A Woman’s Story: How the Revolution Set Her Free

by Vida Gracias

She froze. She felt numbed all over her body. That’s how Selya instantly reacted when she learned that her daughter, Mina, had been killed. It was in the late nineties.

“Kubkob,” Selya was told about the incident that cost her daughter’s life. But those who brought the sad news to her, Mina’s friends, tried to assuage her shock by telling her Mina was unarmed, that she was not a member of the New People’s Army (NPA). She was just with a group on an “exposure-integration” stint among the masses in that hinterland area when the incident happened, they said.

But why were guns trained on Mina and her companions, then fired—leaving some of them dead and others wounded? How many bullets shatter Mina’s face? Selya’s heart ached to its pith as she asked: “Ano’ng nangyari sa anak ko? (What happened to my kid?)” Mina was just 22, beautiful, a student leader, and a damn good writer.

A mother lost her daughter

Selya never really had a direct hand in Mina’s upbringing, as the latter grew up away from her maternal watch. Of her four children, Mina was the eldest. Though her husband came from a middle-class family he was not a good provider. The couple had to grapple with financial difficulties such that they could not afford to give their children proper education. Mina’s aunt came to the rescue; she took her under her care and sent her to school.

The pain in Selya’s heart persisted. She wanted to know fully what happened to her daughter, and why?

She remembered getting a call from Mina telling her, “Magpu-fulltime na ako” (I am going fulltime!)” What was that about? Selya didn’t even understand what “fulltime” meant. Later she learned that Mina was being restricted by her in-laws, slapped a few times, and placed under “house arrest.” But Mina persisted in what she had committed to pursue, and found a way to leave the house. Mina said she was going on a one-week case study of Dolefil Philippines, a pineapple plantation, in South Cotabato.

The last time Selya saw Mina was when she came for a short visit, slept in their house, and bonded with her siblings. Selya noticed that Mina had lost weight and had insect bites on her skin. Her stories hinted of her carrying five kilos of rice on her back and learning how to fire a gun. “Nagduda na ako (I became suspicious),” Selya quipped.

Selya went along with Mina’s friends to identify her body at a funeral parlor. “Sa paa pa lang alam ko na (Merely by seeing her feet, I knew it’s her),” said the mother who didn’t need to see the whole body to claim it’s her daughter’s.

Then one by one, people started coming to the wake, sometimes in groups aboard jeeps or trucks. They all came to honor her daughter. Priests, nuns, students, farmers, workers, people from all walks of life. Night after night they shared snippets of stories about Mina. And they were always singing of struggles and of hope. It was through their narratives that Selya came to know more about her daughter’s activities, her aspirations, and her deep commitment to serve the people.

It no longer mattered to her that Mina was being tagged as a member of the NPA.

Political awakening

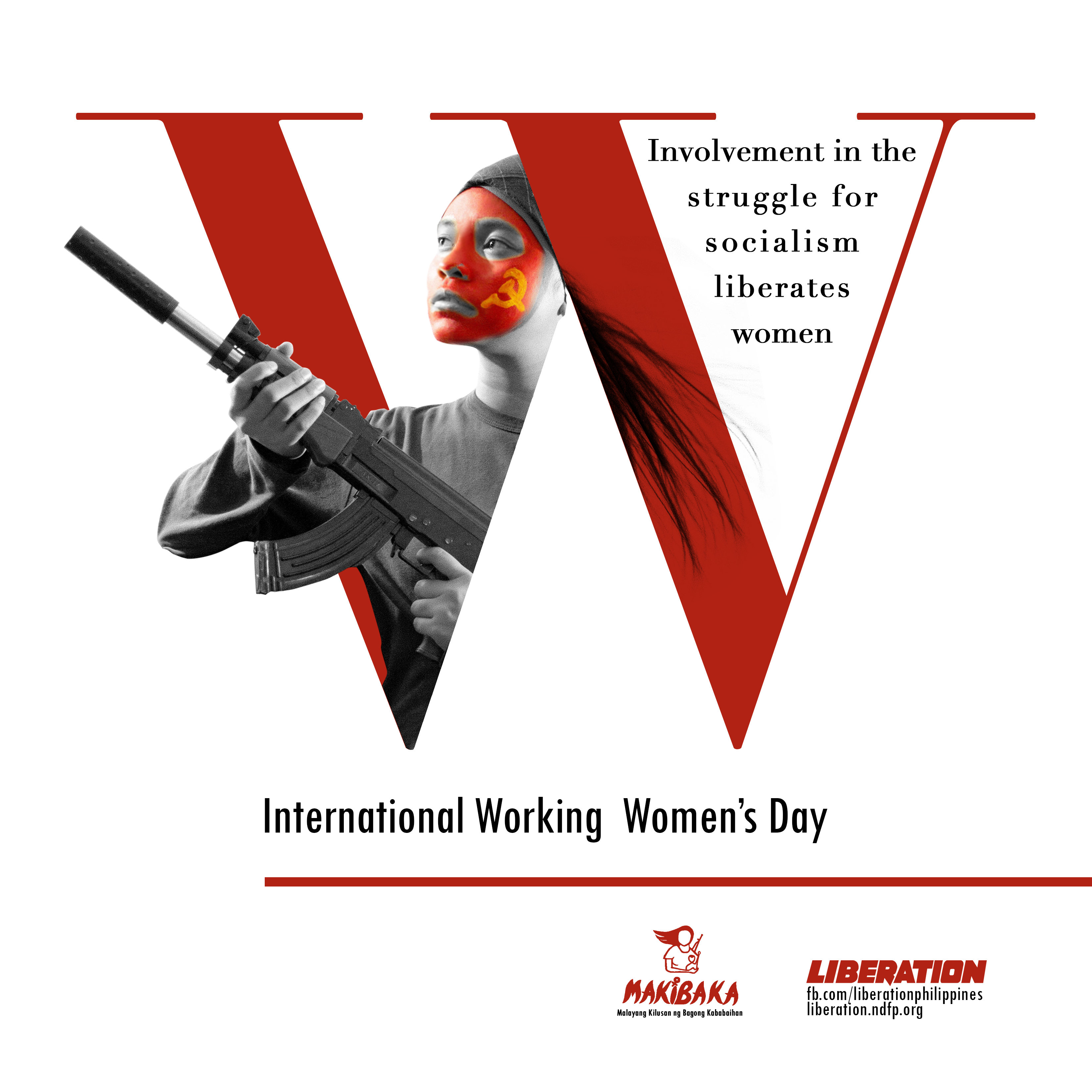

Years later it was Selya herself who was holding a gun. This mother in her fifties took the road that less mothers would have traveled, not just for her daughter’s memorial but for all that she had stood for.

Selya felt her bond with Mina becoming closer in her death than in her life. Her love and respect for Mina grew by leaps and bounds. Along with these came Selya’s political awakening.

For five years she fought for justice; she went trooping with other mothers and relatives of human rights violations victims to government agencies, demanding state accountability. The defendants in the case of her daughter’s killing were able to post bail on charges for multiple murders—and later were acquitted. She went to almost every rally, every fact-finding mission, and every forum to speak about her daughter’s case and those of other victims of human rights violations.

Selya also learned about a lot of things. Having come from humble beginnings, she knew first-hand what poverty was like. But she came to know that poverty was not a matter of fate but a consequence of social and economic inequality, oppression and exploitation by the few ruling classes over the majority over whom they rule. Participating in discussions and forums gave her the knowledge about the class nature of Philippine society. She was convinced about the need for a national democratic revolution to bring about fundamental changes that her daughter Mina and countless others selflessly fought for.

Revolutionary education struck deep. Unknown to many, Selya was a battered housewife. For years she was abused by her husband in more ways than one. She accepted her fate in quiet perseverance. After all she was a devout Christian who as a wife had been made to understand that she must submit to her husband’s authority.

As her political consciousness grew deeper and broader, she gradually developed her resolve to break free. Finally, one day she said enough was enough and separated from her husband.

Liberation

It was an act of liberation that her remaining children, in their late teens and early twenties, understood and approved of. But they cried when she told them she was leaving for Mindanao to spend six months in the guerrilla zone. Perhaps they cried even more when she did not return and decided to go “fulltime.” On the seventh month of her stint at the guerrilla zone she officially joined the New People’s Army.

“Tama siya. Walang mali sa ginawa niya (She was correct. There was nothing wrong with what she had done),” Selya declared about Mina. Her own experience in the countryside made her fully understand the choice that Mina had made before her. She put to rest all her questions about Mina’s choices that led to her martyrdom at such a young age.

Meanwhile, Selya became an inspiration to her younger comrades. She did not ask for any special treatment, although she was in her fifties. She would do her tasks just like the rest, carrying her own load in long treks and participating in military trainings.

Trusting in her maturity, she was asked to take charge of the NPA prisoners of war (POWs) while in protective custody of her unit, specially a town mayor who was awaiting trial before a people’s court. She would see to the POW’s daily medical check-up and engage him in discussions about the NDF’s 12-point program. Later, after the mayor admitted his sins and asked for forgiveness, he was set free and became an ally of the movement.

“Pag ando’n ka, wala ka nang hahanapin pa (Once you are there, there’s nothing more you would wish for)” was how Selya defined her life in the countryside under the governance of the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP). For sure there are material comforts not available in the guerrilla zones; there are ever-lurking threats of military attacks, but it is here in the ranks of the revolution where ordinary folks become whole and enjoy their newfound freedoms.

And so it is with Selya. With eyes sparkling, she speaks of having found a new love in her life with a comrade in arms. And her children respect her right to such new love. “Pinalaya ko na ang aking sarili (I have liberated myself),” declared Selya. And her comrades are only too happy to see her smiling so sweetly.