The Trail to Victory

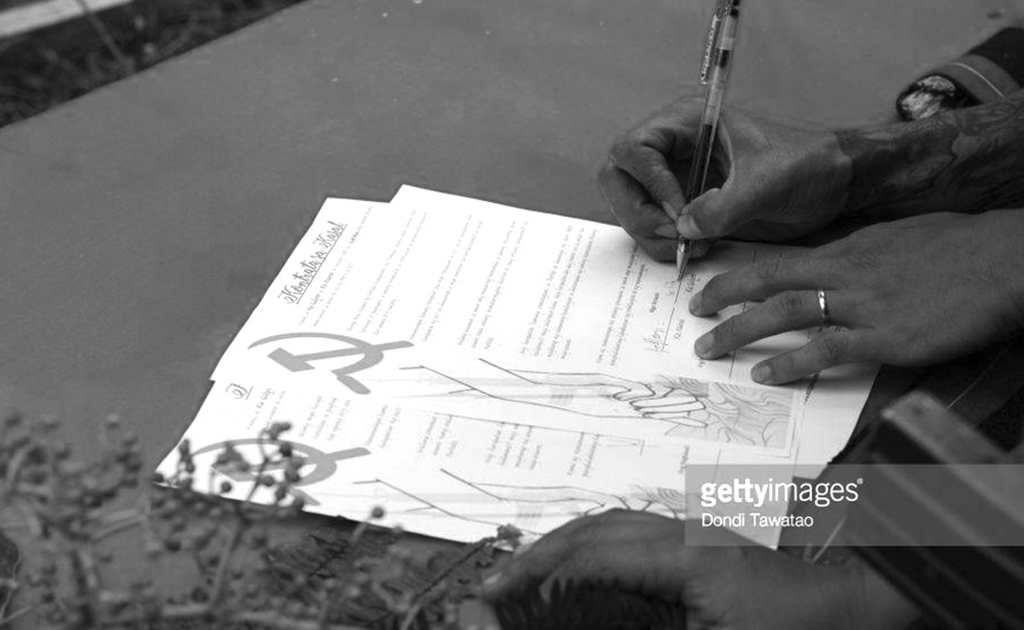

A month before the celebration of the 50th year founding anniversary of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), Ka Krish, the youngest daughter of Ka Lusyo and Ka Remy exchanged vows with a comrade in the New People’s Army (NPA). The wedding, officiated by a senior member of the Party, is partly a fulfillment of Ka Lusyo and Ka Remy’s hopes and dreams.

For Ka Lusyo and Ka Remy, their daughter’s wedding in the Party was a victory as a couple in raising a new generation of revolutionary.

It also sealed their lifetime commitment to the Party. With Ka Krish, the couple are sure that a new generation will pick up the torch they carry, the arms they brandish, and the banner they wave high to further advance the achievements of the Party.

This new generation shall fulfill the dream and enjoy the fruits of a just, humane, and prosperous Philippines.

The Beginning Of Their Trail

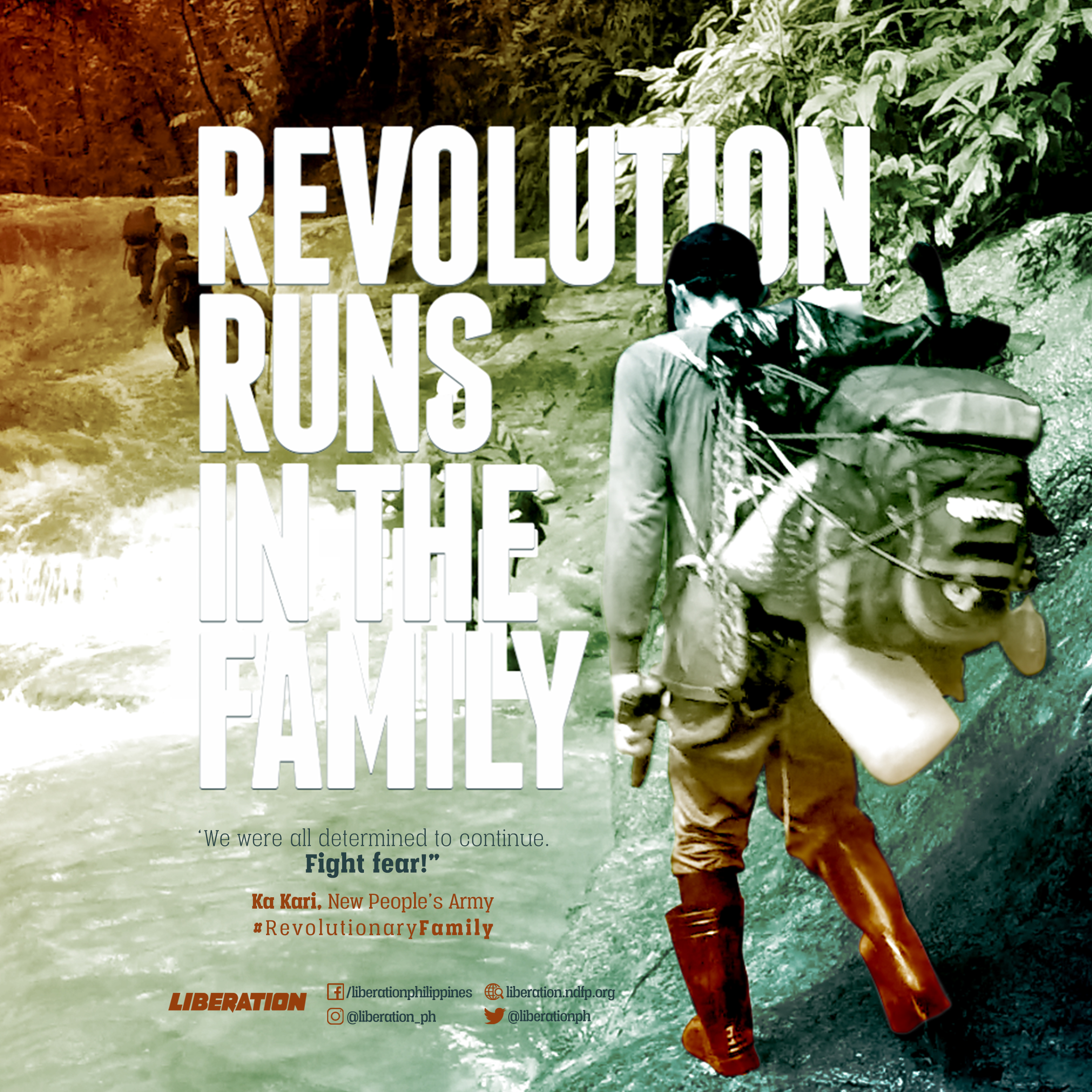

In 1975, Ka Lusyo’s barrio in a remote town in Eastern Visayas was militarized and became a “no man’s land”—where the military shot people on sight, for no reason. Villagers had to evacuate and resettle in the forested area. There they met the NPA.

“I was 17 going on 18 when I tagged along with the red fighters doing propaganda and education work until finally I decided to join them fulltime,” Ka Lusyo narrated. After attending a training on step-by-step organizing, his first assignment was to lead a team of three in organizing five barrios.

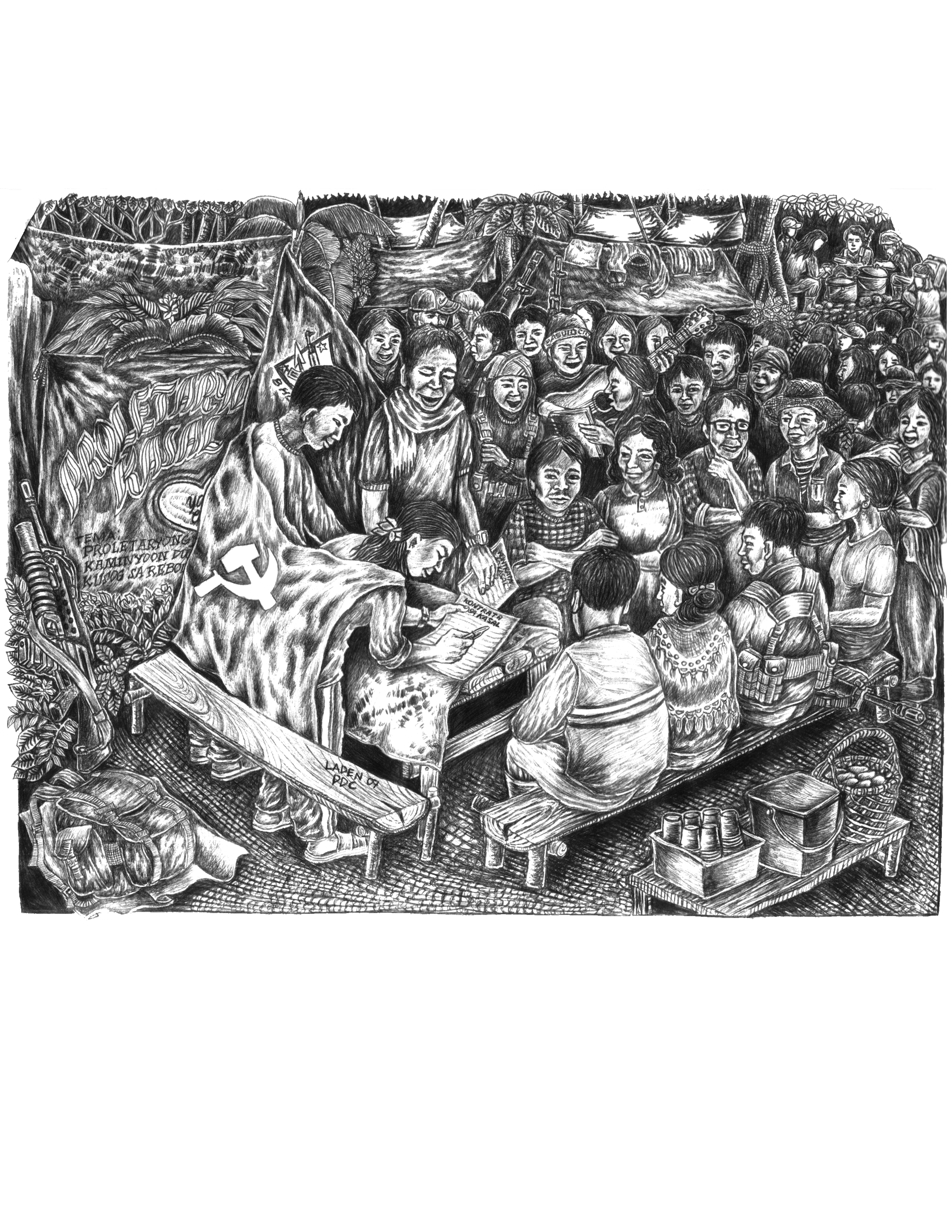

“Yes, we were armed. But, except for the revolver that I carried, everything else were pugakhang (home-made gun in Waray language),” Ka Lusyo confided. The team usually work at night going from one barrio to another, holding mass meetings, imparting the knowledge it has learned from comrades in the red army. The masses welcomed and appreciated the discussions about their issues and situation. Enlightened, they cherished and regarded the red army with high esteem.

The next time Ka Lusyo reported back to the squad headed by Ka Bakê, he was given a new assignment. He was trained for the medical team. After more than a month of training, Ka Lusyo became the medical officer of the squad. Later, he would become a commander of the NPA.

His first involvement in a tactical offensive was in the simultaneous attacks in two towns. Those were their first victorious battles. It was followed by an ambush in another town.

“It was the first time I was issued an armalite, my first time to get hold of an automatic rifle,” Ka Lusyo elatedly related.

After that, their unit moved to another town, carrying out ambuscades on the way. In the process, they were able to gather arms from the enemy troops. Their squad then became two to form an undersized platoon. That was in 1979. “That was how we were then, tiklop–buklad (close, open). We split into squads, then merged again into platoon. The attacks on the enemies were frequent and continuous as we proceeded to our destination,” Ka Lusyo narrated.

The red army continued moved around the province—arousing, organizing and mobilizing the masses. In the same vein, tactical offensives were frequent and reverberated all over the province. The Red army was high spirited as if victory was just a leap away.

Love In The Time Of The Revolution

“It was in the North when I met Ka Remy, sometime in 1981. She was a correspondent of our newsletter,” Ka Lusyo began to speak of their love life.

Ka Remy was in Manila when the revolution started in Samar. But, Ka Remy had other plans in mind. Knowing she would not get the nod of her parents, Ka Remy ran away from home to work as household help in the city. That was in 1972.

When the revolution in Samar was gaining ground, her father bade her to come home for fear that they might not see each other again. That was in 1979. She was 19. Meeting a group of enlightened youth in their barrio, she readily joined them. She became a member of the organizing committee in the barrio. But since she was new in the group and needed to be oriented and educated, her tasks at first were confined to making placards for rallies and postering. Later, she realized she needed to do more for the struggling masses and against the onslaught of the fascist rule. After attending courses in the revolutionary movement, she became part of the barrio militia.

“Intelligence work was one of our tasks although I was not so good in it,” Remy admitted.

Her father did not approve of her joining the group. But when a comrade came to talk to him about her going on full time, he consented although tearful. “The next time I visited my father, he told me neither to come home nor see my friends again. He had told everyone I went back to Manila,” she said.

In the people’s army, Ka Remy was trained in all aspects of the hukbo’s work. But when Ka Remy’s group launched a tactical offensive, they did not include her. She was left behind to prepare the meals instead. She resented it. She felt her training was in vain. She felt they did not have confidence in her capability. To rectify, she was later made to join in all the activities of the group.

In 1980, she was transferred to staff work as correspondent for their propaganda work. That was the time she met Ka Lusyo.

Brought together by their work in the movement, Ka Remy and Ka Lusyo’s friendship flourished. Ka Lusyo asked for the permission of both their collectives to court Ka Remy, as practiced in the revolutionary movement. It took months of distance courtship before Ka Lusyo was accepted and two years of distance relationship before they got married.

The distance relationship has suffered the acid test when no letter came from Ka Lusyo for a long time. The relationship almost ended.

“Only when he arrived did I learn he got sick. It could not be denied, he still reeked of medications,” Ka Remy remarked in jest.

The two got married in early 1984 but they stayed together for only three days as Ka Lusyo had to return to his area of responsibility. Meantime, Ka Remy’s assignment also changed—from correspondent she was assigned to do mass work again.

Most of the time, the two performed their revolutionary tasks in separate locations, often away from each other. When Ka Remy was arrested and detained, it took more than a year before the couple met again. Ka Remy could no longer remember Ka Lusyo’s face. It was not surprising because the time they had been together was indeed brief. But this time, upon Ka Remy’s release, they no longer separated.

Together they wove a romance that endured the test of time, difficulties and life-and-death situations. They were together in the raids and ambuscades that were launched.

Their romance blossomed in the midst of the revolution, steadfast as the objective they were fighting for, strong as the determination to overcome all travails and risks, hopeful and faithful that this just war will birth a free, prosperous, and just social system that their children and the generations to come will enjoy.

Ka Remy and Ka Lusyo had four children, the youngest who was born by ceasarian section, died. The children were raised amidst the formidable situation of a war for liberation. When older and weaned from breastfeeding, the children were taken cared of by the masses or some relatives. They came whenever Ka Lusyo and Ka Remy’s unit are encamped, especially when there were celebrations. “LR, my second child, was so dogged and loquacious. He prided introducing himself as my son,” Ka Lusyo was nostalgic.

Surviving The Disorientation

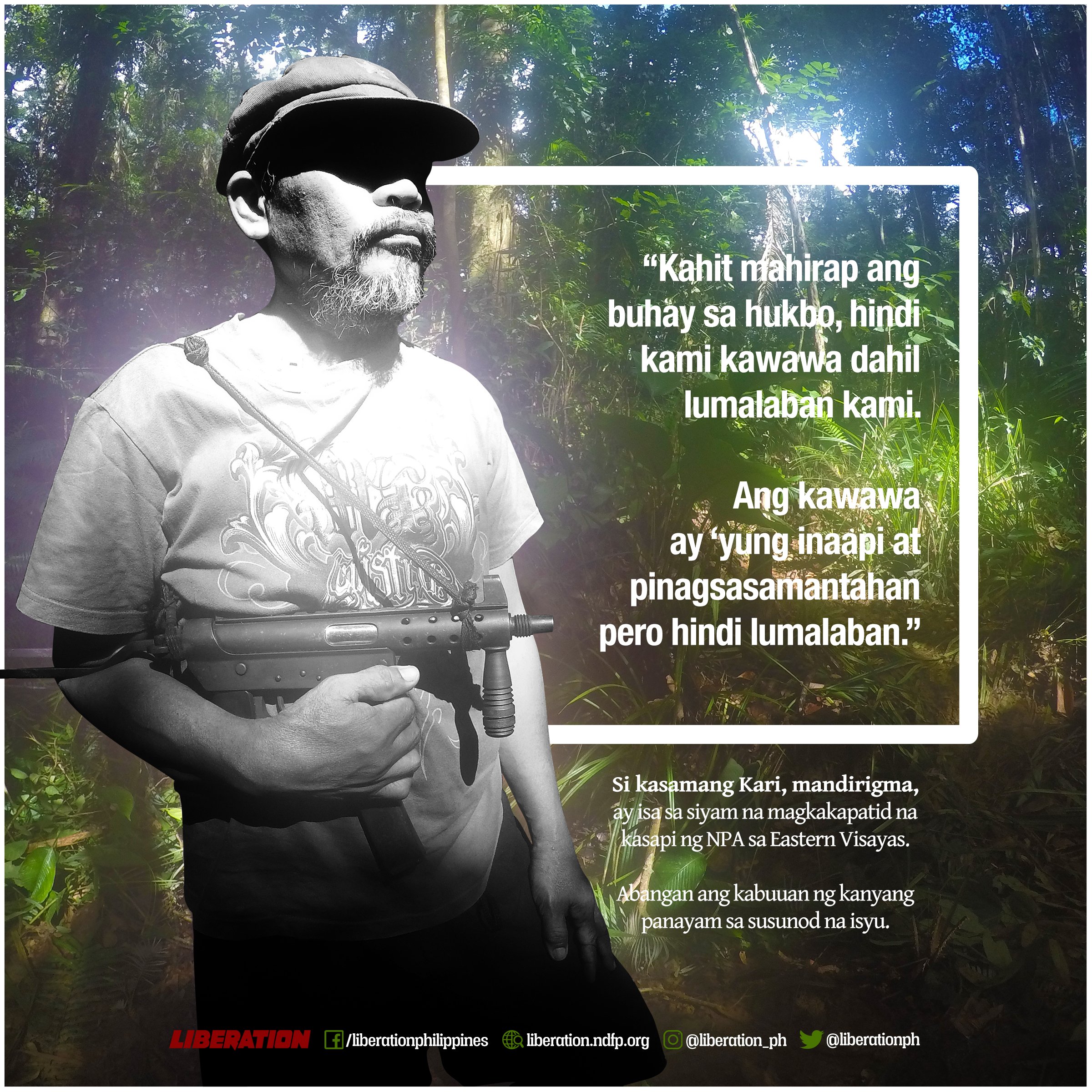

Having attained impressive achievements not only in the armed struggle but also in the agrarian revolution and mass base building, the revolutionary forces in Samar were overwhelmed. Influenced by the disorientation of some cadres in the national leadership, their impetuosity blurred the basic principle of protracted people’s war as they dreamed of quick victory. Regularization of army formation to pursue “strategic counter-offensive” in the 80’s led to the abandonment of mass work and agrarian revolution.

The couple have been very much embroiled in this traumatic nightmare that shook the revolutionary movement. In 1988, the battalion was formed. Ka Lusyo became a third commander in the succession of commanders of the battalion. Ka Lusyo was commander for Alpha. Ka Remy recalled the numerous tactical offensives launched by Alpha.

The battalion was dissolved in 1993, when the Second Great Rectification Movement was launched by the CPP.

Through all these setbacks, Ka Lusyo and Ka Remy remained strong and resolute in their commitment knowing for whom and for what purpose the people’s revolution is all about. They humbly acknowledged the errors of the past and proceeded towards rectification.

The rectification campaign in Eastern Visayas began in 1993. Red fighters and commanders went back to the barrios they left behind, owned up to the errors, and criticized themselves before the masses. The red fighters, commanders, and mass activists returned to the basics—mass work, organizing, propaganda work, and education campaign. Mass organizations, people’s militia and organs of political power were rebuilt. Basic Party organizations were established. Mass struggles and united front work were restored. In 1996, it was said that the rectification campaign in the region has “arrested and reversed the decline of the revolutionary movement.”

Meanwhile, Ka Lusyo and Ka Remy’s offsprings grew up all woke and determined to carry on their parents’ mission. All became full time Red warriors although Gail, the eldest, left the army when she got married.

For Ka Lusyo and Ka Remy, the trail is all set for the total victory of the national democratic revolution to the dawning of the socialist construction in this land.###

#ServeThePeople

#RevolutionaryFamily

#CherishThePeoplesArmy

—–

VISIT and FOLLOW

Website: https://liberation.ndfp.info

Facebook: https://fb.com/liberationphilippines

Twitter: https://twitter.com/liberationph

Instagram: https://instagram.com/liberation_ph

“Marahas ang digma, pero mas marahas ang mga pinag-uugatan nito. Kapasyahan natin ang pagtahak sa landas na ito. Ang ating pagpili ay siyang ating pagtindig. Ang ating pagtindig ay atin ding panata. Panata, hindi lamang sa iyo, mahal, higit lalo sa bayan nating minamahal. Ang mga kabundukan ang ating paraisong tirahan, at sa piling ng minumutyang masa tayo ay napapanday.

“Marahas ang digma, pero mas marahas ang mga pinag-uugatan nito. Kapasyahan natin ang pagtahak sa landas na ito. Ang ating pagpili ay siyang ating pagtindig. Ang ating pagtindig ay atin ding panata. Panata, hindi lamang sa iyo, mahal, higit lalo sa bayan nating minamahal. Ang mga kabundukan ang ating paraisong tirahan, at sa piling ng minumutyang masa tayo ay napapanday.