Freeing Political Prisoners: A Matter of Obligation and Justice

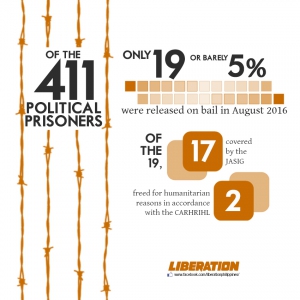

The release of over 400 political prisoners is a key issue in the peace negotiations between the Government of the Republic of the Philippines (GRP) and the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP).

The NDFP stands on just ground when it calls on the GRP to release all political prisoners in compliance with the agreements previously signed by the two parties, specifically, the Joint Agreement on Safety and Immunity Guarantees (JASIG) and the Comprehensive Agreement on Respect for Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law (CARHRIHL). Both parties reaffirmed the validity of the CARHRIHL and JASIG in a joint statement on Aug. 26, 2016 and also during the third round of talks in Rome, Italy on January 2017. They also completed the supplemental guidelines for the full implementation of the CARHRIHL.

The CARHRIHL, signed and approved in 1998, guarantees the immediate release of prisoners who have been charged, detained, or convicted with common crimes instead of political offenses like rebellion or sedition. Part III, Article 6 of the CARHRIHL states that the GRP “shall abide by its doctrine laid down in People vs. [Amado V.]Hernandez… and shall forthwith review the cases of all prisoners or detainees who have been charged, detained, or convicted contrary to this doctrine, and shall immediately release them.”

The majority of the more than 400 political detainees has been charged with trumped-up and common non-bailable crimes—a serious violation of the CARHRIHL and the Hernandez “political offense” doctrine, which was upheld by the Supreme Court in many instances. The release of the political prisoners, therefore, is a state obligation and not a favor being handed by the GRP. Hence, this is not a mere matter of confidence building measure for the peace talks.

President Duterte himself agrees that the practice of criminalizing political acts is unjust; a practice that was started under the Corazon C. Aquino government. In a meeting with NDFP leaders and consultants at Malacanang Palace in August 2016, Pres. Duterte promised to stop the practice of criminalizing the actions of political prisoners in pursuance of their beliefs. The practice, however, continues as 30 activists arrested and detained under the Duterte administration are still being charged with the same criminal offenses.

CARHRIHL is intended to correct the injustices done against political prisoners as far back as the Marcos Martial Law Dictatorship, including the nullification of repressive presidential decrees carried over to the succeeding administrations. With the signing of the Supplemental Guidelines for the full operation of the Joint Monitoring Committee (JMC) of CARHRIHL, there should no longer be any hindrance in the government’s commitment to adhere and fully implement the CARHRIHL. The JMC is the body tasked to administer the GPH-NDFP implementation of the CARHRIHL.

The JASIG—which is again operational after the Duterte government unilaterally terminated it in February 2017—also guarantees safety and immunity for the unhampered participation of NDFP personnel involved in the peace negotiations and “to avert any incident that may jeopardize the peace negotiations.”

The two agreements are more than enough legal bases for the Duterte government to release political prisoners and render justice and rectify their unlawful and unjust detention.

And while the prospects for a general amnesty proclamation still hang in the balance, the NDFP and its legal consultants are working for other modes of release of political prisoners, even if temporary such as in the cases of the peace talks consultants.