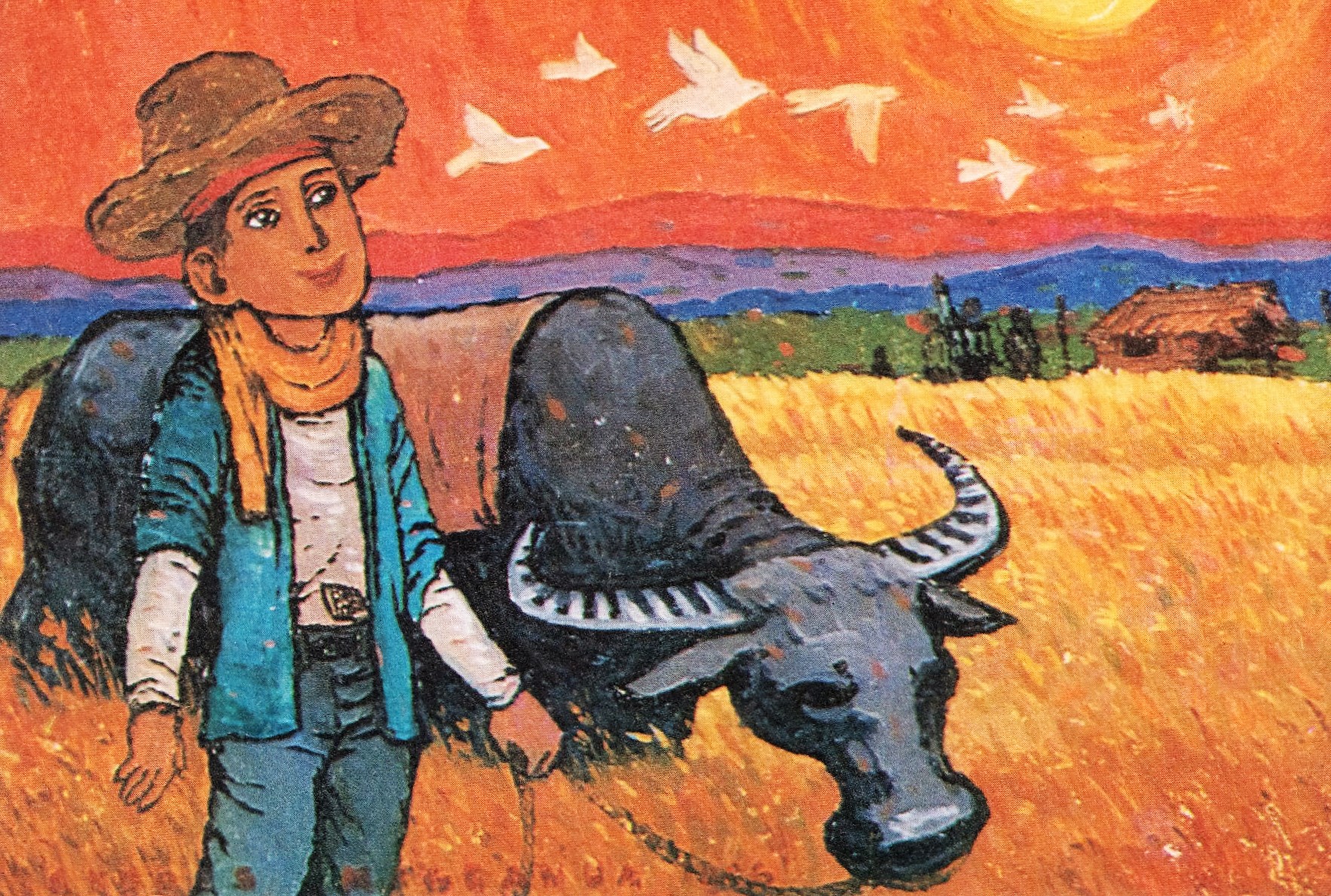

With his exposure, as a member of the Nationalist Youth or Kabataang Makabayan (KM), to peasants and farm workers and to the underground movement, Gibet’s art work assumed a new dimension. The influence of his favorite Italian painter Fra Filippo Lippi and German painter and printmaker Albrecht Durer was probably still there but infused in the flesh and actions of the revolting peasants, the striking workers, the restive students.

In April 1982, Gibet was arrested by military men as he was about to enter the Liberation underground staff house in Quezon City. He was carted off to the Bagong Bantay military camp in Quezon City and tortured. But despite the blows to his body and the gun pointed to his head, Russian-roulette style, he staunchly stood his ground. The military failed to break him down and extract information from him. He was released after six months.

Upon release, Gibet had the time to bake his favorite Irish bread that his friends relished upon. He also spent time in Philippine solidarity groups for Latinos in El Salvador, Guatemala and Peru. He was also involved in the peasant campaigns in Hacienda San Antonio and in the Sta. Isabel Tabacalera land issue in Cagayan Valley.

Even when Gibet joined the mainstream arena of digital arts and advertising, he continued to do art works for the mass movement. For IBON Foundation, he had designed covers for calendars and did illustrations in its book TNCs Por Biginers. His standpoint never dwindled. It is immortalized in the verse by Jonas Leopoldo of ARMAS which was quoted in the NDFP greeting card where Gibet did an artwork under the nom de guerre Andres Magbanua: “Real and lasting peace is born out of struggle for freedom and justice.” To these days, Gilbert Torres’s life and works continue to inspire young revolutionary artists.