ANOTHER ARREST, ANOTHER OBSTACLE TO PEACE Release Esterlita Suaybaguio!

The National Democratic Front of the Philippines Negotiating Panel condemns the illegal arrest and detention of Esterlita Suaybaguio, consultant of the NDFP in the peace negotiations with the Government of the Republic of the Philippines (GRP). Suaybaguio’s arrest is another obstacle to the peace talks which the Duterte regime wants to bury.

Suaybaguio is covered by the Joint Agreement on Safety and Immunity Guarantees (JASIG) with Document of Identification (DI) Number ND 978447 as second consultant for Mindanao. A copy of her DI is deposited in the safety deposit box under the name of Archbishop Joris A.O.L. Vercammen.

The Duterte regime remains on a fascist rampage that adds more and more obstacles to the resumption of the peace negotiations with the NDFP.

Since the unilateral termination of the talks in November 23, 2017, a number of NDFP personnel, including consultants Vic Ladlad, Adel Silva and Rey Casambre, have been rounded up and continue to be imprisoned based on trumped up criminal charges. The Duterte regime’s violations of previous agreements such as The Hague Joint Declaration and the JASIG show its contempt for the aspirations of the Filipino people to achieve a just and lasting peace.

Instead of creating the conditions to enable the resumption of the negotiations, the Duterte regime has unleashed fascist attacks all over the country, especially in Mindanao under martial law as well as in Negros, Bicol and Samar under de facto martial law. To date, Duterte’s Executive Order No. 70 has resulted in the murder of over a hundred activists from different sectors in Negros.

The “anti-insurgency” campaign of the Duterte regime continues to wreak havoc to the human rights of the Filipino people. Duterte’s Proclamation 374 designating the CPP-NPA as so-called terrorist organizations is also used to tag critics of the Duterte regime and social activists as “terrorists” and justify the most brutal attacks against civilians and whole communities marked as bases of the revolutionary movement.

Instead of promoting just peace, the Duterte regime and its military even send psywar and spy teams in schools and communities and even abroad to muddle the facts about the peace talks, sow disinformation on activist organizations and NGOs, and hide the widespread extrajudicial killings and rampant human rights violations in the country.

The NDFP Negotiating Panel calls for the immediate release of Suaybaguio and the dropping of false charges against her, as well as the scores of other detained NDFP consultants and personnel. The intensifying acts of terror manifest the scheme of the Duterte regime to impose fascist dictatorship on the Filipino Nation. ###

REFERENCE:

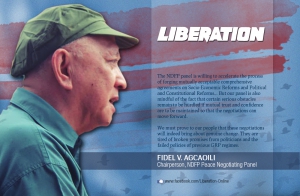

Fidel Agcaoili, Chairperson

NDFP Negotiating Panel

August 26, 2019