Duterte Wants to Grab Land Reform from the NPA

by PINKY ANG

On the 31st anniversary of the failed Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP) last August, President Rodrigo Duterte spewed lies against the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and the New Peoples’ Army (NPA). Preening before the media while giving out Certificates of Land Ownership Award (CLOA), he boasted he would finish the CPP-NPA-led revolution.

But this put-on picture—Duterte distributing CLOA < click >, Duterte tough-talking on Hacienda Luisita < click >, Duterte feigning concern for the future generation caught in the armed conflict < click >, Duterte promising land reform alongside crushing the 50-year people’s war < click, click >—is phony and old (he isn’t the first president to pose for it). It also defies logic and history.

Save for a fleeting period when he was talking peace with the communists, Duterte has done nothing but the opposite of land reform and national industrialization.

On the verge of signing with the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP) what would have been a landmark agreement to redistribute land for free all over the country, he scuttled the talks in 2017. Since then, he has made no bones in taking the well-worn path of his most despotic predecessors in Malacañang.

No Philippine president in history has truly implemented land reform nor attempted to jumpstart national industrialization spurred by a genuine land reform program. On the contrary, their so-called land reform programs sought only to placate the masses even as land remained in the hands of a few. From the bitter experiences of peasants, every land reform program by the Government of the Philippines had more loopholes than grounds to actually distribute land. And even when some eventually got distributed, it somehow got back soon enough to landlords.

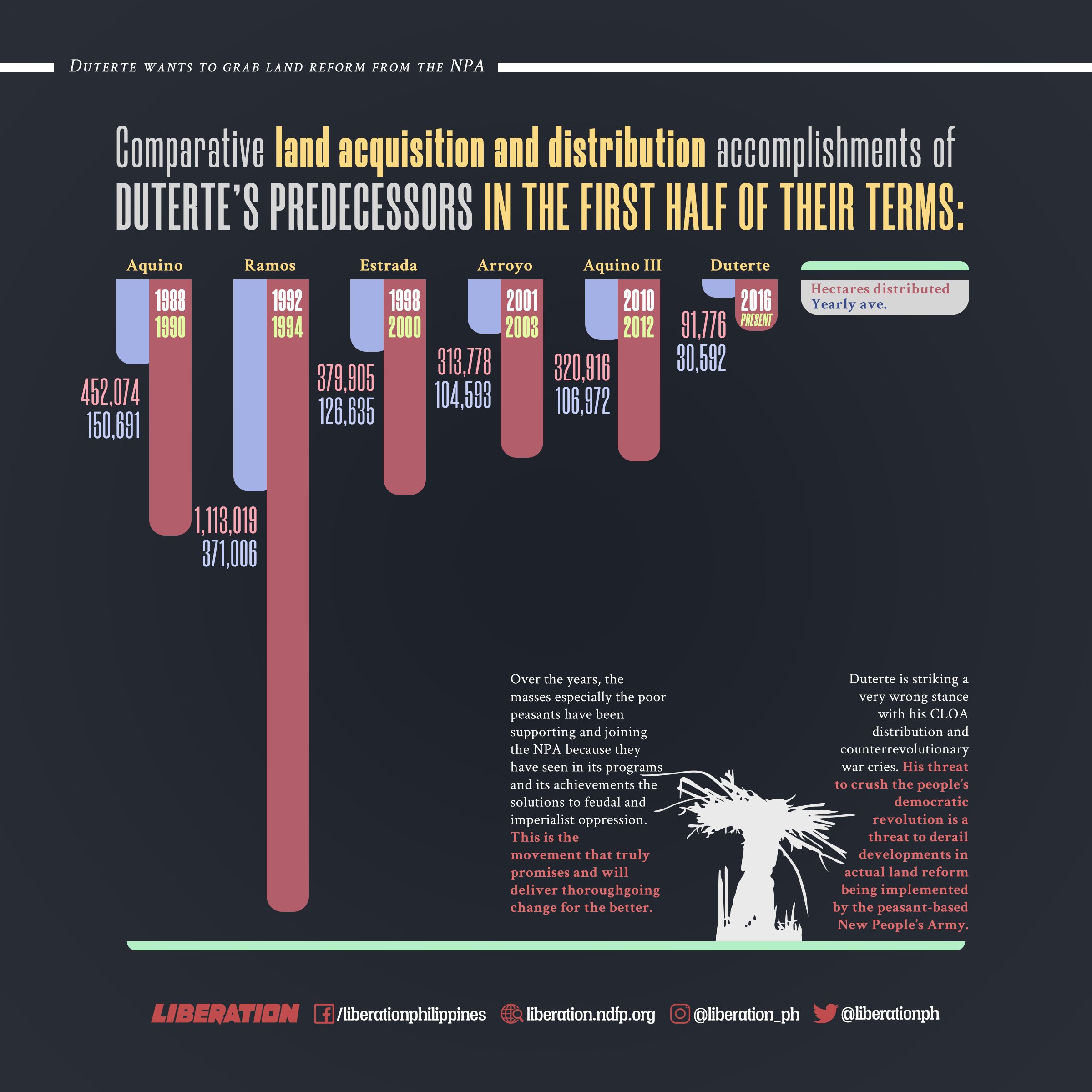

Duterte merely continued the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program begun under former Corazon Aquino. Despite decades and a succession of presidents and CARP extensions, it is still far from attaining 100-percent distribution of its already narrowed target. Under Duterte, distribution is at the slowest, poorest pace.

DAR records show that the Duterte administration, in its first three years in office, was able to distribute to farmer-beneficiaries only 91,776 hectares of agricultural landholdings. That’s an average of 30,592 hectares a year. His land acquisition and distribution (LAD) pace was only 8% of that of the Fidel Ramos administration in its first three years. Ramos was top performer among the previous presidents.

Here are the comparative LAD accomplishments of Duterte’s predecessors in the first half of their terms:

- Corazon Cojuangco Aquino: distributed 452,074 hectares from 1988 to 1990, or 150,691 hectares a year;

- Ramos: distributed 1,113,019 hectares from 1992 t0 1994, an average of 371,006 hectares annually;

- Joseph Estrada: distributed 379,905 from 1998 to 2000, or 126,635 yearly;

- Gloria Arroyo: distributed 313,778 hectares from 2001 to 2003, averaging 104,593 hectares per year;

- B.S. Aquino III: distributed 320,916 hectares from 2010 to 2012, or 106,972 hectares each year.

Data: Dept. of Agrarian Reform land distribution accomplishment in 2016 to June 2019 is 2,920 hectares on average per month under Duterte,

less than the July 2010 to 2015 monthly average of 8,254 has. reported by DAR under Noynoy Aquino;

9,407 has. under Arroyo in January 2001 to June 2010,

and 11,113 has. monthly average under Estrada.

There is a raging armed revolution in the Philippines because peasants and the basic masses, including sections of the middle class and local small capitalists, thirst for land reform. They yearn for the greater prosperity of industrialization that genuine land reform will naturally stimulate, and for the assured just distribution and sustainability of this prosperity because of the socialist perspective of the national democratic revolution being waged by the CPP-NPA-NDFP.

Over the years, the masses especially the poor peasants have been supporting and joining the NPA because they have seen in its programs and its achievements the solutions to feudal and imperialist oppression. This is the movement that truly promises and will deliver thoroughgoing change for the better.

Duterte is striking a very wrong stance with his CLOA distribution and counterrevolutionary war cries. His threat to crush the people’s democratic revolution is a threat to derail developments in actual land reform being implemented by the peasant-based NPA. It’s a threat as well to delay the country’s national industrialization. This is not acceptable to the Filipino masses who continue to suffer a life of misery under the landlord-comprador and imperialist puppet presidents including Duterte.

Another president who posed with CLOAs amid counterrevolutionary war cries was Joseph Estrada. In Bondoc Peninsula, after a series of successful NPA tactical offensives there 20 years ago, he vowed to crush the revolution movement. He became the second president to be ousted through the people’s peaceful direct action.

“WHOLE OF NATION” AS MARTIAL LAW UNDERCOVER?

By this time, as commander-in-chief, Duterte has already issued one too many orders— declaring and thrice extending martial law in the whole of Mindanao; declaring a state of emergency to quell “lawless violence” and issuing Memo 32 to deploy more troops in Samar, Negros island and Bicol; utilizing the so-called “whole-of-nation” approach that harnesses the entire government (national and local) plus civil society organizations in a bid to end the 50-year armed conflict. Clearly though, his actions contradict his boasts against the CPP, which his government shrilly tries to demonize and misrepresent as a puny force being deserted by droves of supposed surrenderers.

But, like the failed land reform program, Duterte’s “whole-of-nation” approach is just another war plan his predecessors have long applied and failed on. It is like the wolf appropriating the voice of the innocent so it can freely enter homes to devour and kill.

Duterte is turning the entire government bureaucracy including civilian sectors into a counter-revolutionary surveillance and black propaganda factory. Its services are being deployed to feed into the coercive military and police troops cracking down on legal democratic mass organizations, and their allies here and abroad. While this government is raining bombs and lies, it is restraining flow of information about the revolutionary movement. It is banning media interviews and coverage of revolutionary groups.

Duterte is trying to revive the monsters of Marcos’s martial law, but not quite succeeding at muzzling the freedom of association and freedom of the press. He goes all-out with K-12 miseducation that’s washing off traces of patriotism and prompts for critical thinking among the youth. All the while he is pushing for military partnership with schools to abet surveillance and intimidation of critical students and teachers.

PR-labeling all these as “whole-of-nation approach,” Duterte dreams about finishing off the CPP-led revolution but only through a one-sided, reality-defying, blood-drenched misrepresentation of life on the ground.

For this brutal fantasy, his office wants to double its intelligence budget to P4.5 billion in 2020, or bloat it to half as big as the total budget of the Office of the President. His minions in Congress seek to add more teeth to the anti-terror law they euphemistically call as Human Security Act. His regime and the US government have agreed to locate a regional training center for combating insurgency and “terrorism” in Cavite. The military consistently receives from the US technical and intelligence support, training and equipment for countering the revolutionary groups.

Yet, amid the Duterte regime’s one-sided diatribes against the CPP-NPA, some truths still inadvertently emerge. Some from his own big mouth. Duterte himself can’t deny the public support for the communist revolutionaries.

After all, he wooed the Filipino voters into electing him president by cultivating appearances of being friendly to the CPP- NPA. His campaign ploy has confirmed that candidates gain popularity by calling themselves “leftist” or “socialist”; by promising peace talks with the communists; and by taking up issues articulated by or identified with the Left. For example, the call to assert Philippine sovereignty in the West Philippine Sea vis-à-vis China’s aggressive intrusion into and grabbing of maritime areas within the Philippines’ exclusive economic zones.

Past presidents and presidential candidates publicly pretended to ignore the existence of revolutionary mass bases in the countryside, even when they were impelled to engage in peace talks. They fumed whenever “security concerns” delayed their visits to some locales, when candidates can’t simply enter guerrilla zones. They evaded disclosing the fears expressed by multinational corporations over another government operating clandestinely in the Philippines, which, unlike the reactionary government, calls them to task for their plunder and rights violations.

Perhaps Duterte, who claims to know a lot about the revolutionaries, panicked after he realized that the neocolonial institution he leads wouldn’t tolerate his slight deviation from the usual conduct of puppet presidents. Or, perhaps as a true neocolonial leader of landlord and comprador class (albeit with lesser money in his hands?) he panicked at his first-hand confirmation of the depth and breadth of the Left’s mass support.

Whatever, even when he was firmly following the tradition of imperialist puppetry of those who got to become temporary residents of Malacañang, he still inadvertently slips up, revealing in his ramblings the good things the CPP-NPA have been doing. For example, land reform.

But it would be political suicide for Duterte, or for any local government executive and for the AFP, to say outright that he is against land reform. To “win hearts and minds” and bar more people from supporting the revolutionaries, Duterte and his cohorts have to put deceiving masks to their war plans.

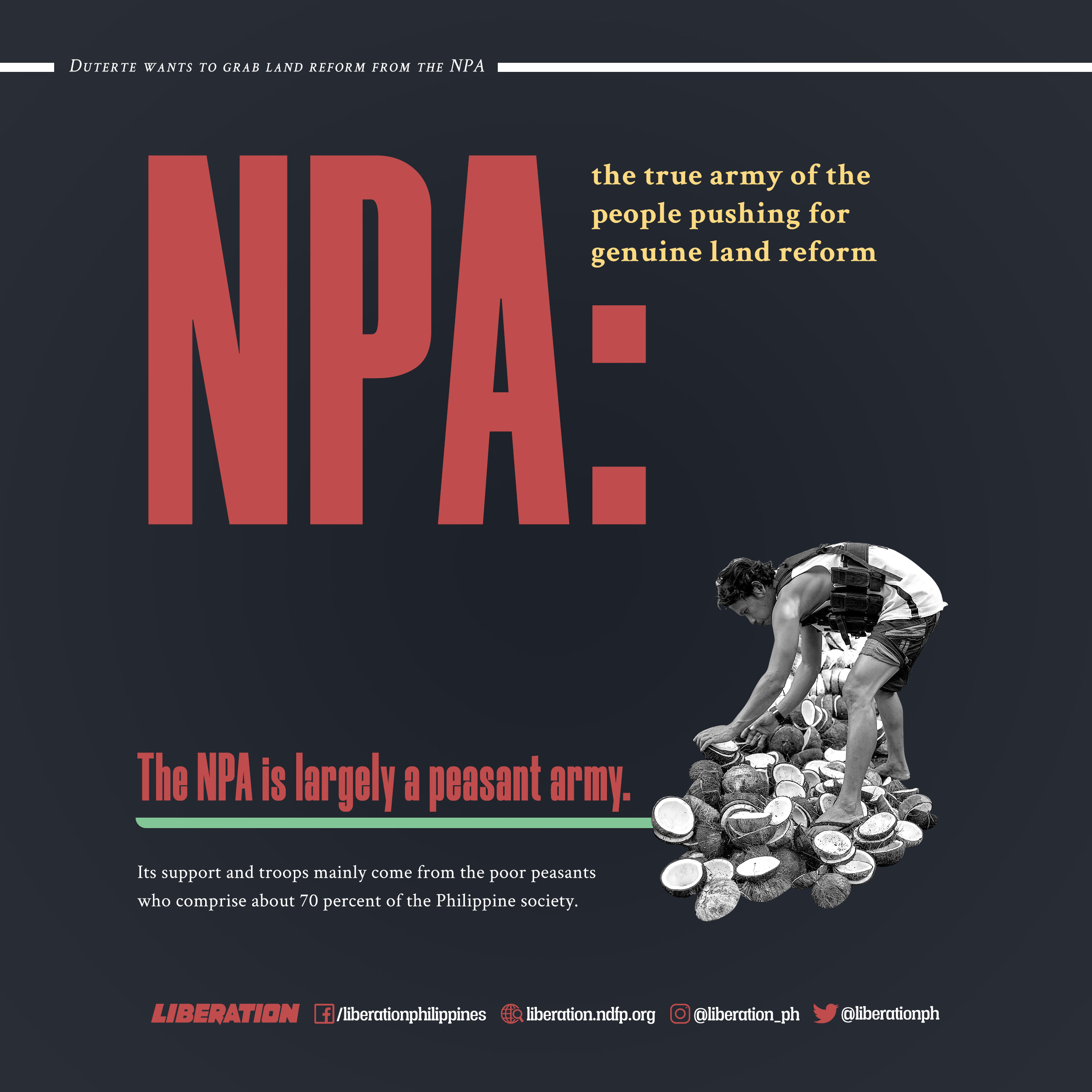

NPA: THE TRUE ARMY OF THE PEOPLE PUSHING FOR GENUINE LAND REFORM

The NPA is largely a peasant army. Its support and troops mainly come from the poor peasants who comprise about 70 percent of the Philippine society. As the army of the revolutionary people led by the CPP, the NPA is waging a revolution against the imperialist stranglehold on Philippine society. It aims to end this stranglehold by dismantling the puppet government that orchestrates and secures it to benefit the landlords and compradors. In the process, the NPA, under CPP leadership, is resolving with ever growing number of people the roots of poverty, landlessness, feudal exploitation, agricultural backwardness and the stunting of industrial development.

Ever since the CPP-NPA-NDFP began waging an armed revolutionary war, it has been pushing for genuine land reform. It is deriving greater strength the more it works to organize and help peasant communities undertake land reform.

The NPA is not just a military force. It is arousing, organizing, and mobilizing the masses. It is starting and helping the peasants into organizing and running the Pambansang Katipunan ng mga Magsasaka or PKM (National Peasants Association), and other revolutionary mass organizations based in rural communities.

These organizations conduct campaigns for land reform suited to their capacities. The more masses organized into revolutionary groups the more they could undertake land reform and enjoy its fruits. The more they cherish and bolster the NPA underpinning their successes.

A PKM leader correctly said recently, as the national democratic revolution advances, the PKM shall be able to give more lands to poor peasants. Lands confiscated from landlords and agri-business corporations are given to beneficiaries free of amortization. The CPP-NPA also punishes the most despotic landlords.

Contrast this to the misery of intensifying feudal and semi-feudal exploitation, and one sees the futility of discouraging the masses from supporting the NPA. In time, their level of organization and experience approaches the building of bigger and bolder organs of political power in communities. This may start small with humble benefits, but as a PKM leader said, it is enough for PKM chapters to withstand the hardships and tragedies of counterrevolutionary wars.

In revolution they have hope. And having tasted its benefits even from the early stage of strategic defensive of the protracted people’s war, they would not easily be swayed by phony pictures and declarations.

Thanks to the NPA, the country’s peasants have had a taste of what it’s like to be in a truly democratic government—at least, the local underground government they are building up every day, campaigns after campaigns for land reform. What it’s like to govern themselves, to elect tried-and-tested leaders among themselves, to work the farm sustainably, to share and enjoy its fruits among themselves and not let it become the sole entitlement of landlords, to help plan and execute appropriate farming techniques and technology.

The organized peasants are also doing their share in thwarting the imposition of imperialist-led “reforms” and programs.

The NPA has functioned to truly harness the power of the people in working collectively for each other’s economic and political gains.

“The comrades in the NPA are helping us come up with policies and guidelines in the land distribution, especially on who should be prioritized—those landless and those who lack lands to till,” said Ka Iling, a peasant leader who participated in a local agrarian revolution conference in 2017 held at a guerilla front in the north. It was a joint project of local members of the CPP, the NPA, and the various revolutionary mass organizations in the area.

All over the country, PKM and other collectives of revolutionary groups, without fanfare, have tackled problems of landlessness, conducted land occupation, palit-tanim (changing crops) to have something to eat even as they are forced to plant cash crops. They have struggled to reduce land rent and usurious rates. They have formed cooperatives to work the land more efficiently, buy their needs, and sell their produce lessening the dominance of traders-landlords-usurers.

Almost a million PKM members have benefited from the CPP and the NPA’s maximum agrarian reform program: more than 44,000 hectares of land have been confiscated and redistributed all over the country. Millions of others have benefitted from the campaigns for lower land rent, lower borrowing interest rates, just share in proceeds of harvest, increased farm gate prices, and eliminating traders’ trickery when farmers’ produce are weighed and priced.

Their support services include training and workshops on organic farming, construction of mini dams for free irrigation, installation of hydroelectric and solar or wind-powered turbines for post-harvest drying or processing, among others.

All these and its further development are what are at stake in the counter-revolutionary war waged by the Duterte administration.

THE COMMUNIST REVOLUTION ON A WINNING PATH

Farmers call Duterte a hypocrite for pretending to care about the future generation while doing his best to kill their best prospects today.

He was quoted as telling the CPP-NPA, “We cannot go on this way. We have been fighting for 53 years. Maawa kayo sa susunod (Have mercy on the) coming generation.”

If he was indeed a man of mercy, he could have helped signal the end of armed fighting early into his term. When he terminated the peace negotiations in 2017, the two sides were on the cusp of signing an agreement prompting the Philippine government to implement a genuine land reform.

A clearly-defined mutually coordinated ceasefire would have followed.

As such, even before the massacres occurred in the hacienda land of Negros, or before the killings of peasants all over the country have reached a staggering number of victims (more than 200 as of August 2019 since he became president), the Duterte government could have halted the fighting. For the first time in history, it could have led to the neocolonial government helping resolve the peasant demands which are at the root of the prolonged armed conflict.

Instead, Duterte only confirmed the correctness of the people’s war as means to dismantle the neocolonial government by armed force. His regime has acted true to form in deploying more troops against the peasant-based NPA fighters. Duterte himself acted true to form like the other neocolonial leaders before him. He vowed to sell to highest bidders the fertile lands being defended by the peasants with their very lives.

His agricultural secretary accused the farmers doing bungkalan for survival that they have no rights to the land they should have owned already. He has also been approving with alacrity the appeals of landlords to defeat the farmers’ demands for land distribution. This includes the lands in Hacienda Luisita already ordered for distribution by the Supreme Court.

Duterte admits that “it’s not only about gaining a foothold in those areas,” referring to hotbeds of revolution like Negros, for example. In Sagay City where peasants awaiting CLOAs were massacred by paramilitary troops in October 2018, farmers have been forced to leave and go hungry as troops continue arriving to secure the landlords’ “lawful” ownership. How could the Duterte administration think they could win over these farmers?

Duterte himself admits it is not enough to just bring soldiers to guard the land. “Kunin mo na ang initiative sa komunista (Take the initiative from the communists). What they’re parlaying is land. Eh di unahan na natin. Bigay na natin [ang lupa] (Then let’s move ahead of them. Let’s distribute the land already).”

From the puppet leader who has repeatedly uttered lies and shamelessly admitted to uttering lies, the only true thing he revealed here is that the initiative on land reform is with the communists.

Ever since, the puppet government bowing to imperialist masters has only been reacting to the peasants’ demands for land with bogus land reform programs. The imperialists profit so much from dumping their surplus agricultural products here, while pushing their manufactured products, too. As long as the domestic industries are pushed back and stunted, they have a captive market. The landlord and comprador classes, meanwhile, win big in corruption, buy-and-sell profits, fat contracts and commissions. But the masses grow poorer and hungrier by the day.

Four years ago before Duterte, the poorest 50 percent or 11.4 million Filipino families subsisted on just P15,000 or less per month (P500 or less per day for a family of six). After tax and price hikes amid the lowest wage grants and the worst job generation in the post-Marcos period, the people are definitely worse off today under Duterte. Meanwhile, thanks to his economic policies, the net worth of the country’s richest and the profits of the largest corporations have ballooned.

“Crisis generates resistance,” as CPP founding chairman Jose Maria Sison titled one of his recent books. The peasantry had launched uprisings and died in bigger numbers before, without the communists to guide them. Now that they have tasted agrarian victories and glimpsed the best future in advancing the national democratic revolution, with socialist perspective, they have hope and will not likely give up on that.

Duterte’s “whole-of-nation” mantra for what he strains to approximate as martial law stands no chance. His human rights record already stinks with blood and many have recoiled from it, even the ordinary people in other countries.

His publicly paid troops who perform services for the landlords, oppress the peasants and the indigenous peoples, will continue to earn the people’s ire and mistrust. Duterte’s minions can conveniently dismiss their war crimes as “shit happens” and “collateral damage”. Before the media, Duterte can shed tears when his troops suffer defeat in legitimate combats with the New People’s Army.

They will keep on getting what they deserve from the people’s army, if they don’t stop standing in the way of genuine land reform, democracy and real prosperity for the majority of the people. #

#PeasantMonth

#ServeThePeople

#JoinTheNPA

—–

VISIT and FOLLOW

Website: https://liberation.ndfp.info

Facebook: https://fb.com/liberationphilippines

Twitter: https://twitter.com/liberationph

Instagram: https://instagram.com/liberation_ph