Steeled by Decades of Struggle, the Negrenses Keep the Revolutionary Fire Ablaze

by Iliya Makalipay

Tears were shed copiously. There was mourning all around as the number of dead bodies in Negros Island continued to rise. And there was justified rage—because these were not mere numbers or bodies.

They were peasants, local government executives, educators, human rights defenders, lawyers. There was even a one-year-old baby. All of them were victims of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP), the Philippine National Police (PNP), and the Duterte Death Squads (DDS).

Stupid as it has shown up itself to be, the tyrannical regime wasted no time in accusing the New People’s Army (NPA) of killing those whom it had tagged as NPA members and sympathizers.

Peasant advocate groups have reported 87 killed from 2017 to mid-August 2019. Forty of the victims were mercilessly slain after Duterte’s Memorandum Circular 32 took effect on November 22, 2018: it ordered more troop deployments in Negros, in the Samar provinces, and in the Bicol region purportedly to “suppress lawless violence.” A month after, in consonance with Memo Circular 32, state security forces launched Oplan Sauron in Negros Island.

Currently, at least 11 regular and special battalions of the AFP and PNP operate in the island, supported by paramilitary groups such as the CAFGU (Civilian Armed Force Geographical Unit) and the RPA-ABB (Revolutionary Proletarian Army-Alex Boncayao Brigade). At the height of the killings in July-August 2019, the PNP deployed 300 more members of its Special Forces, further escalating the tension and the abuses.

To justify the massive deployment and brutal military campaign, Col. Benedict Arevalo admitted to media that what was initially passed off as tokhang (“drug war”) operations were actually counterinsurgency actions.

The AFP assumes that the central part of Negros, where most of the killings happened, is used by the NPA as “highway” to easily reach both sides of Negros Island—Occidental and Oriental.

“The rebels are trying to create a base somewhere in the boundaries because it’s very important for them to connect and control both islands. It’s like grabbing Negros by the neck,” a news report quoted Arevalo, commanding officer of the 303rd Infantry Brigade-Philippine Army.

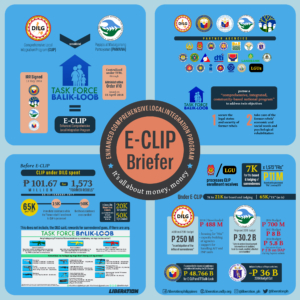

In July 30, the Provincial Task Force to end local communist armed conflict was formed in Negros Oriental following Malacanang’s issuance of Executive Order 70, which created the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC), headed by President Duterte himself. The move is part of the “whole-of-nation approach” the regime is using to create public perception that its counterinsurgency operations involve the participation of the entire government, civil society, and the civilian population.

Still and all, the victims of these police and military operations in Negros were unarmed civilians.

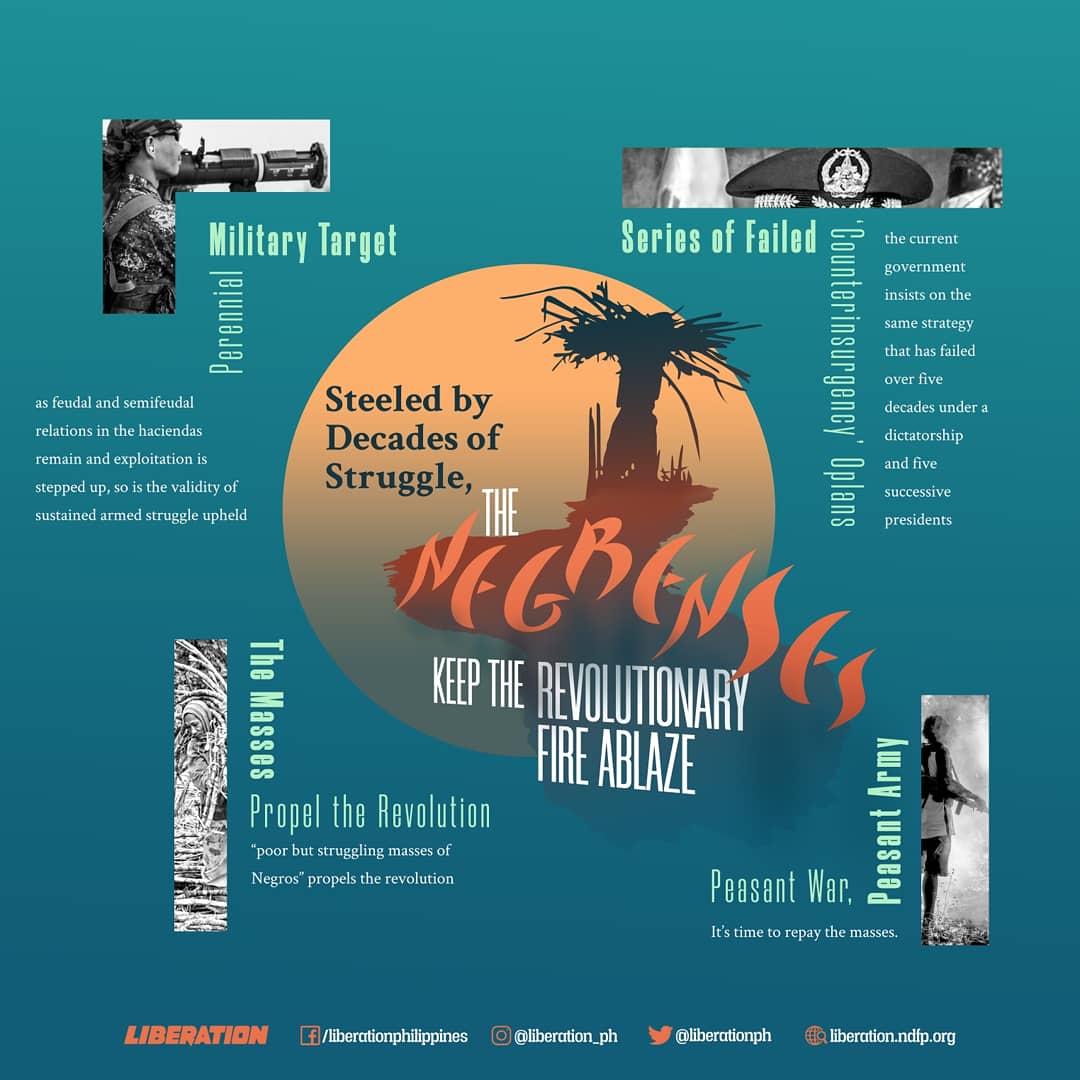

PERENNIAL MILITARY TARGET

This is not the first time state forces deployed hundreds of troops in the island— intended to decimate the NPA and “wipe out” its revolutionary base there. In fact, every president—from Marcos to Duterte—has invariably aimed, by the end of his/her term, to defeat the New People’s Army and destroy its revolutionary mass base.

During the Marcos dictatorship, Negros was depicted as a “social volcano” waiting to explode. Almost 40 years later, it has remained so because there was never any palpable change in the economic system and the deplorable lives of the poor people. As feudal and semifeudal relations in the haciendas remain and exploitation is stepped up, so is the validity of sustained armed struggle upheld.

In the last few months of the dictatorship, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) pointed out Marcos’s inability to address the sugar crisis and its consequent labor unrest and the military’s failure to contain the rebellion that has swept the island because of extreme poverty. The CIA report, dated May 1985, had been declassified and sanitized and was approved for release in 2011.

The report said: “We judge that later this year (1985), Negros may become, after Mindanao, the second politically important island in the archipelago where Communist control rivals that of the government.”

It added: “Despite the trouble looming on Negros, President Marcos shows no inclination to improve the counterinsurgency effort by bolstering the military or dismantling the sugar-marketing empire of his political ally, Roberto Benedicto. … Government efforts that are taken to ease the plight of the sugar workers are largely cosmetic.”

The “fall of Negros”, the report concluded, “would provide an important psychological defeat for the government and further depress morale in the armed forces. It would also confirm to the Communist Party that its long-term strategy is on the mark.”

Now under the sixth post-Marcos president, feudal relations, the centuries-old hacienda system, landlessness, and agrarian unrest are still prevalent. Adding to these social and economic ills are large-scale mining companies that prey on the island’s mineral resources and degrade its environment.

More than half of the country’s sugar mill and plantation workers are in Negros, earning an average daily income of Php 50-67, a far cry from the mandated minimum wage of Php 300. The glaring reality is farmers go hungry every day, both before and after the much-dreaded tiempo muerto, the idle period between sugarcane harvests.

There is widespread landlessness despite the so-called agrarian reform programs implemented by past administrations. Negros has still at least 600,000 hectares of lands that have escaped distribution under the largely-failed Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP) started by the Cory Aquino government in 1988.

Continued exploitation and oppression and non-implementation of genuine agrarian reform and rural development have been surefire stimuli for resistance—both armed and unarmed. It is for this reason that all attempts by the successive governments to defeat the revolutionary forces have ended in failure.

The Philippine government may have somehow identified the causes of the protracted armed conflict, but it has persistently pursued the wrong solution—the militarist solution of trying to eradicate the symptom—instead of seeking to resolve the root causes.

SERIES OF FAILED ‘COUNTERINSURGENCY’ OPLANS

Interviews with several villagers in Negros Oriental revealed two military operational plans (Oplans) etched deeply in their collective memory: Oplan Thunderbolt under the Cory Aquino regime and Oplan Bantay Laya of Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. Decades from now, they would remember too the brutality of the military operations under the Duterte regime’s Oplan Kapayapaan/Kapanatagan.

Despite or because of martial law, Marcos failed. And what the Marcos dictatorship failed to attain, the succeeding “restoration-of-democracy” government of Cory Aquino tried to finish—by using the very same corrupt and abusive state security forces that Marcos had fully harnessed and coddled.

As Cory Aquino wielded her “sword of war” through Oplan Lambat-Bitag I and II, Negros became a “pilot area”. A fact-finding report in 1988, titled “Mountain Tempest”, quoted the government as claiming that “the deployment of more troops and the use of more sophisticated weapons…can wipe out insurgency by 1992.” Essentially, Cory Aquino’s counterinsurgency program was derived from America’s “low-intensity-conflict” strategy which, at the time, was also being implemented in Latin America, with incalculable consequences in terms of countless killings and massive-scale human rights violations.

Rev. Romeo Empestan, in his book “From the Struggles of the People and the Church of the Poor in Negros in the 70s to 90s,” recalled that there were four simultaneous localized Oplans implemented during this period: Thunderbolt, Kahilwayan (freedom), Habagat (south winds), and Amihan (north winds). Oplan Thunderbolt would become the most notorious of the four.

Oplan Thunderbolt resulted in more than 30,000 (some reports cited as high as 100,000) evacuees in seven relocation sites. Most of the evacuees were from the now-familiar town of Sta. Catalina and Guihulngan City, in Negros Oriental, where the spate of killings under Duterte is happening. The late outspoken and courageous Bishop of Bacolod City, Antonio Fortich, said the mass dislocation of civilians at the time was “the biggest evacuation in one place in the country since World War II.”

Aside from the regular companies of the Philippine Constabulary (PC), units of the Scout Rangers, Airborne, were used in the counterinsurgency campaigns, along with vigilante groups such as Pulahan (red), Ituman (black), Putian (white), Way Sapatos (literally, no shoes) and the notorious Alsa Masa (Rise up, masses) that arose in Davao City. Private armies of landlords, hiding under the cloak of Philippine Constabulary Forward Command (PCFC) were also employed in military operations.

Upland farmers in Sta. Catalina town recalled seeing tora-tora planes used in bombing their communities, forest areas, and rivers suspected as NPA encampments. Fr. Empestan also mentioned bombings using helicopter gunships, F5 jet fighters, and howitzers. The communities were eventually declared “no man’s land”, a common practice in those days where anyone on sight was shot at by soldiers. At least seven incidents of massacre were recorded. There were burning of houses and parish churches, arrests, ‘salvaging’ (a term used to refer to what is now known as extrajudicial killings), and disappearances.

In a September 1, 2018 statement, Juanito Magbanua, spokesperson of the Apolinario Gatmaitan Command of the NPA Regional Command, described the current military operations in Negros since early 2018 as reminiscent of Oplan Thunderbolt in the late 80’s—the evacuations, bombings, and the destruction of Negros’ virgin forests.

Cory Aquino’s term ended in 1992 with the revolutionary movement surviving the military assaults. Thus, her successor Fidel Ramos—also the engineer behind her two Oplans—only had to continue the same counterinsurgency program Oplan Lambat Bitag III and IV. Oplan Flush Out was its localized version in Negros. It was during Ramos’ term, however, when the government first recognized the need to combine a “non-militarist” solution to the armed conflict—the pursuance of the GRP-NDFP peace negotiations, which produced positive results.

A decade later, in 2008, a Negros version of Gloria Arroyo’s nationwide Oplan Bantay Laya (OBL) I and II, the Oplan Cut Wedge, attempted yet again to “cut/stop the ability of the NPA to hop from one island to another.” The objective was the same; the mode of military operation was similar.

At least four infantry battalions of the Philippine Army were deployed in Negros, plus a battalion of the Special Elite forces of the Scout Ranger, two division-level reconnaissance companies, plus two companies supervising more than 2,000 CAFGU paramilitary recruits. The fanatic groups such as Pulahan, Ituman, etc. were replaced by two platoons of RPA-ABB (Revolutionary Proletarian Army-Alex Buncayao Brigade). A breakaway group from the NPA in the 1990s, the RPA-ABB (Tabara-Paduano group) has morphed into a paramilitary group, recently “demobilized” but has vowed to fully cooperate with the Duterte regime. At the start, it posed itself as a revolutionary group.

Simultaneous deployment of military units in a community, akin to Oplan Sauron, was already employed during OBL’s implementation.

In Barangay Guihulngan for example, almost two battalions of Philippine Army were deployed. In another village, some 130 troops were stationed for six months, with a division-level reconnaissance unit on standby in a nearby town.

People were interrogated, threatened and charged with trumped-up cases, the latter as part of the “legal offensive” of the Arroyo regime against its perceived enemies. There was massive recruitment of people to join the Barangay Defense System (BDS). Parallel formations were created in an attempt to draw in those who were members of progressive organizations.

Arroyo’s OBL was patterned after the U.S. 2009 Counterinsurgency Guide that has formally included the “whole-of-nation, whole-of-people” strategy purportedly to complement combat operations. The “whole-of-nation” approach would become the thread in the subsequent Oplans up to the Duterte regime’s Oplan Kapayapaan (Peace)/ Kapanatagan (peace/tranquility).

A similar counterinsurgency operation was in place when B.S. Aquino III assumed the presidency in 2010. As it was still patterned after the US Guide, massive troop deployment was again employed in the island. The revolutionary forces counted up to 30 combat companies in Negros.

But while Aquino continued OBL, the regime highlighted the “shift” to “whole-of-nation” approach to conjure an image of a nation united to battle “insurgency”, even calling it Oplan Bayanihan (a collective endeavor Filipinos are known for) and complemented it with a task force composed of so-called civil society stakeholders.

Nada. What was fervently targeted has never been achieved by any of these Oplans. Obviously, every Oplan has only brought more killings and numerous human rights violations.

Still, the current government insists on the same strategy that has failed over five decades under a dictatorship and five successive presidents.

THE MASSES PROPEL THE REVOLUTION

The Philippine government chose to remain blind and deaf through time, ignoring the fact that the strength of the revolutionary forces in Negros, and elsewhere in the country, comes from the exploited and oppressed poor, especially the peasants and workers. It is their best interest that the national democratic revolution— the key democratic content of which is agrarian revolution— uppermost fights for.

It is thus not surprising that the “poor but struggling masses of Negros” propels the revolution.

The masses played a vital role in the recovery and rebuilding of the CPP and the NPA in Negros in the 1990s. “(They) did not allow us to give up and encouraged us to rebuild,” recalled Frank Fernandez, detained peace consultant of the National Democratic Front (NDFP). In an article published by Kodao productions on July 8, 2019, Fernandez recalled, “There was almost no NPA left in Negros in 1994.”

The reason was not because the government’s counterinsurgency’program suceeded but because of the internal weaknesses of the CPP-NPA leadership in the area at the time. Fernandez explained that the movement diverted from the correct line and strategy in the conduct of the people’s war.

(That period of disorientation resulted in the breakaway of former members and led to the formation of the RPA-ABB. In 2000 said group engaged in pseudo-peace talks and signed a peace agreement with the Estrada government in exchange for a hefty amount of money. It continued to deteriorate into a paramilitary group, having been involved in numerous cases of extrajudicial killings, victimizing farmers. It has recently signed another ‘peace agreement’ with the Duterte regime and got another Php 500 million purportedly for social services programs.)

Reaffirming the correct ideological, political and organizational line, the CPP-NPA in Negros has since then fully recovered, with the unstinting support of the masses.

As Frank Fernandez said, “It’s time to repay the masses”.

PEASANT WAR, PEASANT ARMY

Repaying the masses comes in three main forms—implementing agrarian revolution, establishing local organs of political power, and pushing forward the armed struggle.

Juanito Magbanua, the Apolinario Gatmaitan Command spokesperson, cited the successful 17 armed actions of the NPA in Negros in the first eight months of 2018 as proofs of the “NPA’s increasing capability in launching armed struggle that is integrated with agrarian revolution and base building.”

As early as 2016, the Pambansang Kalipunan ng mga Magsasaka (PKM or the National Federation of Peasants) revealed that the revolutionary movement in Negros and Central Visayas have confiscated some 2,000 hectares of land, which benefitted at least a thousand farmers. The confiscation and distribution of lands, mostly idle and abandoned, are part of the agrarian revolution being implemented by the NPA with the PKM.

Comprehensive military-politico training of red commanders and fighters were launched to improve their “fighting skill, political capability, combat discipline, and revolutionary militance,” according to Magbanua. Majority of the trainees were peasants while 15 percent came from the petty-bourgeoisie.

Recognizing the importance of Negros island in the overall development of people’s war, Magbanua said the armed revolutionary movement in Negros must “overcome its weaknesses and rectify its errors in order to help frustrate the US-Duterte regime’s Oplan Kapayapaan and contribute in the national development of the strategic defensive of the people’s war towards a new and higher stage.”

The last time the island command conducted a training was in 2008 when the AFP implemented Oplan Bantay Laya 2 and shortly after, Oplan Bayanihan.

“The people’s army in the island had to make do with politico-military crash courses in the face of sustained search-and-destroy operations of the enemy until 2013, while prioritizing rebuilding work of the revolutionary mass base thereafter,” Magbanua explained.

At the same time, he added, punitive actions against abusive state forces and criminal elements have been meted out.

In the last six months of 2018, the NPA punished 14 landgrabbers, criminal elements, and intelligence assets of the 303rd Brigade responsible for human rights abuses against peasants, including the killing of activists in the legal organizations. These punitive actions have reduced the AFP/PNP’s capability to “inflict further harm upon the people’s lives, rights, and livelihood within and outside the guerrilla areas in the island,” Magbanua said.

Meantime, Dionesio Magbuelas, spokesperson of the NPA Central Negros-Mt. Cansermon Command, reported that Red fighter burned down some 120 million-peso worth of heavy equipment owned by a mining company. The action, he said, was a punishment meted on the firm for the destruction it had caused on the environment and sources of the people’s livelihood in Ayungon, Negros Oriental.

At the height of the attacks against the masses in Negros, the CPP-NPA central leadership issued a call for the NPA to defend the people of Negros. Magbanua claimed the punitive actions were “long overdue” because killings of unarmed civilians continued to escalate.

The CPP has denounced the spate of killings and numerous human rights abuses against civilians as acts of cowardice. State security forces, it noted, turned their guns against unarmed civilians in retaliation and to cover up for their failure to eliminate the revolutionary forces in the region.

Tempered in fighting one armed counter-revolutionary campaign after another—from the Marcos-era martial rule, through Operation Thunderbolt, and the more recent Oplan Bayanihan that deployed at least 30 combat companies in the island—the NPA in Negros has vowed unwaveringly to defend the masses against the intensifying militarization and fascist attacks of the Duterte regime. ###

#PeasantMonth

#ServeThePeople

#JoinTheNPA

—–

VISIT and FOLLOW

Website: https://liberation.ndfp.info

Facebook: https://fb.com/liberationphilippines

Twitter: https://twitter.com/liberationph

Instagram: https://instagram.com/liberation_ph

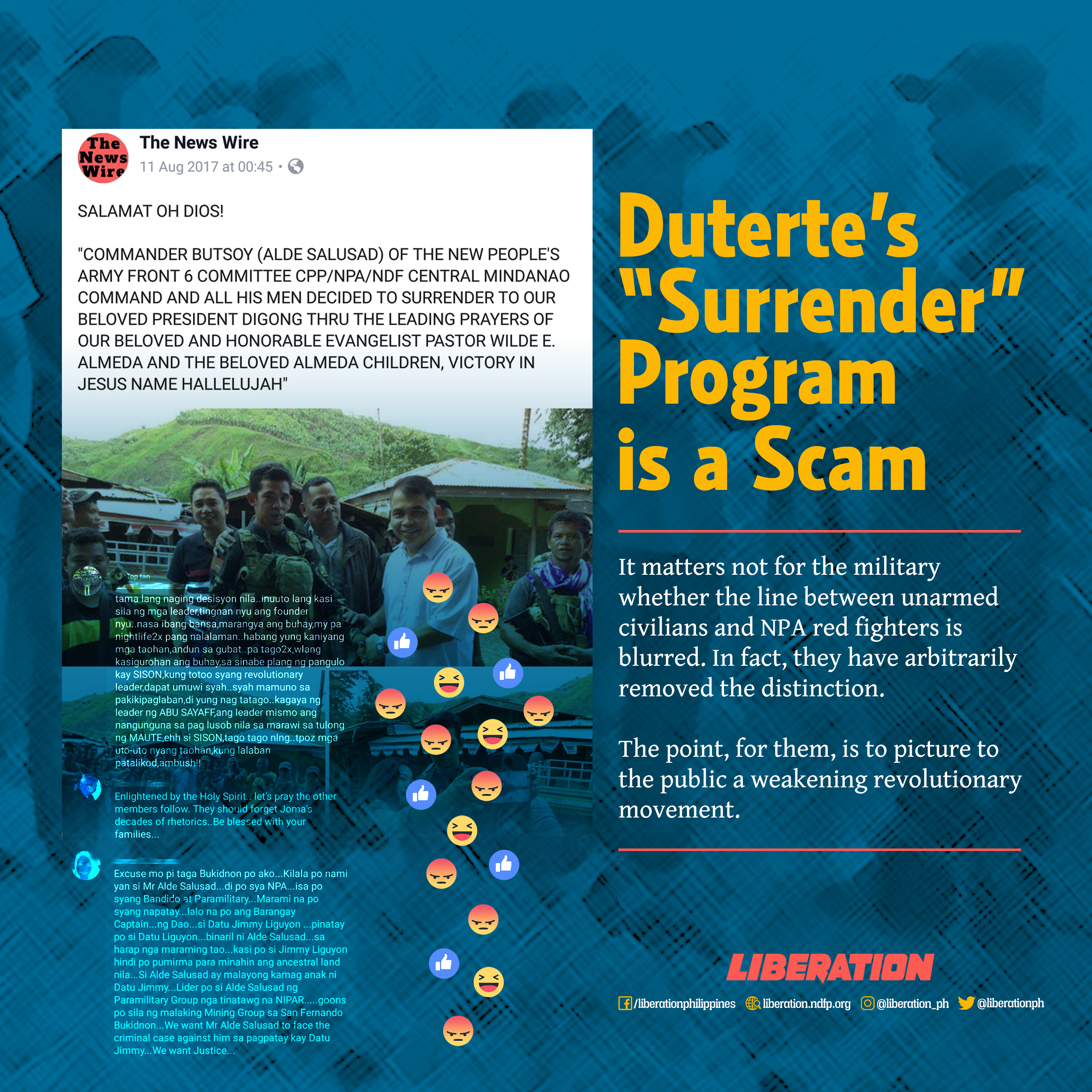

In August 11, 2017, five years after he killed Liguyon, Salusad was presented by the AFP as “NPA surrenderee” and was awarded Php100,000 in cash. Then in March 2018, the military included Salusad in the list of more than 600 names and aliases of alleged members of the CPP and the NPA in a petition for proscription filed at a Manila regional trial court.

In August 11, 2017, five years after he killed Liguyon, Salusad was presented by the AFP as “NPA surrenderee” and was awarded Php100,000 in cash. Then in March 2018, the military included Salusad in the list of more than 600 names and aliases of alleged members of the CPP and the NPA in a petition for proscription filed at a Manila regional trial court.