Justice is the Heart of the Revolution

by Pat Gambao

The reactionary government’s rotten justice system has never been so outrageously unmasked as it is now through the Duterte regime’s blatant travesty.

In Duterte’s controversial “war on drugs”, self-confessed and publicly known drug lords get away unscarred while thousands of petty pushers and users, mostly from the poor communities, are summarily executed. In the plunder cases before the Ombudsman involving pork barrel, the regime’s department of justice is plotting to transform the most guilty scammer into a state witness.

Chief Justice Sereno’s impeachment case exemplifies the crude and desperate way of weeding out perceived obstacles to controlling the judiciary, in Duterte’s bid to monopolize power. Twist the laws, disregard the check-and-balance dictum, and get some stupid, ambitious, hopefuls into the plot.

Vilify, force to resign officials (they succeeded with Comelec Chair Andres Bautista) or file a quo warranto case, for good measure. Many retired military officers complicit in human rights violations, such as enforced disappearances, now occupy high positions in the bureaucracy.

The rotten judicial system

Ka Tato, a lawyer from the Lupon ng mga Manananggol para sa Bayan (Lumaban), an affiliate organization of the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP), described the government’s dispensation of justice as muddled, snail-paced, and biased towards the authorities. “This is not surprising because the court is among the instruments of coercion of the ruling class aimed to perpetuate the status quo,” he explained.

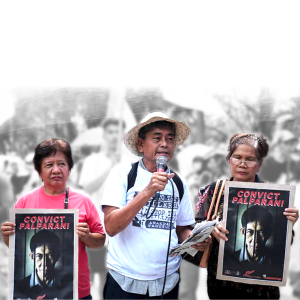

He cited Maj. Gen. Jovito Palparan, Jr., charged and tried for the kidnapping and disappearance of UP students Karen Empeño and Sherlyn Cadapan and peasant Manuel Merino, as “so far the highest-ranking military official to be criminally indicted for human rights violations in recent history.” However, Palparan enjoys the privilege of being detained in the headquarters of the Philippine Army, to which he belonged, rather than in a regular jail.

Liga ng mga Manananggol para sa Bayan (LUMABAN)

The trial of Palparan and his co-accused, Col. Felipe Anotado, M/Sgt. Rizal Hilario and Staff Sergeant Edgardo Osorio, has dragged on for seven years due to various dilatory tactics of their defense lawyers. The crime happened more than a decade ago, but the trial was concluded on February 15, 2018. How long it will it take for the court to promulgate its ruling?

The revolutionary justice system

“The main difference between the justice system of the revolutionary movement and that of the reactionary government lies in each one’s standpoint and viewpoint,” Ka Tato pointed out. The NDFP program, he said, embodies the people’s fundamental rights and freedom and takes into consideration the following: 1) the relations between the broad masses and the exploiting class; 2) the relations among party members; 3) the relations among the masses; and 4) the interests of the sectors. Following are his elaboration on these points:

The People’s Democratic Revolution seeks the social and national liberation of the masses long locked in the yoke of exploitation. Its judicial system thus takes the side of the exploited at all times against the interests of the exploiters.

Friendly relationships among the toiling masses and the progressive forces are ensured by resolving any dispute among them amicably. The interests of every sector are given prime consideration over the interests of the ruling classes.

The revolutionary movement has developed standards for the legal and judicial system at different levels and degrees. These are still being codified according to issues and sectoral interests towards crafting a comprehensive code. The three points of attention and eight basic rules of the New People’s Army (NPA) remain as the standards for military discipline. There are also rules and guidelines for agrarian reform, children’s rights, relationship between sexes, treatment of prisoners of war (POW), rules on the investigation and prosecution of suspected enemy spies, among others.

The revolutionary forces adhered to human rights and the principles of international humanitarian law in the course of the armed conflict even prior to the signing of the 1998 Comprehensive Agreement on Respect for Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law (CARHRIHL), the first substantive agenda in the peace negotiations between the Government of the Republic of the Philippines (GRP) and the NDFP. The NDFP also crafted a Unilateral Declaration of Undertaking to Adhere to the Geneva Conventions and Protocol 1.

All these laws, rules and guides are being observed in the guerrilla fronts by the organs of political power, which create committees or entities to implement them. These are aimed to establish order and dispense justice in the interest, protection, and defense of the masses.

Ka Tato cited the following example:

In March 1999 when the NPA released prisoners of war (POW) AFP Brig. Gen. Victor Obillo, Captain Eduardo Montealto, PNP Major Roberto Bernal and AFP Sergeant Alipio Lozada, the NDFP took the high moral ground as basis—humanitarian grounds and grant of clemency on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the founding of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and the NPA. It responded positively to the widespread appeals of well-meaning parties and personages such as Archbishop Fernando R. Capalla, Bishop Wilfredo D. Manlapaz, Msgr. Mario Valle, Atty. Jesus Dureza and Rev. Fr. Pedro Lamata, who composed the Humanitarian Mission; Senator Loren Legarda in a parallel personal initiative; Howard Q. Dee, Chair of the GRP Negotiating Panel; Archbishop Oscar V. Cruz, President of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines; Mrs. Obillo and Mrs. Montealto.

The NDFP negotiating panel ordered the release of the military officers in accordance with the authority vested on it by the NDFP National Executive Committee and the laws and and processes of the people’s democratic government (PDG), and in compliance with the CARHRIHL and the NDFP Unilateral Declaration of Undertaking to Apply the Geneva Conventions and Protocol 1.

Observing the Guidelines and Procedure for the safe release of POW, the NPA custodial force turned over the captives to their immediate families through the International Committee of the Red Cross and the Humanitarian Mission, Senator Legarda, and in the presence of some government officials, human rights advocates, and church people.

Punishing a ferocious enemy of the people

The execution of Bernabe “Bantito” Abanilla in February 2016 by the Front Operations Command of the NPA in the provinces of Cotabato and Bukidnon was the punishment for his involvement in the killing of Italian priest Fausto “Pops” Tenorio and former student journalist Benjaline Hernandez, as well as many human rights activists and indigenous peoples who resisted militarization in their ancestral domains. Abanilla was a member of the Citizen’s Armed Forces Geographical Unit (CAFGU) and the “Bagani Force” paramilitary group in Arakan, North Cotabato.

In October 2011, Tentorio was shot several times inside a parish compound in Arakan Valley, Cotabato. Four years later, a Special Investigating Team for Unsolved Cases found circumstantial evidence against the Bagani Group. Meanwhile, eight years after Hernandez was attacked by the CAFGU and military in April 2002, in Sitio Bukatol, Barangay Kinayawan, Arakan, the UN Committee, where a complaint of the killing was filed, found the government guilty for violating Hernandez’s human rights. Despite these findings, Abanilla continued to enjoy a wicked life in liberty until revolutionary justice finally caught up with him.

The revolutionary movement’s people’s court

In the Guide to the Establishment of the People’s Democratic Government, the justice system is envisioned to have a Supreme People’s Court as the highest judicial authority. It may also create special courts if the situation requires. The Hukumang Bayan (people’s court) is created by the people’s government at the provincial, district, municipal and barrio levels. In small and simple cases, the board of judges is composed of three, while in big and complicated cases, especially if death is the imposable penalty, the board is composed of at least nine judges. Judges are chosen based on merit.

The complaints should be detailed and the preliminary investigations thorough before the trial. The people’s court will study the sides of both plaintiff and defendant. Both sides shall be given sufficient time to be heard and can have a lawyer to present witnesses and evidence.

Usually hearings are done in public and any citizen is free to give his/her opinion regarding the case. If necessary, the people’s court will request the help of the concerned organ of the PDG to provide insights on the issues confronting the court.

The decision in every case shall be voted upon by the judges. Each judge shall explain before the board his/her vote. Usually, the decision on the case needs a simple majority vote of the board. However, in the case where death is the sentence, the vote should be a clear 2/3 majority. All the decisions shall be read and explained by the presiding judge.

The decision of the lower people’s court may be appealed to a higher people’s court. However, the people’s court may accept a motion for reconsideration of its decision. In cases where death is the sentence, these will automatically be appealed to the highest political and judicial authority of the region and automatically filed with the People’s Supreme Court or the standing organ responsible for it.

The people’s court on the ground

At this stage of the people’s democratic revolution, people’s courts are established in the guerrilla fronts. They commonly cover petty crimes and domestic concerns. Should the situation permit, hearings are done in public.

Arbitration is done by the NPA with local residents to strike a balance in the evaluation of the case. Members of the people’s court are chosen based on merit. They should be disinterested parties and not related to the defendants. The people’s court is usually composed of nine people. The defense also should undertake careful investigation to ensure that the rights of the defendant are protected. The case undergoes hearings, sentencing, and appeal, as the case may be. The Party section of the NPA is responsible for taking charge of the trial. The Executive Committee of the Regional Committee acts as the review board.

In the case of enemy spies, any tip will be carefully verified before the arrest and trial. Certain political conditions are considered such as the gravity of the offense, the age (minor) and the relationship of the offender with revolutionary forces. Death sentence is the last resort after one is proven guilty beyond reasonable doubt.

Contrary to the claims of its detractors, the NDFP judicial system is no “kangaroo court” because it follows a judicious procedure: investigation, indictment, hearings, sentencing, pardon, and release.

People in the barrios and even the local barangay councils acknowledge that revolutionary justice system is fair, simple, and swift.