KA MAGGIE: ‘COMING OUT’ IN THE NPA

She practically spent her youth in the revolutionary movement, having been part of an activist organization in a Catholic high school at age 15. She is now 39 years old. She is a lesbian. The “awakening” happened at the same time she became conscious of the social issues affecting the country. That was in her elementary years.

“It helped that I always hear my parents discuss current events. Kaya elementary pa lang nakikipag-debate na ako, alam ko na noon yung US Bases (I could already engage in a debate on the US Bases when I was still in elementary),” Ka Maggie recalled. “At the time, I also had a crush on my female teacher,” she hastened to add.

For Ka Maggie, it wasn’t easy growing up with conservative parents who were both raised in the province. Also, between Ka Maggie and her parents was an age gap of 42 years. Hence, the burden of being a lesbian and activist was heavier— as both were widely considered by society as ‘aberration’, ‘abnormality’, even a crime.

‘Coming Out’ and ‘Going Up’

Like her ‘awakening’, ‘coming out’ and ‘going up’ (the mountain) to join the New People’s Army (NPA) happened at the same time. As she recounted her experiences it didn’t show that she went through a personal struggle as her sentences were often punctuated with laughter.

“Naging kloseta ako sa kilusan for a time kasi hindi ko alam kung ano’ng stand natin sa LGBT. Nakikiramdam muna ako (I kept mum about this in the movement because I didn’t know our stand on LGBT).” The way her high school collective handled the case of another lesbian member was an acid test.

“Nanligaw siya sa masa. E, di inulat ko dahil di pa panahon—bata pa kami, tapos masa pa niligawan. Pero, sa tingin ko, ang naging pokus ng usapan yung gender niya. So, ang sense ko ito pala yung handling ng kilusan sa gender (She courted someone who was unorganized so I reported it—we were still young and a masa was involved. But I felt the discussion focused on her gender, so I had a sense that this was how the movement handle cases such as this).”

Although she did not waiver on her commitment to the revolution, she decided “to stay in the closet.” At one point she even courted a male comrade; or opened herself up to courtship by other male comrades in her collective.

In college, she decided to finally ‘come out’ to her collective. Expecting ridicule, Ka Maggie sought integration with the NPA as soon as she ‘comes out’, “Kasi mas kaya kong harapin ang maririnig sa mga kasamang hukbo mula sa peasant kaysa sa mga YS na ‘to (I could stand comments from NPA peasant comrades rather from the youth and students),” she confessed. “For all my anxiety and insecurity, my collective’s reply was just ‘that’s it? Is there a problem?’, after which they immediately prepared me for my integration,” Ka Maggie recalled, as she laughed heartily.

It was during her integration when she decided to stay and join the people’s army. That was in 1998.

Lesbian Sisters

I was already in the NPA when Ka Maggie ‘came out’ to her parents. “Mas nauna akong nagsabi na maghuhukbo ako. Ang tingin ko kasi noon, too much na nga na ipatanggap na hukbo ako. E, NPA na nga, lesbiana pa. Sobrang bigat na para sa kanila (I first told them I was joining the NPA; admitting being a lesbian came later. I felt it would be too much for them to accept me as NPA and lesbian all at once).” It was only when she was getting married that Ka Maggie told her parents she is lesbian. “Babae, sabi ko. E, di lalong nagwala (I was marrying a woman I said and they really hit the roof),” she cringed.

At the start it was difficult for Ka Maggie to leave her parents specially because they were already old and ailing. “Bunso ako. Inisip ko kung di man ako magtatapos mag-aral, tiyakin ko na lang ako ang aalalay sa kanila (I was the youngest and since I don’t intend to finish school at least I would take care of them).” Back then, she still wanted to be a human rights lawyer.

Then she thought of her older sister, Ley. “Buti na lang, nung college napaugnayan ko ang kapatid ko. Na-organize din siyang hanggang ND (National Democrat) activist (It’s fortunate that I had my sister recruited and organized as ND activist while still in college).”

Though both sisters would discuss their involvement in the revolution, Ley admitted early on she wasn’t ready for Ka Maggie’s ‘level of sacrifice’. While Ley fully supported Ka Maggie’s decision, she reluctantly accepted the responsibility of taking care of their parents.

“Ang matindi kasi, hindi niya magawa ang gusto niyang buhay. Eh, lesbian din siya. Ako yung unang nag-out tapos umalis pa ako (My sister could not do what she wants. She’s a lesbian too. But I came out ahead of her and left for the mountains).”

“Ano ba ‘yan di ko magawa ang gusto ko dahil dyan sa decision mo (I can’t do what I want because of your decision),” Ka Maggie remembered her sister’s words. Both of them talked about their sexual orientation when they were in high school. But Ley chose to stay ‘in the closet’ and was at times forced to conform to the expectations of their parents, “but not as far as going into relationship with males,” Ka Maggie recalled.

Having a collective and a liberating consciousness facilitated Ka Maggie’s ‘coming out’. “Kung wala ang collective, wala ang kamulatan maghihintay ka na lang na mamamatay ang magulang mo bago ‘mag-out’. Dati yun ang naisip ko. Mas ang kapatid ko ang naging ganun, hintayin ko na lang. Nag-out naman siya bago namatay ang tatay namin (If it were not for my collective and awareness I would have waited for my parents to pass away before I can even ‘come out’. My sister had been forced with that choice, though she came out before my father died).”

Lesbians in the NPA

“I was the first lesbian in our unit. So I knew we were all adjusting at the start,” Ka Maggie mentioned. “Dumaan kaming lahat sa pag-aaral kung paano. Lalo na nung may ikinasal na (We underwent studies to understand each other, especially when a same-sex marriage happened).” But, she didn’t experience discrimination because of her gender preference. “Mas sa pagiging babae pa. Yung nag-excel ka sa pagsusuring pang-militar na supposedly pang lalaki. Pero once lang yun. At di yun pinalalampas ng collective (I exprienced it once, but it was more of my being a woman who excelled in military science which is deemed as the expertise of men. But my collective did not let that slide).”

Also, she was considered a ‘competitor’ by male comrades when it came to relationships. “Uunawain ko na lang yun na dahil mas maraming lalaki kaysa sa babae. E, syempre yung mga kasamang lalaki ang tingin iilan na nga lang kayo tapos kayo-kayo pa (I can understand that as there are more men than women in the NPA, and choices for men become limited as women court women),” she explained.

She’s never had a problem with lesbian relationships in the Party and in the people’s army. “Failed relationships”, said Ka Maggie can be attributed to “difference in perspective”—in staying or leaving the people’s army and in parenting—and never to gender preference.

A divorce ended her marriage. But what struck her, though, in that marriage was when, as a newly-wed couple, her collective asked them about their plan, “O anong plano niyo sa pag-aanak, para mapaghandaan, para mapagplanuhan (Do you have plans to bear children? We have to prepare for that. We need to have plans).” Up to now, she is still amazed at her group’s openness to include artificial insemination, and not just adoption, as option for her and her partner.

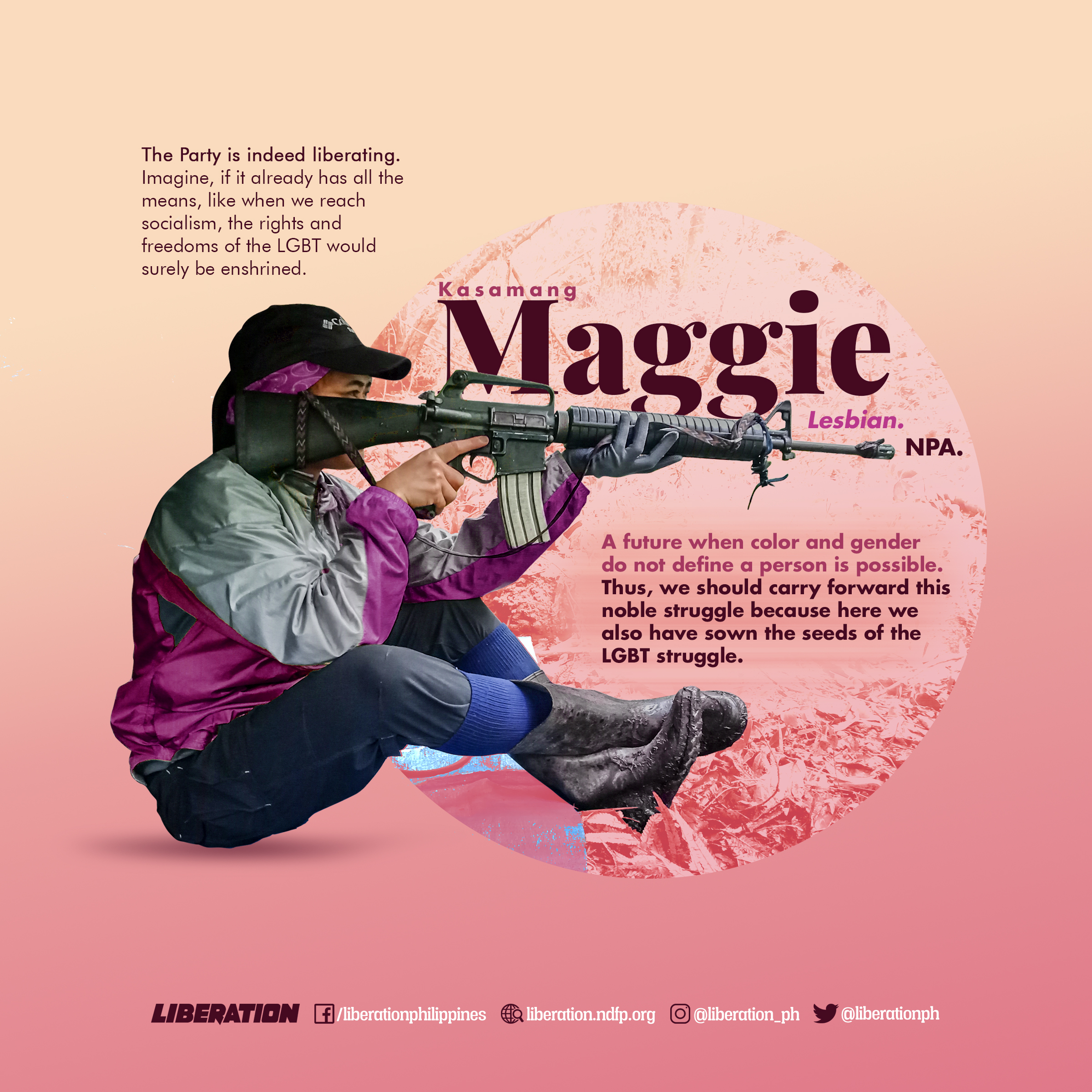

“Isang dahilan yan kung bakit proud ako sa Party, talagang mapagpalaya. Imagine, kung may means pa ang Party, lalo na kung Sosyalismo na, mas yayabong talaga ang kalayaan at karapatan ng LGBT (That is one of the reasons why I am proud of the Party; it is indeed liberating. Imagine, if it already has all the means, like when we reach socialism, the rights and freedoms of the LGBT would surely be enshrined),” she added.

Albeit recognizing the need for further intra-Party discussions and education sessions on the LGBT question, Ka Maggie is certain that the CPP has the leadership to advance the cause of the LGBT.

“Posible talaga ang panahon na ang bawat isa ay hindi na tumitingin sa kung ano ang kulay, kasarian. Kaya dapat ipagpatuloy natin ang dakilang pakikibakang ito dahil do’n din nakasalalay ang mga butil ng pakikibaka ng mga LGBT.”

A future when color and gender do not define a person is possible. Thus, we should carry forward this noble struggle because here we also have sown the seeds of the LGBT struggle.