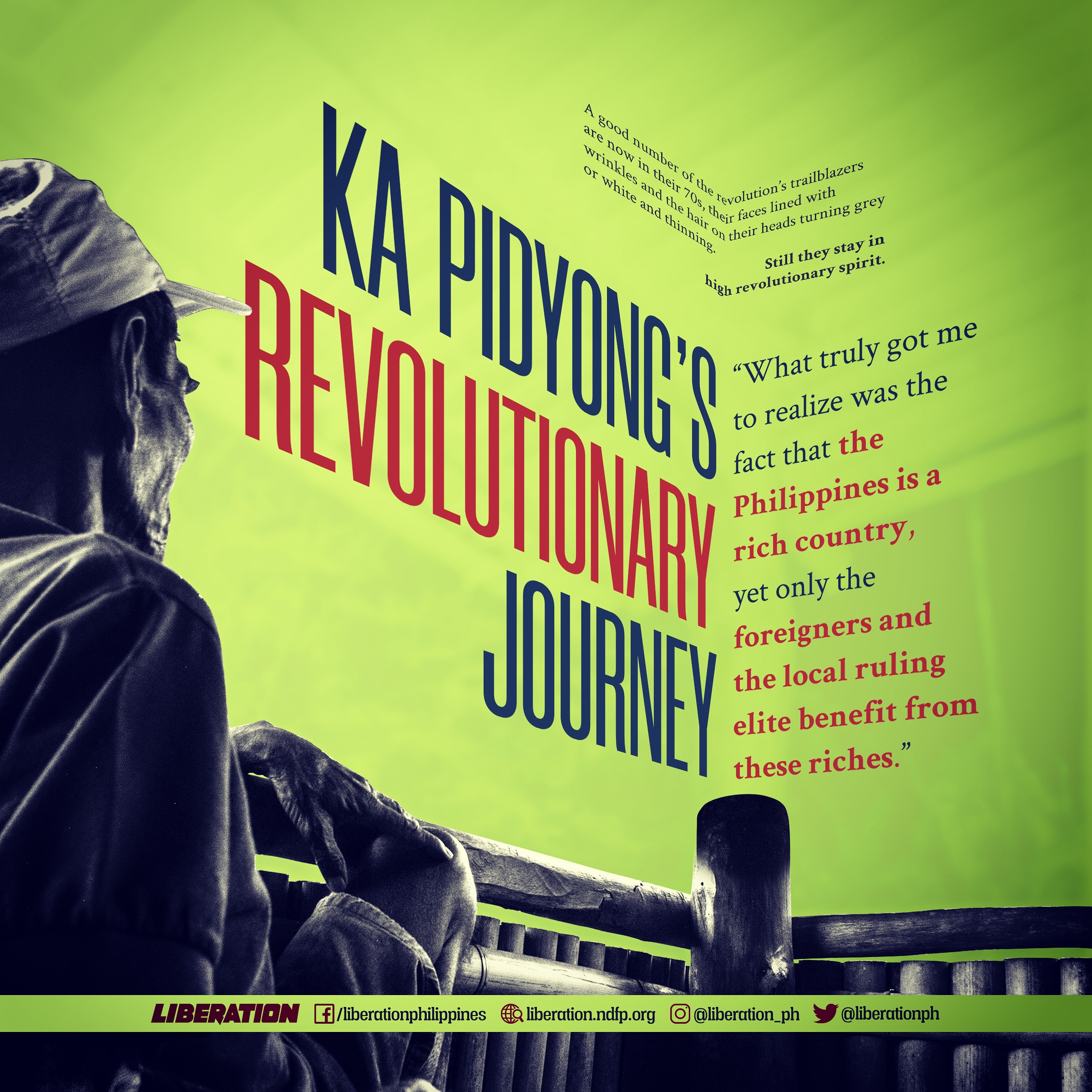

Ka Pidyong’s Revolutionary Journey

The 75-year old Ka Pidyong couldn’t contain his laughter as he recalled the first time he met members of the New People’s Army (NPA) in their community, an upland barrio in Northern Luzon. He was among the first batch of peasant men and women who welcomed comrades from the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and the NPA in 1971, when the twin revolutionary organizations were in the formative stage.

“There were seven of them,” he said in Filipino, grinning. “Only one had an armalite rifle, while the others had carbines, a shotgun, and a caliber .38 handgun— all teka-teka guns (teka literally means “wait” and refers to low-caliber guns). Of the last member of the team, he remembered vividly, “He had no gun, only a kaldero (a metal pot used to cook rice).”

“Three years later, they were already 16 and fully armed,” Ka Pidyong mused. “We were so happy. Our morale was high because 12 of them were recruited from our village.” Some of the original members had been redeployed elsewhere, he remarked enthusiastically, “They continued to grow, so did we.”

Decades after that first contact with the people’s army, the villagers have now established, painstakingly, their own organs of political power: the revolutionary mass organizations of peasants, women, and youth. A revolutionary council has also been elected and now governs their communities. In 2017, members of the mass organizations—representing the unity forged by the CPP, the NPA, and their allies—held their second elections in less than five years.

Setting the Revolutionary Fire

Not long after the first meeting with the NPA, community leaders teamed up with the NPA to go to different mountain villages and those near the town center. They held meetings, education sessions, and explained to the masses the ills of our society and the proposed long-term solution to their situation.

“What truly got me to realize was the fact that the Philippines is a rich country, yet only the foreigners and the local ruling elite benefit from these riches,” Ka Pidyong said.

The education session was followed by many more until, “ang dami ko nang alam (I learned so much)” Ka Pidyong continued, beaming.

The peasants in this guerrilla zone are mostly landless, some tilling a hectare or two. The communities are nestled in a public land, where any moneyed individual can claim ownership over parts or all of it in blatant disregard of existing laws. All too often, the peasants had been victims of traders who preyed on them by selling farm inputs and implements that were overpriced and buying their farm produce at dirt-cheap prices. The government, too, attempted several times to evict the peasants and give way to so-called development projects, but did not succeed.

The series of education sessions was later followed by the establishment of a local chapter of the Pambansang Katipunan ng mga Magsasaka (PKM, National Association of Peasants), one of the founding affiliate organizations of the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP). The establishment of the Makibaka (Makabayang Kilusan ng Bagong Kababaihan) followed after a few years.

As the organizations expanded, Ka Pidyong and other comrades, also thought of ways to tackle their revolutionary tasks more effectively, such as: how to give education to those who are not literate; how to maintain communal farms, form a militia unit in the barrios for their security, and how to efficiently support the various needs of the NPA— the latter task they took to heart most fervently. The welfare of the NPA fighters has always been at the forefront of the masses’ concerns. Even in times of calamities, when there was hardly anything to eat, the masses saw to it that there was food for the Red fighters.

Makibaka members took the lead in taking care of the children of fulltime cadres and Red fighters. They looked after their schooling and overall welfare. The women likewise started the health and sanitation programs, which include production of herbal medicine. The youth were organized under the Huwarang Bata (Model Youth), which initiated sports programs, among others. In those years, when members of the NPA came back from tactical offensives, the youth would welcome them with revolutionary songs.

It has been a long, arduous, but victorious journey for those who blazed the revolutionary trail in this guerrilla zone.

Tempered by Struggle

Leaders of the PKM identified two most trying moments they had experienced in their almost 50 years in struggle: the Party’s disorientation in the late 1980’s until the early 1990’s and the intense militarization during the same period.

But they held the fort, they said, never losing track of the revolution’s onward march, much more the will to push it to victory. Even in those difficult times, when the enemy surrounded them, in their hearts and in their minds they knew where they stand—to serve the Party and the masses.

In fact, while the AFP encamped at the barrio for 14 years, several organizing groups and revolutionary mass organizations were established in the communities surrounding the barrio.

“No one was ever recruited into the AFP’s paramilitary unit. There were a few who almost agreed to be recruited but we persuaded them to back out,” said Ka Pidyong with a chuckle. Ka Pidyong was arrested by the military but, after his release, went into hiding several times after because of the continuing threats of re-arrest.

At the time, the NPA stayed away from the barrio center since their presence would cause unnecessary confrontation with the government forces that would affect the unarmed civilians.

But such restraint was no longer exercised during the Party’s disorientation. The situation then turned intense, pitiful for the masses who had to bring supplies, food into the remote mountainous areas where the NPA retreated after launching tactical offensives. This was the period when military adventurism seeped into the NPA ranks and mass work and agrarian reform tasks took a back seat to tactical offensives that were launched one after another.

Ka Pidyong was among those in the barrio who disapproved the swing to military adventurism, saying it was not time to show off the NPA’s military strength in their guerrilla zone. His memory of how the NPA had shifted its focus and the change in its attitude towards the masses was still fresh. “Yung mga kasama noon wala na, kapag pinupuna ayaw na (At that time the comrades didn’t want to accept criticisms).”

Sadly, Ka Pidyong was among those who were suspected as military agents within the movement during the anti-infiltration campaign. Although he had ill feelings then, now he shrugs off the whole experience. During the rectification period, the Party and NPA cadres and red fighters humbly criticized themselves before the masses and members of the revolutionary organizations as they explained to them the rectification process.

The elders in the community did not mince words in criticizing the Party and NPA members, which the latter wholeheartedly accepted. What is important is the rectification of the errors, which led to growth and strengthening of the Party, the people’s army and the mass organizations.

One with the Party and the People’s Army

A good number of the revolution’s trailblazers are now in their 70s, their faces lined with wrinkles and the hair on their heads turning grey or white and thinning. Still they stay in high revolutionary spirit. They have been in the movement for at least 47 years. Some of them were just about 12 years old when introduced to the movement.

“I am satisfied. Despite my age and ailment, I am still able to help in whatever way I can,” Ka Pidyong remarked. He quickly added, “And, I’m energized to see young people, from our place, from other places, from the cities who come here and stay with us.”

“If the end of our struggle is still far away, where we started from is now much farther away. Let’s continue fighting,” he added.

It took several probing questions from Liberation on how these trailblazers felt about being the bearers of revolutionary power in their communities before they could answer. There was initial silence, a long silence. Tears welled in the eyes of some of them. Clearing his throat, Ka Pidyong spoke up first. He firmly declared, “Without the Party and the NPA, we have nothing.” ###

#PeasantMonth

#ServeThePeople

#JoinTheNPA

—–

VISIT and FOLLOW

Website: https://liberation.ndfp.info

Facebook: https://fb.com/liberationphilippines

Twitter: https://twitter.com/liberationph

Instagram: https://instagram.com/liberation_ph