Pola: A Woman Toiler Turned Warrior

(Adapted from “Manggagawa, Mandirigma” by Ka Lina published in Ulos 2016)

by Pat Gambao

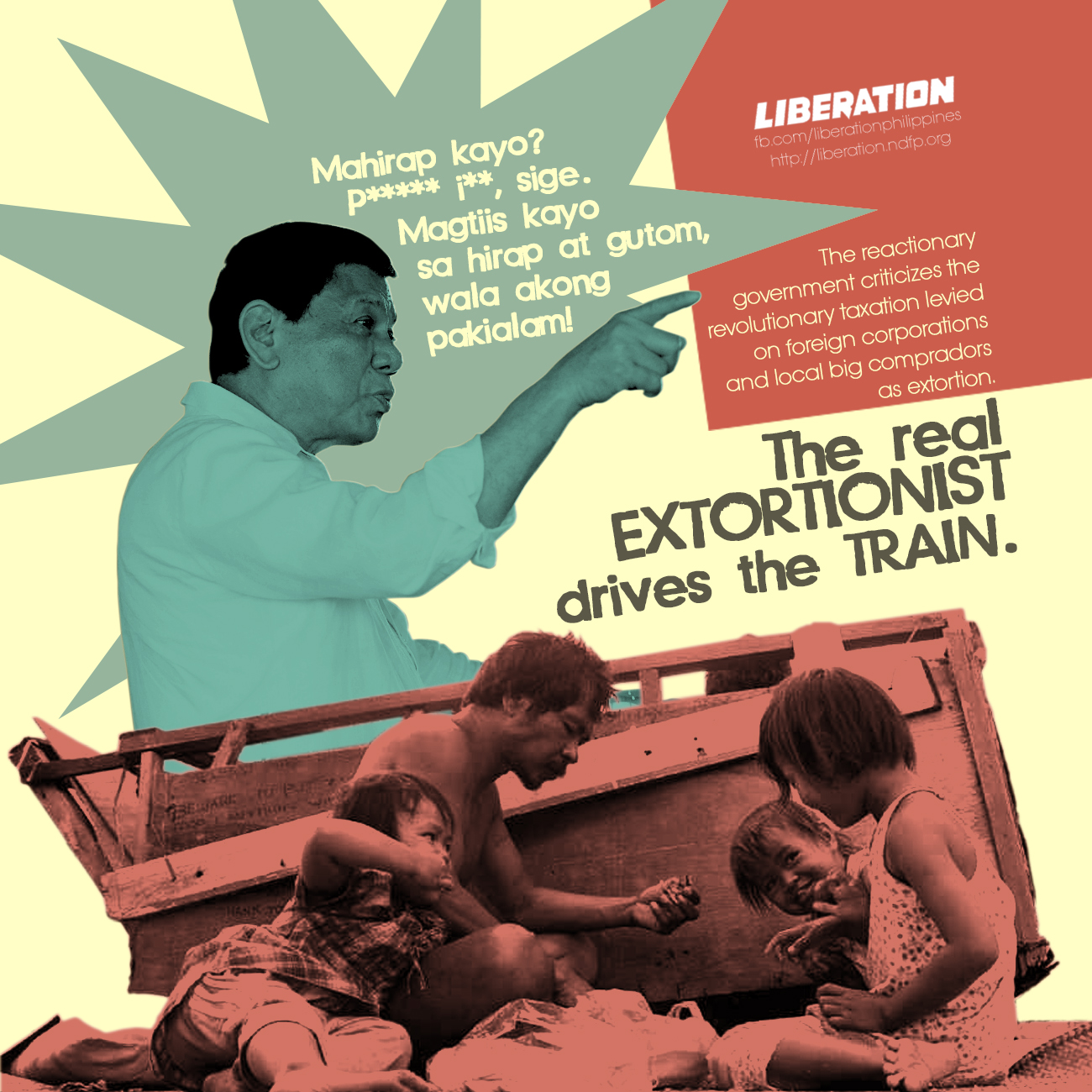

With the persistent pursuit for gender equality, women have transcended the patriarchal norm that a woman’s place is in the sanctity of home. With the advance of capitalism, women have entered new arena where their capability, vitality and intellect are recognized or rather harnessed. Yet as women toilers in factories and business establishments, they continue to experience the same degree, if not greater, of discrimination and exploitation.

Initiation to the world of the working class

Raised in a poor family who eked out a living from peddling food stuff for snacks in their barrio, Pola managed to finish high school but failed to pursue her dream of a college degree. Instead, she enrolled in a two-year course in a vocational school through the government’s “study-now-pay-later program”. In that so-called dual training, their only claim to being a student was the ID issued to them. They didn’t have a permanent classroom to pursue formal studies. Perhaps there really was no need as all they were taught to familiarize with different materials-wires, connectors and how to tape them together to assemble the harness of a vehicle. All they were taught were companies’ business concerns. In a semi-feudal society that served as mere supplier of semi-finished products to transnational corporations, perhaps those were all they need to know.

After three months, Pola and her classmates were sent to a factory for on-the-job training as part of the course. They were supposed to be student trainees yet they were made to work like regular workers as relievers or substitutes to absentees. They received P240 per day’s work, part of which went to payment of their tuition fees. The remaining one and a half years of the course were spent in the factory with such meager pay and without any benefit, not even the mandatory social security for workers.

Despite the rigor of the job, Pola worked hard, patiently waiting for the training to end in the hope that she would be taken in as apprentice. She got the job, true, but it did not take long before she was laid off.

Travails of a woman toiler

Thus began Pola’s rollercoaster journey into the world of commodity labor, exacerbated by the onslaught of imperialism’s neoliberal globalization as it dashed fumbling for a panacea to its crisis. The woman’s values of good-naturedness, patience and subservience inculcated by a feudal class society were fully taken advantage of.

Pola later applied as a saleslady in a well-known mall in their province. But she resigned after a month. She could not stand the difficult working condition and the ridiculous and repressive policy of the establishment. For a measly wage, she had to remain standing the whole day to reach her quota for the brand of dress apparels she was selling. There was a time when she was reprimanded for bringing her handkerchief inside the store without first registering it. Personal belongings had to be registered before bringing them in lest you would be accused of stealing.

From the job in the mall, Pola worked in an electronics company where she assembled “male” and “female” terminals used in television sets. But after more or less four months, her contract ended. This was the endo (end of contract) they call in the labor lingo.

Pola ended up in a food factory, where she was hired through an agency. With a spoon, she raced after the cups of noodles to determine if the noodles and condiments were of the right quantity or if needed to be reduced, add on, or changed. Also, if the machine that put on the cup lids was out of order, she had to do it manually. They worked by shifts in the factory. There were three shifts in all. But if a worker for the next shift was absent, she was obliged to take over and work up to 16 hours. Then again, it was endo after five months.

Pola also tried working as caddie in a golf course. She was an umbrella girl who trod on the heels of the golfer to shed him from the sunlight. But unable to stand the harassment from her bosses, she left the job after two months.

Through an employment agency in Makati, Pola was back as a factory worker. This time it was in a company manufacturing plastic lids for bottles of lotions, medicines, etc. Initially, her job was trimming the extra plastic around the lids to even them out; later, she was transferred to the packaging section. Sometimes, she relieved the operator of the machine that molds the lids.

As trimmer her quota was 6,000 plastic lids a day. Due to the thinness of the lids and the absence of a protective devise, her fingers often got wounded. As instant remedy, she would put on some adhesive tapes. But in the long run, her fingers have become numbed that she would not mind at all anymore. If she had not reached her quota, she was obliged to go on “overtime-thank you”, meaning overtime without pay. Again, after five months, endo. But she could continue working there as an “extra”- doing the same work, but with lower pay and without a contract.

Since life is difficult for Pola, any job is a welcomed treat just to earn a living.

The dawning of revolutionary consciousness

One day, coming home from an arduous day’s work in the factory, Pola met some students who stayed in their community. She was invited to sit-in to their discussions on the Philippine society and revolution. That awakened her to the stark realities-the immense oppression and exploitation of workers like her, as well as of peasants, professionals, youth, women and other sectors in society. She learned that their affliction was not destined. It was designed-a sinister scheme of the ruling class to hold on to power and wealth. But the greatest lesson she learned from their discussions was the solution to the people’s problems.

Pola could not contain her rage, as well as anxiety, with that realization. All along she had been entertaining the thought of leaving her job in the factory which did nothing but extract the workers life blood and sinew to accumulate huge profits for the capitalists. After thinking it over for days, weeks, and on to several months, Pola finally decided to work full time in the movement. This was the most decisive action she took in her whole life. She has the chance now to look at life from a different perspective and open up to new opportunities, best opportunities.

Sometimes, she reminisced about her past life in the factory, in the mall, in the golf course and how she spent it in vain. She could do nothing about it now but it would serve as a potent inspiration for her to get involved and take action to change this oppressive, unjust structure.

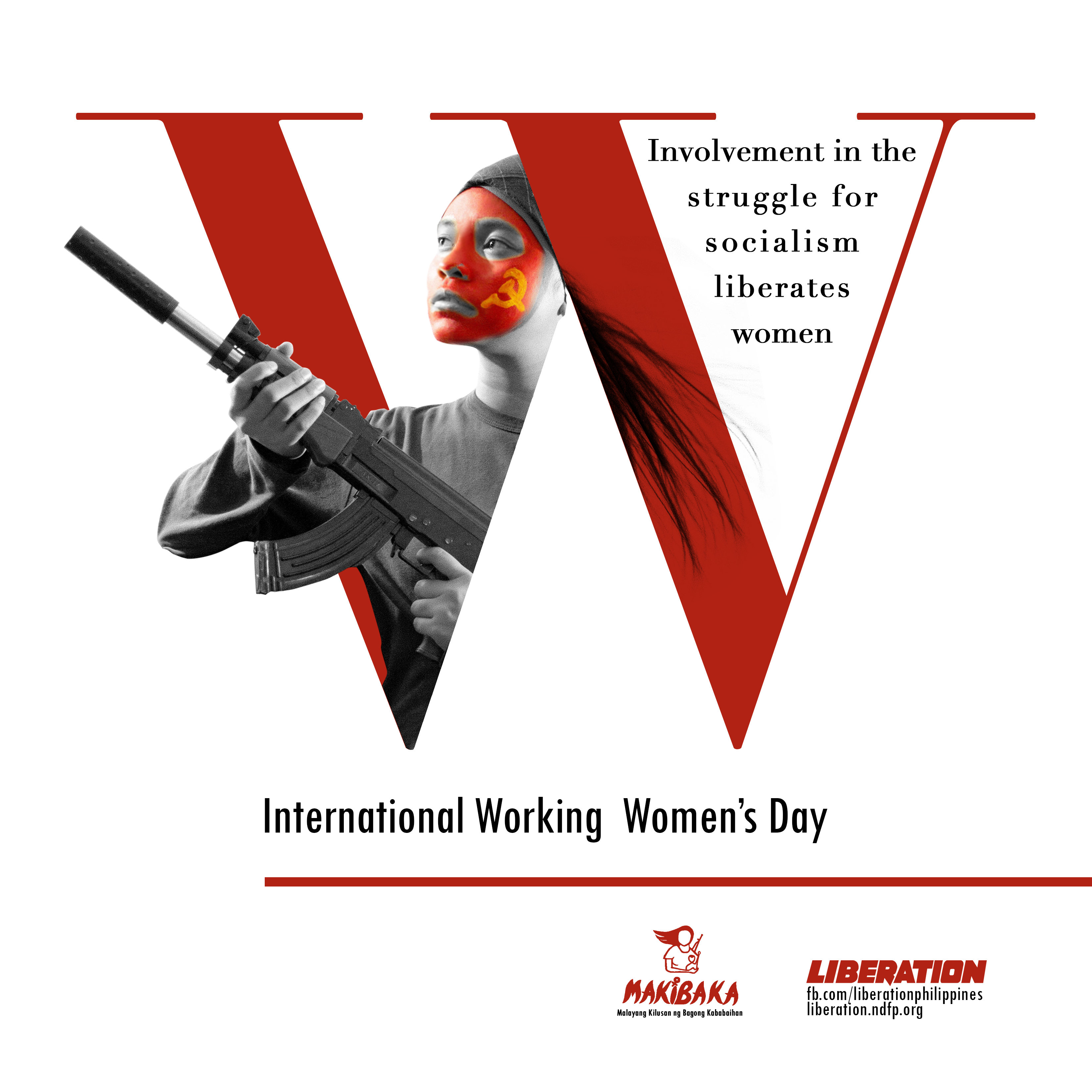

Smashing the chains

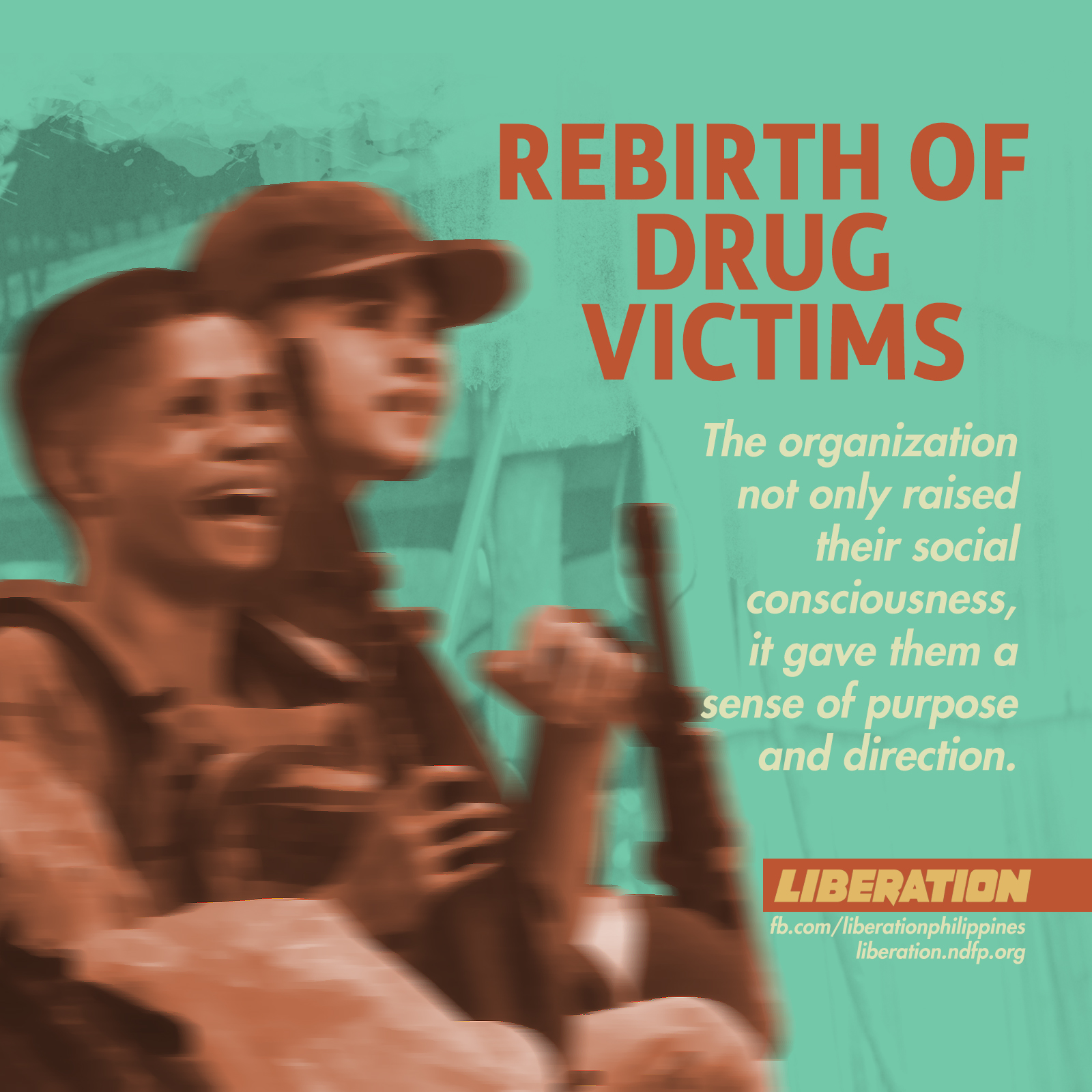

After more than a year of working in an urban center, Pola is now Ka Lina, a red warrior of the New People’s Army. She no longer held spoons, wires, connectors, dresses, umbrellas or plastic lids. She now carries an armalite. The broad countryside is her school and each day they delve into the strategies of the people’s war that will topple the semi-colonial, semi-feudal structures that oppress the people.

She is optimistic about the future, not only hers and her family’s, but also of the coming generations. Although she may not live to see victory, she is confident that time will come when the wealth that the people produce will serve not only a few but all. She vows to commit everything about her for the revolution, which will liberate the people from the fetters of exploitation and oppression.###