FAILING OPLANS: from Marcos to Duterte

Since 1981, when the Marcos dictatorship initiated Operational Plan (Oplan) Katatagan purportedly “to defend the state” (the besieged fascist regime) from the fast-growing New People’s Army (NPA), each succeeding administration has followed suit. This is understandable, since the planner-implementor of every Oplan has been the same military establishment habituated to martial-rule repressive action.The Oplans have had varying names. Yet all have been aimed at deterring the growth of or strategically defeating the NPA, to preserve the existing rotten ruling system.These were: Corazon C. Aquino’s Oplan Mamamayan and Oplan Lambat-Bitag I and II; Fidel Ramos’ Lambat-Bitag III and IV, and Oplans Makabayan and Balangay (which transitted into Joseph Estrada’s truncated presidency); Gloria Arroyo’s Oplan Bantay Laya I and II; Benigno Aquino III’s Oplan Bayanihan; and Rodrigo Duterte’s Oplan Kapayapaan and Oplan Kapanatagan.While each succeeding administration adopted its predecessor’s operational concepts, it added new ones. But all such operational concepts were, invariably, copied from the counterinsurgency guide of the US Army. Although these may have worked for some time in America’s wars of aggression and intervention in different parts of the world, over the long run they have failed to achieve their prime objective: decisive military victory.Instead, these American wars—practically wars against the peoples of the countries they invaded, starting with the Philippines at the turn of the 20th century—have left behind countless deaths mostly of civilians, including children; pervasive human rights violations; displacements en masse of the population; and massive destruction of socio-economic resources requiring decades to recover.Similarly, albeit in smaller scale, these have been the dire impacts of the successive counterinsurgency Oplans on our people—since Marcos’ time to the present—in the undefined arenas of war across the archipelago, mostly in the countrysides and hinterlands.The current Oplan Kapanatagan started as Oplan Kapayapaan in January 2017. The latter was also dubbed as the AFP Development Support and Security Plan 2017-2022, which the Armed Forces off the Philippines (AFP) described as an advance from Aquino III’s Oplan Bayanihan. It adopted the latter’s “whole-of-nation” or “people-centered” approach. Oplan Bayanihan, the AFP bragged, resulted in getting 71 of the 76 (out of 86) provinces deemed to be “insurgency affected” declared as “insurgency free” and “peaceful and ready for further development.”The change to Kapanatagan stemmed from the AFP’s assessment that Oplan Kapayapaan was failing to achieve its targeted goal to defeat the NPA midway of Duterte’s six-year term of office.When first announced by AFP chief Gen. Benjamin Madrigal before the May 2019 midterm elections, it was billed as the AFP-PNP Joint Campaign Plan “Kapanatagan” 2018-2022. Madrigal described it as a “medium-term broad plan that shall guide the AFP and Philippine National Police (PNP) in providing guidelines and delineation of authority while performing their mandated tasks to promote peace, ensure security, and support the overall development initiatives of the government towards inclusive growth.” It is anchored, he added, on the national strategic guidance defined in the National Vision, National Security Policy, Philippine Development Plan, National Peace and Development Agenda, and the 2018 Department of National Defence (DND) Guidance and Policy Thrusts.“The respective strategic thrusts of the AFP and PNP were thus harmonized in this Joint Campaign Plan “Kapanatagan” 2018-2022,” Madrigal said. He called it “a dynamic process to establish greater inter-operability in our continuing operations to address security concerns within our respective areas of concern, including all other productive endeavors wherein we join hands in support of national government initiatives as envisioned by President Rodrigo R. Duterte.”Specifically, Madrigal cited two “salient features” of Campaign Plan Kapanatagan: 1) The PNP shall support the AFP in combat operations involving the suppression of insurgency and other serious threats to national security; and 2) The PNP shall take the lead role in law-enforcement operations against criminal syndicates and private armed groups, with the active support of the AFP.”It was in the Cordillera region where the AFP and PNP first “rolled out” Oplan Kapanatagan, after the May midterm elections. Northern Luzon Command (Nolcom) chief Lt. Gen. Emmanuel Salamat then said: “Because of the effort of the AFP and PNP in preventing violence and any actions of the local terrorist groups in the Cordillera region, we assure that the AFP and PNP will continue to work together through Joint Kapanatagan Cordillera.”He emphasized that the AFP-PNP would carry out “joint actions and plans to ensure a more collaborative effort to address the peace and security concerns, especially in those geographic isolated areas” (the guerrilla zones) in Cordillera. He expressed hope that the local government units and other “partner agencies” would collaborate to ensure implementation of Executive Order 70 and the National Task Force to End the Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC) it created, headed by Duterte.Gen. Salamat disclosed that at a “national convergence” meeting in Malacañang, all those working under NTF-ELCAC had put all efforts “to come up with a cluster of responses” on the different issues, including “issues that have been exploited by the local terrorist groups” so that the government can respond to them.And how has the government responded through NTF-ELCAC and Oplan Kapanatagan?Recently, the Cordillera People’s Democratic Front (CPDF-National Democratic Front of the Philippines) issued a primer on this two-in-one counterinsurgency plan, titled “Disturbance and Plunder by the State Against the People.” Among others, it points out the following:R(egional)TF-ELCAC Cordillera was formed in July 2019, followed by P(rovincial)TF-ELCAC Mt. Province in September. In the last three months of the year municipal-and barangay-level TFs are targeted to be formed.In September, Nolcom launched military operations in various parts of the Cordillera and Ilocos regions, side-by-side with these joint campaigns by the AFP and PNP: disinfomation, surveillance, psychological war (disseminating false information that the NPA had planted land mines in the mountain areas of Bauko, Tadian, and Sagada towns in Mt. Province); forcible entry into civilian homes purportedly to “collect” firearms kept for the NPA in the communities of Besao town; threat and pressure used on residents summoned to pulong masa to sign up on a memorandum of agreement with the AFP-PNP and a declaration of the CPP-NPA as “persona non grata”; holding seminars and symposia on Duterte’s “war on drugs”; and delivery of “services”, “relief and rehabilitation”, among others.The AFP-PNP also set up detachments within three communities of Besao and one in Sagada, in violation of the Comprehensive Agreement on the Respect for Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law (CARHRIHL). (In the National Capital Region, through Implan/Oplan Kalasag, the NCR version of Oplan Katatagan, the AFP-PNP tandem has also set up detachments in some communities in Caloocan City. Uniformed armed teams engage in red-tagging, harassment, intimidation, while others offer “livelihood programs” to identified leaders and members of progressive organizations).CPDF also says the implementation of Oplan Katatagan and NTF-ELCAC in the region aims to facilitate the entry of energy and mining projects by foreign-local joint ventures that threaten the ecology, and violate the Cordillera people’s right to their ancestral lands. It named the following: Bimaka Renewable Energy Devt. Corp., Hydroelectric Dev’t Corp., Chico River Pump Irrigation Project by China’s CAMC Engineering, Aragorn Power Energy Corp., and Cordillera Exploration Co. Inc.-Nickel Asia of Japan.In sum, CPDF denounces the two-in-one campaign as designed to “pacify and press the people to obey the dictates of the reactionary state.” It calls on the Cordillera people to assert their rights, oppose the campaign through various means, and expose the true intent of the campaign: to crush the just struggle of the oppressed masses.It’s useful to note that, in 1981 the Marcos dictatorship already employed thru Oplan Katatagan the full force of the AFP, the police and paramilitary forces, its “development agencies”, and some civilian organizations. Duterte’s Oplan Kapanatagan and NTF-ELCAC—backed up by extended martial law in Mindanao and state of national emergency in other areas of the country—can be correctly described as an “Enhanced Oplan Katatagan.” Note further: the Oplan failed—in 1986 the people ousted Marcos.#FightTyranny

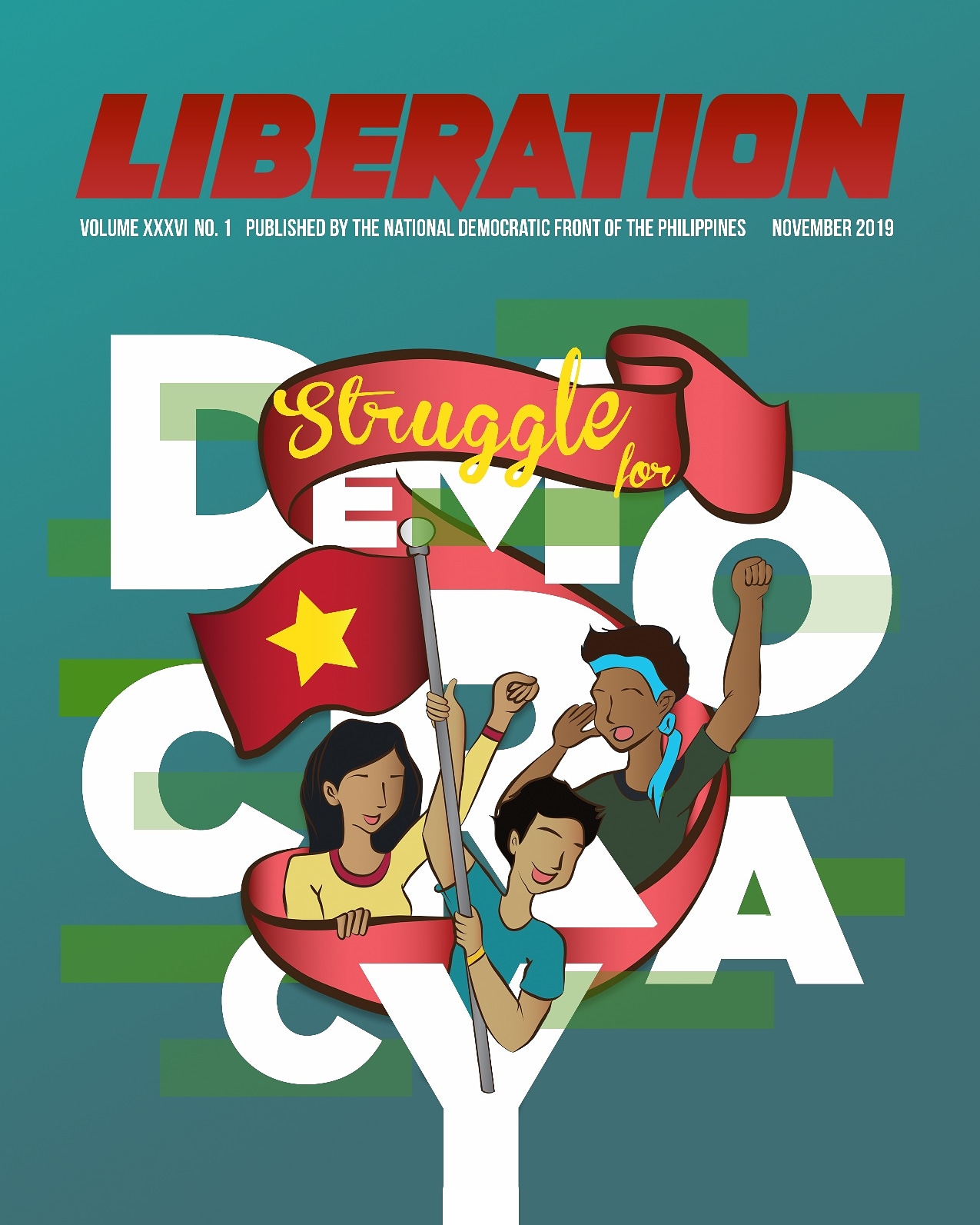

#StruggleForDemocracyDOWNLOAD LIBERATION NOVEMBER 2019 ISSUE:

https://drive.google.com/folderview?id=1-gzWR8-ZOqiK8RlJa0qS1klqWkgIEKUZ—–

VISIT and FOLLOW

Website: https://liberation.ndfp.info

Facebook: https://fb.com/liberationphilippines

Twitter: https://twitter.com/liberationph

Instagram: https://instagram.com/liberation_ph