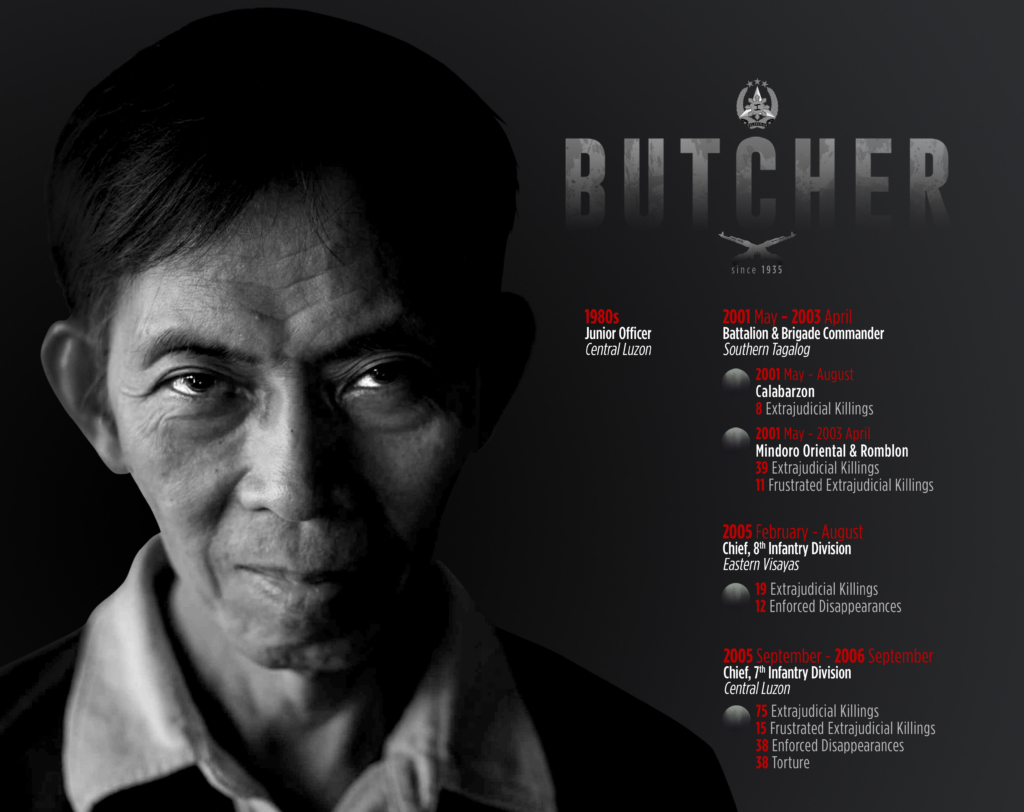

JOVITO S. PALPARAN Jr., “THE BUTCHER”: Contemptuous of Right to Life and Justice

by Angel Balen

He is gaunt and awkward in physical bearing, lisping in speech, unimpressive for a military officer.

Yet, on his 56th birthday on September 14, 2006, Jovito Palparan Jr. ended 34 years of service in the Philippine Army with the rank of Major General and a hoard of military medals (ranging from bronze to gold).

His shining moment came in July 2006, during President Gloria Arroyo’s state-of-the-nation address before the joint session of Congress: she called on him to stand up in the gallery and gushingly hailed him as her favorite general.

But in the hearts and minds of the informed public, Palparan has been a truly detestable public figure.

When Gloria Arroyo lavishly praised him, the human rights community—national and international—was outraged. Long before that inglorious day, human rights defenders had been roundly condemning him. They excoriated him for his brutal counterinsurgency methods: killing, abducting and torturing mass leaders and activists—noncombatants all—from 2001 to 2006.

A presidential investigating commission on the killings, created in 2006, noted in its report that “there was a rise in the extrajudicial killings of activists and militants between 2001 and 2006, as compared to a similar period prior thereto.” The killings followed a pattern, wherein “victims were generally unarmed, alone, or in small groups and were gunned down by two or more masked or hooded assailants oftentimes riding motorcycles.”

The commission’s head emphasized: “It is undisputed that the killings subject of the investigation of our Commission did not occur during military engagement or firefights. These were assassinations or ambush-type killings, professional hits carrying one out quickly and in the silence escaping with impunity.”

The killings were verified to have risen fast in the three regions of the country to which Palparan had been assigned (Southern Tagalog, Eastern Visayas, and Central Luzon).

The gory operations he started in the Southern Tagalog region, particularly in Mindoro, were topped by the brutal abduction and murder of human rights defender Eden Marcellana and peasant leader Eddie Gumanoy in April 2003. Investigations by the House of Representatives human rights committee resulted in the identification by witnesses of Palparan’s long-trusted executioner, MSgt. Donald Caigas, as the one who led the perpetrators.

It was in Southern Tagalog that Palparan earned the derisive monicker, “The Butcher.” And he seemed to have derived supreme pride for being called that, as the star performer in human rights violations under the Arroyo regime’s two-phased counterinsurgency program, Oplans Bantay Laya I and II.

Anti-communist viciousness

Liga ng mga Manananggol para sa Bayan (LUMABAN)

But inevitably the time of reckoning for Palparan’s crimes had to come. And it came on September 17, 2018—12 years after he retired from military service.

On that date, the Malolos Regional Trial Court Branch 15, presided over by Judge Alexander Tamayo, convicted Palparan for just one of the numerous crimes attributed to him: kidnapping with serious illegal detention (with torture) and disappearance in June 2006 of former University of the Philippines students, Sherlyn Cadapan and Karen Empeño. He was sentenced (along with two other Philippine Army officers) to a prison term of 20 to 40 years.

Palparan’s behavior, before and after the reading of the verdict, starkly provided a peak into what sort of a person he is.

Apparently, he is basically a coward. But he covers up such weakness with arrogance and belligerence.

Take, for instance, how he was brought in and out of the courtroom on that day he was convicted, as he was in every hearing of the case over four years. From the Philippine Army headquarter’s detention area (where he presumably enjoyed a sense of security), he would put on a military helmet, surrounded by a phalanx of soldiers bodily shielding him upon arrival at the courthouse.

Inside the court, while waiting for the judge to come out, he feigned self-confidence as he told a news reporter who queried him, “After this, we walk as free men. We are not guilty.”

After the court verdict was read, however, Palparan instantly transformed himself into a boor. He yelled at the judge, “Duwag ka, judge! Duwag ka, tarantado! (You’re a coward, judge! You’re a coward, jerk!).“And when the judge warned he might be cited for contempt, he shot back, “It doesn’t matter anymore. We’re going to prison anyway.”

It took quite a time before “The Butcher” was finally charged in court and put on trial.

In 2007, under strong public pressure, President Arroyo formed a commission to investigate the more than 100 cases of extrajudicial killings that occurred under her watch. Retired Supreme Court Justice Jose A.R. Melo headed the body (thus, it was called the Melo Commission). In its 89-page report, the commission pointedly recommended Palparan’s prosecution. But nothing happened.

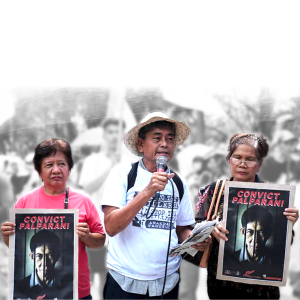

Meantime, the mothers of Sherlyn and Karen painstakingly sought recourse through petitions of habeas corpus filed with the Court of Appeals and the Supreme Court. Their efforts paid off. Aided by human rights lawyers, the mothers—Erlinda T. Cadapan and Concepcion E. Empeño—filed a complaint against Palparan and his military cohorts in May 2011.

When the preliminary hearings on the case began, Palparan tried to slip out of the country but he was stopped at the airport. After he was indicted in December 2011 he went into hiding to evade arrest. Only after he was arrested in August 2014 did the trial proceed, with many interruptions at the instance of Palparan’s lawyers.

The Butcher is now confined at the National Penitentiary (Bilibid Prison) in Muntinlupa City, among other maximum-security convicted criminal inmates. His lawyers have filed an appeal for reconsideration of the court’s verdict.

The basis of the appeal is quintessentially Palparan’s vicious anti-communist line. It asks the court to review its “erroneous appreciation of the written statement and testimonies of the [key] witness, Raymond Manalo, who is under the protection and support of the Communist Party of the Philippines.”

It was during his deployment as Army unit commander against the New People’s Army (NPA), after an eight-year assignment in Sulu to fight against the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), that Palparan consistently built up and demonstrated his utter ideological, anti-communist viciousness.

As he was promoted to higher ranks, Palparan turned more arrogant, self-righteous, bigoted, and fascistic.

His viciousness was manifested in a stream of extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, and massacres mostly victimizing noncombatant activists and civilians—as affirmed in the report of the Melo Commission. Its investigation focused on 136 incidences of extrajudicial killings (EJKs) previously verified as true by the Philippine National Police’s Task Force Usig, another probe body created by Arroyo.

At the National Consultative Summit on Extrajudicial Killings and Enforced Disappearances, initiated by then Chief Justice Reynato S. Puno in July 2007, Justice Melo made a brief oral presentation of the commission’s report. He quoted some of Palparan’s statements to the media that more than tended to acknowledge or confirm his role in the spate of EJKs.

Among those statements are the following:

“I want communism totally erased—to wage the ongoing counterinsurgency by neutralizing not just the armed rebels but also a wealth of front organizations that include leftist political parties, human rights and women’s organizations, even lawyers, and members of the clergy.”

“My order to my soldiers is that if they are certain that there are armed rebels in the house or yard, ‘Shoot them!’ It will just be too bad if plain civilians are killed in the process. We are sorry if you are killed in the crossfire.”

“Would there be some collateral damage [once the soldiers shoot]… But it will be short and tolerable. They [referring to critics of his methods] blow it up as massive violations of human rights, but to me it would just be necessary incidents. Sori na lang kung may mapatay na sibilyan (it’s just too bad if civilians are killed). The death of civilians and local officials were small sacrifices brought about by the military anti-insurgency [campaign operations].”

On the extrajudicial killings in the areas he was assigned as field commander, Palparan was more voluble and cocky. Here are some of his statements that Melo cited:

“They [EJKs] cannot be completely stopped. I would say they are necessary incidents in a conflict because they [the targeted victims] are violent. It’s not necessary that the military alone should be blamed. We are armed, of course, and are trained to confront and control violence. But other people whose lives are affected in these areas are participating [in the armed conflict].”

“The killings are being attributed to me. But I did not kill them. I just inspired the triggerman.”

“I am responsible, relatively perhaps… But in the course of our campaign, I could have encouraged people to do that—so maaaring may responsibility ako doon (so maybe I am responsible). I don’t want that aspect, but how could I prevent it? We are engaged in this conflict. All of my actuations have been designed to defeat the enemy. And in doing so, others might have been encouraged by my actions.

“Whoever it is, who could have been encouraged by my actions and actuations in the course of my campaign [against] whoever they are. That is why I say relatively. If these are soldiers, maybe then I could have been remiss in that aspect. But we are doing our best to keep our soldiers within our mandate.”

As regards the progressive party-list organizations that had won seats in the House of Representatives, whose members had become EJK victims since 2001, Melo quoted Palparan as having said the following:

“A lot of the members are actually involved in atrocities and crimes… Even though they are in government as party-list representatives, no matter what appearance they take, they still are enemies of the state.

“The party-list members of Congress are doing peace to further the revolution of the communist movement. I wish they are not here.”

“We can draw our own conclusions from these statements,” Melo told the participants in the Supreme Court-initiated consultative summit.

He pointed out that all of the victims of the 136 EJK incidents were activists, were “generally unarmed, alone, or in small groups and were gunned down by two or more masked or hooded assailants oftentimes riding motorcycles.” The assailants, he added, “surprise the victims in public places or their homes and make quick getaways.”

Also, “it is of note that the military in general called the victims as enemies of the state who deserved to be neutralized, according to the testimony given to us,” Melo added.

(Significantly, the Malolos RTC Branch 15 decision convicting Palparan also states: “Clearly, General Palparan was one [with others] in the desire to stamp out the enemies of the state, like Karen and Sherlyn, who they believed deserved to be erased from the face of the earth at any cost.”)

The investigation also established that “the PNP had not made much headway in solving the killings,” Melo said. Only 37 cases had been forwarded to the proper prosecutor’s office.

Also speaking for the House of Representatives at the National Consultative Summit in July 2007, then Makati Rep. Teodoro Locsin Jr. commended the Melo Commission Report as “complete, comprehensive and fair… and forthright in its conclusions and recommendations.”

He noted that the Melo Report says, “the signs are abundant and cannot be ignored that General Palparan had actively encouraged the men under him, in at least three areas he was assigned as field commander, to ‘neutralize’ activists tagged as ‘enemies of the state.’ ” This is a category [“enemies of the state”] that “does not exist in law, conventions of warfare or articles of war,” said Locsin, who is a lawyer-journalist.

On this point, the Melo Report concluded: “By declaring persons enemies of the state, and in effect, adjudging them guilty of crimes, these persons have arrogated unto themselves the powers of the courts and of the Executive branch of government.”

On this point, the Melo Report concluded: “By declaring persons enemies of the state, and in effect, adjudging them guilty of crimes, these persons have arrogated unto themselves the powers of the courts and of the Executive branch of government.”

“To be sure,” Locsin pointed out, (Palparan) denied ordering any killings but granted that he may have inspired the triggerman. Congress [through its Commission on Appointments] reacted swiftly confirming his promotion in time for his long-awaited retirement,” he added wryly.

“The Melo Commission pointedly recommends General Palparan’s prosecution on command responsibility: either for not stopping his men from carrying out the killings or for encouraging a climate conducive to the commission of these crimes by security agents,” the congressman noted, and he agreed with it.

And for good measure, Locsin shared that, through his questioning during a House of Representatives public hearing on the EJKs, “Palparan would not categorically deny that under his command there are special teams operating at night, wearing bonnets, or masks, with the apparent mission of extrajudicial elimination of so-called enemies of the state.”

By these accounts of Palparan’s offhand statements or replies to questions, both from the media or congressional investigations, he is totally capable of incriminating himself, whether unwittingly or wittingly—and braggingly at that! On the The Butcher’s “would-not-categorically-deny” stance, Locsin mischievously remarked, “Apparently, he feared the prospect of being charged with perjury rather than murder.”

In Duterte’s rein as the commander in chief of the AFP, Palparan would have been his perfect collaborator, joining the other Gloria Arroyo generals Hermogenes Esperon of the National Security Council and Eduardo Año of the Interior and Local Government.

Duterte is president and commander-in-chief and Palparan a mere pawn in the chain of command but, both feel they are gods in their own right, gods spawned by a debased system of class divisions.

Both Duterte and Palparan have intense abhorrence of communists and desperately dream of crushing the national democratic revolution. Both would dismiss the call for peace as a way to further the revolution. Palparan would readily smell blood (and be nourished by it) from Duterte’s order to neutralize not only armed rebels, but also activists, supporters, and “would-be rebels”. Both would arrogantly ramble of claiming full responsibility which inspire and spur killings and violence unmindful of innocent victims they dismiss as collateral damage.

Duterte may have outshone Palparan with his boorish, misogynistic remarks and acts against women as well as with his blasphemous tirades of God. But like Palparan, Duterte will suffer the same ignominious fate when the people’s wrath and justice catch up with him.