Manlalakbay sa Magdamag

ni Kas Jeff, Rodante Urtal Command [Isinalin nina Kasamang Tara, Kasamang Sara, Kasamang Ara]

Tiarabot na an uran.

Pangilal-an han mga bituon ha kalangitan.

Antes pausa-usa, pades-pades,

Parungpong hira nga manhitago

Ha luyo han panganuron han kagab-ihon.

Makikisirong kita nga mga manlalakbay

Ha buksol nga butkon hini nga bukid.

Nakapas-an ha maabtik niya nga sugbong

An mga hagtaas nga kahoy

Temporaryo nga sasab-ongan naton

Han aton mga duyan ngan pahuway.

Kakantahan han durungan nga koro

Han mga ngiya-ngiya, mananap ngan insekto,

Ha duyog han mga karasikas han mga dahon,

An agsob nga panuro han uran,

Ha haganas han sapa ha unhan

An pagal naton nga mga kalawasan.

Igtataklap naton an huram nga dagaw

Surusumpay hira nga hitaas ngan habubo,

Halapad ngan magnipis nga mga dahon ngan sanga.

Kamuplahe an kasusudkan hini nga kagugub-an

An magtatago han aton mga tiagi nga nahibilin.

Pero ayaw pagsayop hin hilarum nga pangaturog

Ha tikahilarum nga ritmo han katutnga nga kagab-ihon:

Ini an pahinumdom han kahigaraan han kasisidmon.

Buta ha hunapan an aton mga mata,

Pirme nakaandam an pan-abat ta.

Mahagkot, mahinay an sariwa nga hangin,

Mamara, mahadlat an aso ha haring.

Dako an kaibhan han nuknok ngan namok,

May dara nga mensahe an mga huni ngan dalugdog.

Kilalal-on hin maupay an pagkaiba-iba

Han nagkakahulog nga mga sanga

Han katumba han mga kahoy o mga bagakay nga nabuto

Tikang ha alingawngaw han putok han punglo.

Ngan antes mawaswas an yamog han mag-aga,

Antes pa magwarak an tiarabot nga lamrag,

Pagtitirub-on naton an natirok nga bag-o nga kusog.

Hihipuson an mga gamit ngan mag-aandam han paglakat.

Isesekreto han lagas nga bukid an uruunina nga paghapil

Ngan mamingaw nga maghuhulat ha utro naton nga pagbalik.

Kumplikado an dalan han ginhahasog nga gerra

Pero ha kada pagsagka ngan paglugsong

Pirme seguruhon an aton pagsulong.

Nakakawait an direksyon han aton nga larangan

Pero kabisado naton an tukma nga estratehiya

Para maglingkod

Ha masa

Para magpasalamat

Ha ira

Para magbigay pagpupugay

Ha mga namartir nga kasama

Ngan para tumanon an aton panaad

Nga ighalad an kadaugan

Ha altar han rebolusyon.

===========

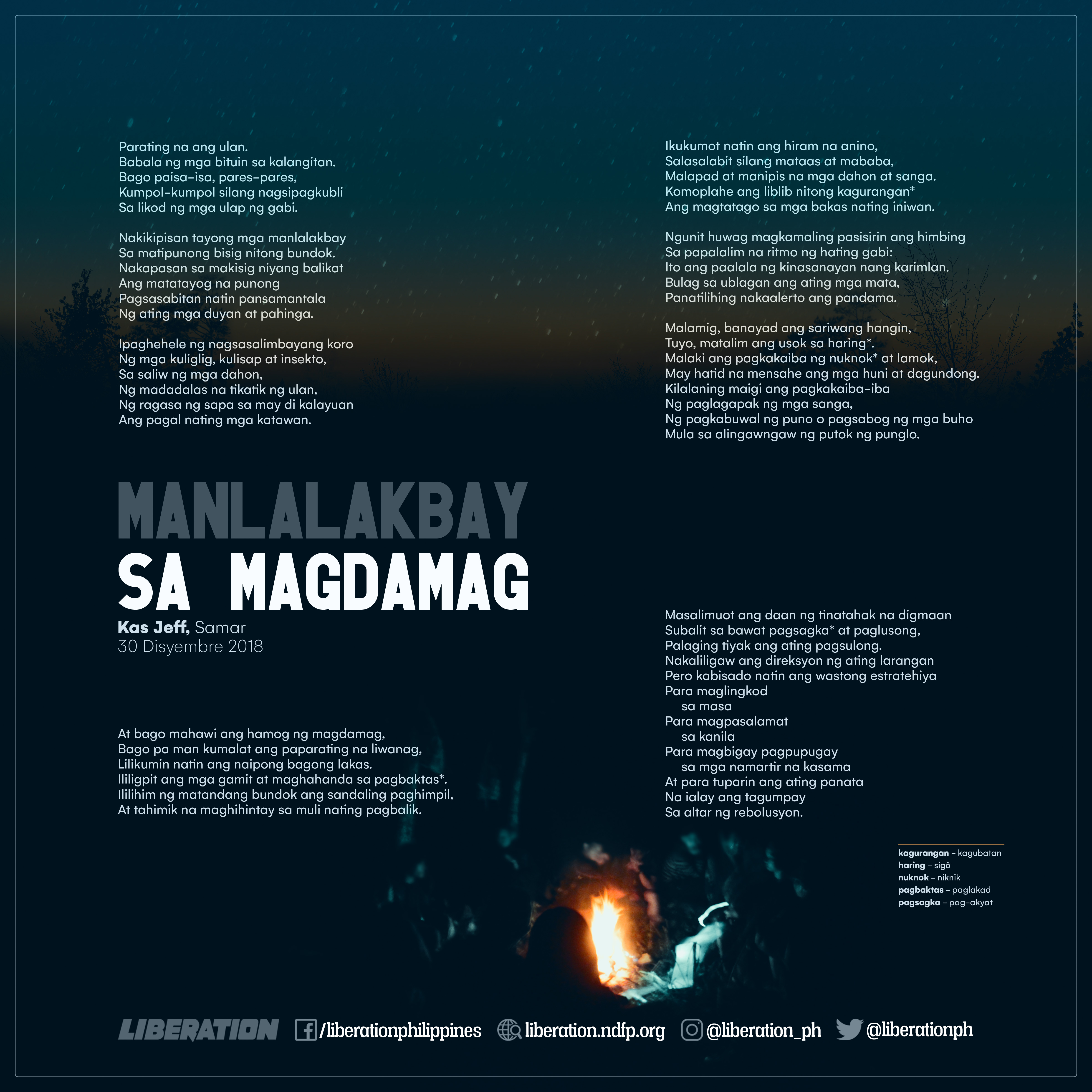

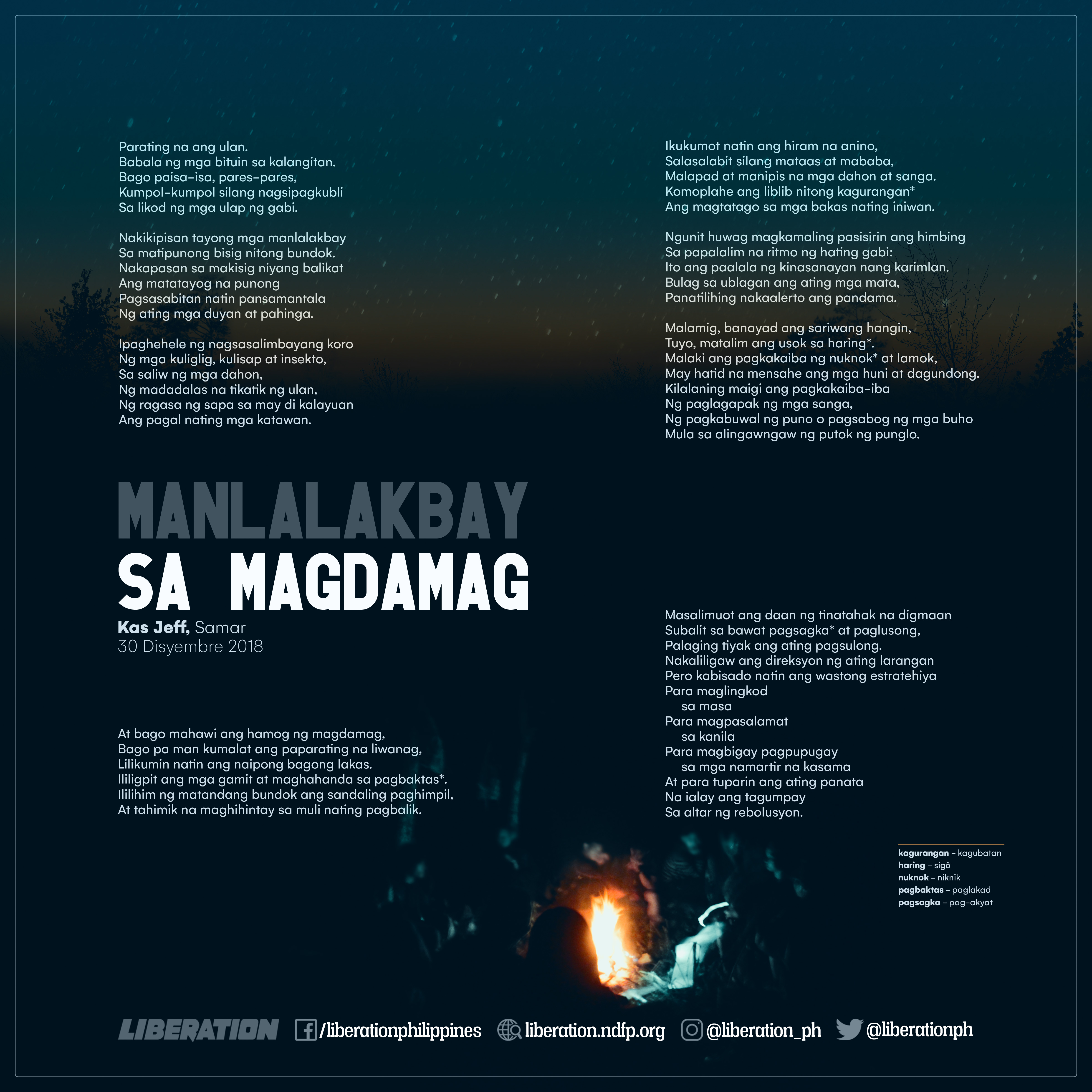

MANLALAKBAY SA MAGDAMAG

Parating na ang ulan.

Babala ng mga bituin sa kalangitan.

Bago paisa-isa, pares-pares,

Kumpol-kumpol silang nagsipagkubli

Sa likod ng mga ulap ng gabi.

Nakikipisan tayong mga manlalakbay

Sa matipunong bisig nitong bundok.

Nakapasan sa makisig niyang balikat

Ang matatayog na punong

Pagsasabitan natin pansamantala

Ng ating mga duyan at pahinga.

Ipaghehele ng nagsasalimbayang koro

Ng mga kuliglig, kulisap at insekto,

Sa saliw ng mga dahon,

Ng madadalas na tikatik ng ulan,

Ng ragasa ng sapa sa may di kalayuan

Ang pagal nating mga katawan.

Ikukumot natin ang hiram na anino,

Salasalabit silang mataas at mababa,

Malapad at manipis na mga dahon at sanga.

Komoplahe ang liblib nitong kagurangan*

Ang magtatago sa mga bakas nating iniwan.

Ngunit huwag magkamaling pasisirin ang himbing

Sa papalalim na ritmo ng hating gabi:

Ito ang paalala ng kinasanayan nang karimlan.

Bulag sa ublagan ang ating mga mata,

Panatilihing nakaalerto ang pandama.

Malamig, banayad ang sariwang hangin,

Tuyo, matalim ang usok sa haring*.

Malaki ang pagkakaiba ng nuknok* at lamok,

May hatid na mensahe ang mga huni at dagundong.

Kilalaning maigi ang pagkakaiba-iba

Ng paglagapak ng mga sanga,

Ng pagkabuwal ng puno o pagsabog ng mga buho

Mula sa alingawngaw ng putok ng punglo.

At bago mahawi ang hamog ng magdamag,

Bago pa man kumalat ang paparating na liwanag,

Lilikumin natin ang naipong bagong lakas.

Ililigpit ang mga gamit at maghahanda sa pagbaktas*.

Ililihim ng matandang bundok ang sandaling paghimpil,

At tahimik na maghihintay sa muli nating pagbalik.

Masalimuot ang daan ng tinatahak na digmaan

Subalit sa bawat pagsagka* at paglusong,

Palaging tiyak ang ating pagsulong.

Nakaliligaw ang direksyon ng ating larangan

Pero kabisado natin ang wastong estratehiya

Para maglingkod

sa masa

Para magpasalamat

sa kanila

Para magbigay pagpupugay

sa mga namartir na kasama

At para tuparin ang ating panata

Na ialay ang tagumpay

Sa altar ng rebolusyon.

30 Disyembre 2018

Northern Samar

kagurangan – kagubatan

haring – sigâ

nuknok – niknik

pagbaktas – paglakad

pagsagka – pag-akyat

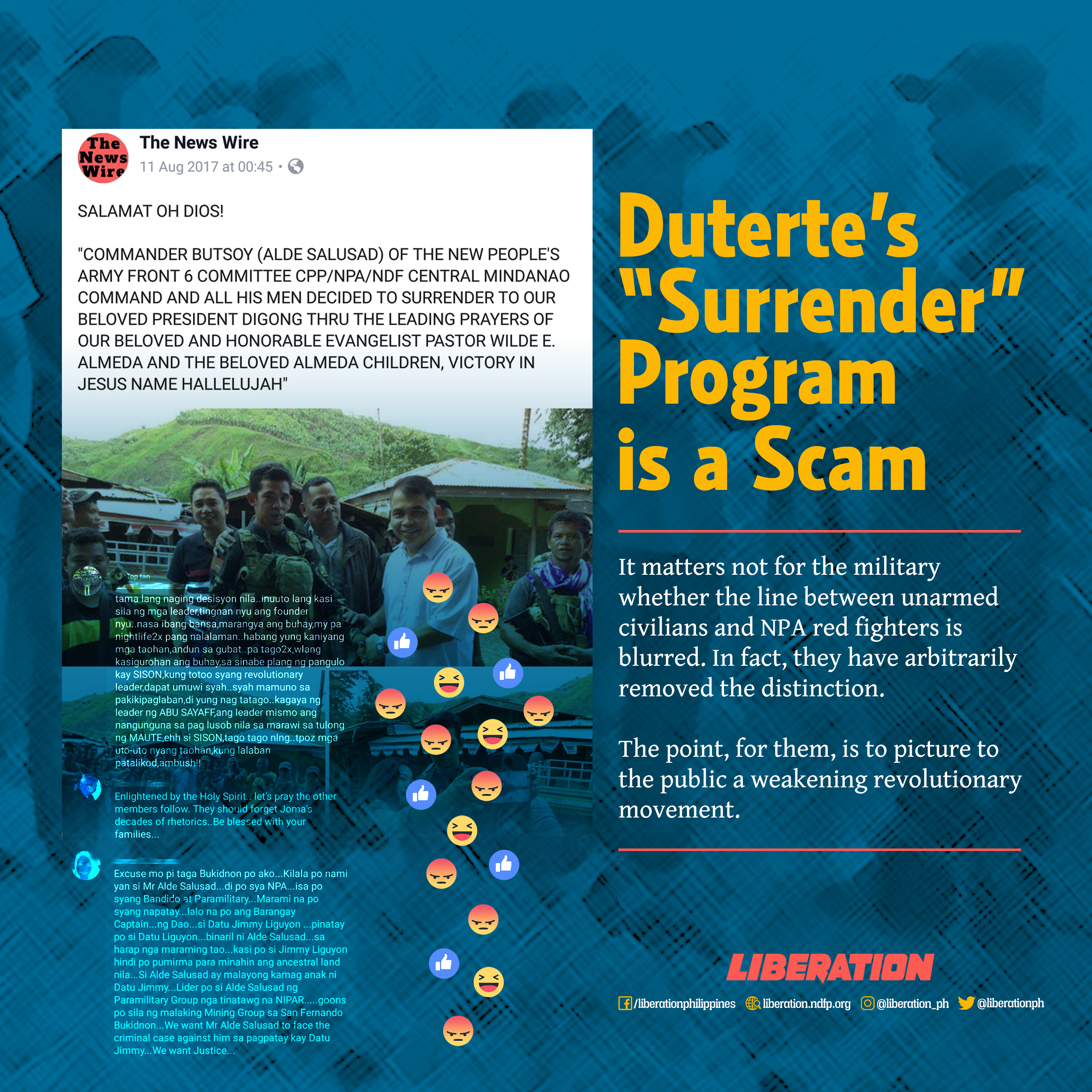

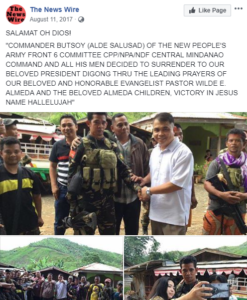

In August 11, 2017, five years after he killed Liguyon, Salusad was presented by the AFP as “NPA surrenderee” and was awarded Php100,000 in cash. Then in March 2018, the military included Salusad in the list of more than 600 names and aliases of alleged members of the CPP and the NPA in a petition for proscription filed at a Manila regional trial court.

In August 11, 2017, five years after he killed Liguyon, Salusad was presented by the AFP as “NPA surrenderee” and was awarded Php100,000 in cash. Then in March 2018, the military included Salusad in the list of more than 600 names and aliases of alleged members of the CPP and the NPA in a petition for proscription filed at a Manila regional trial court.