Breaking Away from the Usurious Farm Traders

by Priscilla de Guzman

The road leading to the village was mostly rough and muddy, with a few meters of cemented portion after every few kilometers. Where there was a cemented road, harvested corn crops were spread over it on plastic sheets to dry under the sun.

“You were lucky, kadua (comrade in the Ilokano language),” Ka Efren told me as he expertly maneuvered his motorcycle through the muddy parts of the road. “It has been raining for weeks. The rain stopped only two days ago, he said.

Ka Efren’s community occupies a public land, a forested area, where titling is not allowed by the government. However, some enterprising local government officials and trader-usurers have been able to acquire land titles through sheer bribery. The public lands have been home to most of the farmers, such as Ka Efren, since birth.

As we passed through another batch of harvested corn being dried, Ka Efren muttered how low the prices that the traders pay for their produce. “I don’t know how much I’ll earn this harvest season, our corn harvest was not properly dried because of the rains,” he lamented.

Embracing victory

Ka Jong, the other motorcycle driver, quickly reminded Ka Efren that, just two days ago after the rains had stopped, a farmers’ organization in a Cagayan Valley municipality won its battle against the usurious traders. The good news, he said, had spread like fire in the neighboring communities, towns, and even in other provinces in the region. Ka Efren’s face immediately lit up. Yes, he suddenly remembered.

We arrived at the community where the farmers had gathered as members of a local chapter of the Pambansang Katipunan ng mga Magsasaka or PKM (National Peasants Association), one of the founding member-organizations of the National Democratic Front of the Philippines [NDFP]). They were exultant over the victory of the mass action-cum-dialogue with the traders—a victory won through a militant show of unity in demanding that the traders pay justly for the farmers’ produce and do away with their usurious practices.

The peasant leaders who joined them can understandably claim much of the credit for the triumph. They were fired up in narrating their collective action, what they had gone through before they achieved victory. They took turns in pointing out how they had been exploited by the trader-usurers. The latter had monopoly and control of everything the farmers needed from planting to harvesting. They also dictated the prices of their corn and cassava produce. It had been a full cycle of exploitation.

The peasant organization’s victory of getting a fair shake from the traders meant the following: reduced interest rates on their loans, higher selling prices for corn and cassava crops, reduced prices of the sacks used in packing their produce, and a reprieve from interest payments they had incurred during the super typhoon Lawin that hit the region in 2016.

Monopoly of the traders

For a long time, loans and interest payments had chained the farmers to the trader-usurers. Without capital to buy seedlings of their choice, the farmers were compelled to plant BT-corn and cassava for cash crops used as animal feeds.

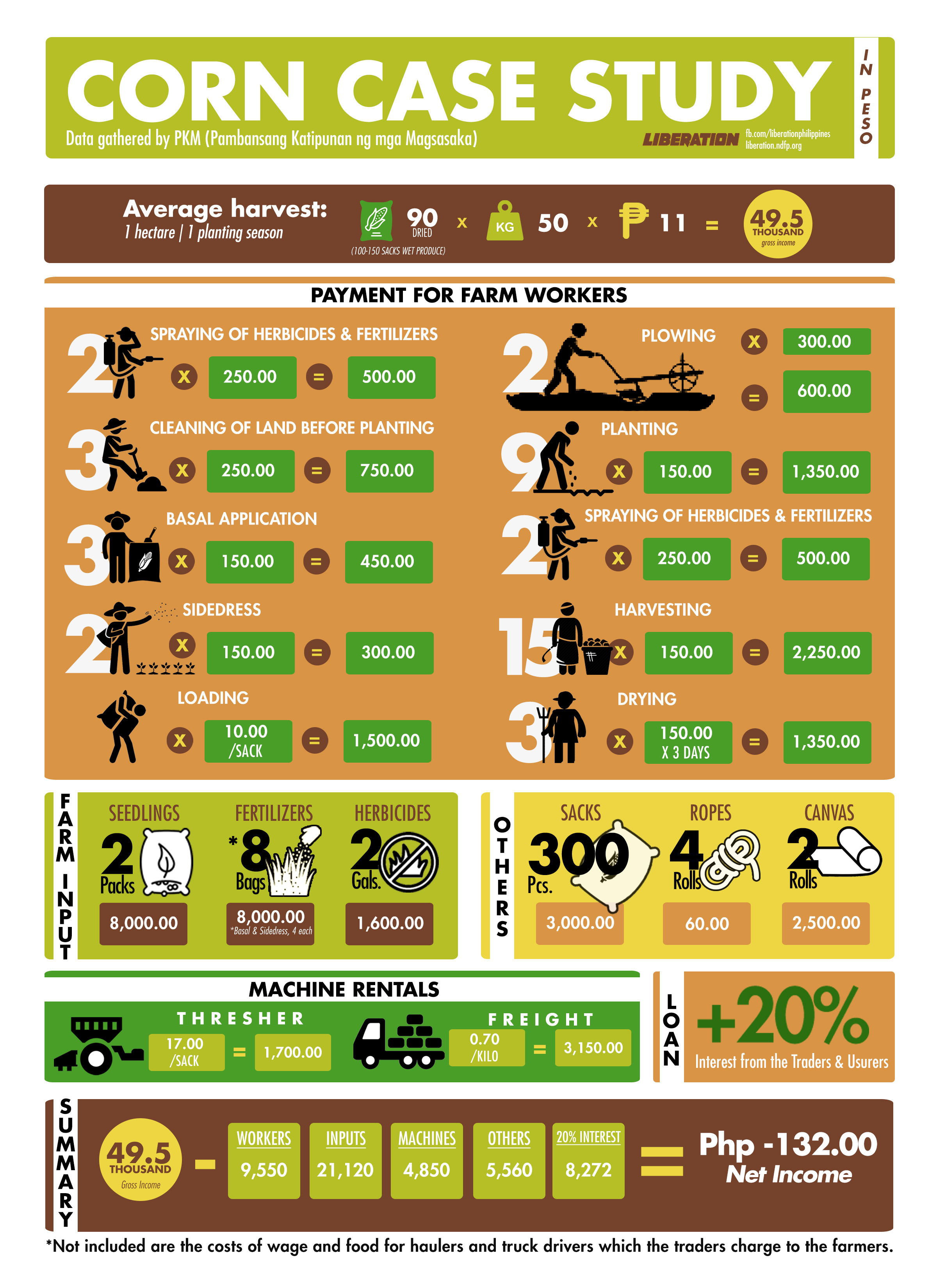

The seedlings were sourced as loans from the traders, who also provided them with fertilizers and herbicides as loans. During harvest, these same traders bought the farmers’ produce at a price they practically dictated, based on their own grading and weighing systems—wherein trickery was usually employed. After the harvest, the farmers ended up practically with nothing in their pockets, or worse, with another sheet of paper where their additional loans and interest payments were listed down.

Most atrocious was the trading of sacks used to pack the harvests. The farmers buy the sacks at Php10.00 each from the local traders who bought these for Php5.00. Per harvest, they have to buy 300 sacks costing Php3,000. The farmers use the sacks to bring their produce to the local traders who, in turn, use these when they sell to the buying stations. These sacks were never returned to the farmers. Thus, when another planting-harvest season starts, the farmers would again spend for the sacks.

Cagayan Valley is the country’s top producer of BT-corn, with genetically modified organisms (GMO), and farmers like Ka Ludy and many others in his community had contributed much to its propagation, at their expense.

The Department of Agriculture introduced the BT-corn in the early 2000 but the people widely rejected it. Not long after the trader-usurers were acting as aggressive conduits for its propagation, leaving no choice for the penniless peasants but to accept, as BT-corn was the only available seedling the traders would loan to them.

“It’s as if the traders got to hire planters and laborers without salaries,” said Ka Ludy. There was a time, when there was no available food for them, some farmers tried to eat BT-corn to find out if it was fit for human consumption. Result: they developed allergies.

Breaking away from the traders

Energized by the recent victory of the farmers, the PKM members are more determined to go on with the plans they had laid out during the AgRev (Agrarian Revolution) conference held in the last quarter of 2017. The conference was a joint project by local members of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), the New People’s Army (NPA), and the various revolutionary mass organizations in the guerrilla front.

During the conference, the peasants resolved to vigorously push for the palit tanim (literally, changing plants) campaign. As an initial step, the PKM collectives in the different villages would start planting food crops to ensure food on their tables as they moved to break away from the trader-usurers’ dictates.

“The seedlings were donated to us by friends and we will divide these among the collectives in the different villages,” Ka Ludy explained. With a steady supply of food on their tables, the farmers can then start planting cash crops of their choice, sell directly in the market individually or collectively, and earn what they have worked for.

“In the long run, this will allow us to do away with the seedlings supplied by the traders and gain freedom from their monopoly and exploitation,” he said.

Land distribution and communal farms

The 2017 AgRev conference was the first held in this guerrilla front after more than a decade. In the conference, the revolutionary organizations also lined up plans on maximizing the utilization of idle lands in their communities and those nearby. The local Party and NPA units and the PKM plan to distribute some 50 hectares of land among the 30 poorest peasant families.

“The comrades in the NPA are helping us come up with policies and guidelines in the land distribution, especially on who should be prioritized—those landless and those who lack lands to till,” said Ka Iling, a participant in the AgRev conference.

Aside from the individual effort to plant food crops in their palit tanim campaign, a substantial portion of the land for distribution will be allotted for communal farming and food production for the needs of the revolutionary mass organizations and the NPA units.

“There have been already existing communal lands in different villages, probably for more than 10 years now. But the lands are too small for our needs,” Ka Iling pointed out. “So, aside from these existing communal farms, we could work on a bigger piece of land to augment our needs,” he continued. The members of the Party branches and revolutionary mass organizations, he said, could work together and produce more crops.

Minimum and maximum program of agrarian revolution

The efforts of Ka Ludy, Ka Iling, Ka Efren, Ka Jong and other members of the PKM in this community exemplify the unity of the peasants nationwide to carry out the agrarian revolution led by the Party, the people’s army, and the NDFP.

Already, almost a million PKM members have benefited from the Party and the NPA’s maximum agrarian reform program where more than 44,000 hectares of land were confiscated and redistributed all over the country. Millions of others have benefited from the campaigns for lower land rent, end to usury, just harvest proceeds, increased farm gate prices, and elimination of trickery when produce are weighed and priced.

Only the revolutionary movement led by the CPP-NPA-NDFP can proudly lay claim that, in its almost 50 years of existence, it has slowly but steadily freed the peasants from the hundreds of years of feudal bondage.