Solving the Drug Problem (Part 2 of 3)

China’s Experience Under Mao

by Pat Gambao

In the years prior to the victory of the Chinese revolution led by Chairman Mao Zedong, China was mired in the quagmire of addictive drugs. Profiting immensely from the drug trade, foreign capitalists in cohort with the local ruling class dope the populace. Some 70 million Chinese, including children were hooked on drugs. Despondent about their miserable conditions, the poor found escape in the fleeting comfort of the illicit substance. The consequences were dismal and despicable. To finance their addiction, women resorted to prostitution, parents sold their children, money for food went to drugs.

Upon victory of the revolution, the new people’s republic launched a mass campaign against addictive drugs not by the power of the gun but through the people’s movement. Since the addicts among the poor were mere victims of a depraved system, they were not treated like common criminals nor human thrash but were helped to lick their addiction. The revolutionaries organized the masses in the communities to help educate and convince their neighbors and kin who were hooked into drugs to kick the bad habit. Community members burned drugs to emphasize their abhorrence of these. They also stopped the supplies of addictive drugs by busting drug trade networks. In support of the drug campaign, radios and newspapers carried news and stories on the ill effects of drugs and its detrimental impact to the development of the new socialist society. The revolutionaries relied on the organized masses from the cities to the countryside to end the manufacture, trafficking and their use.

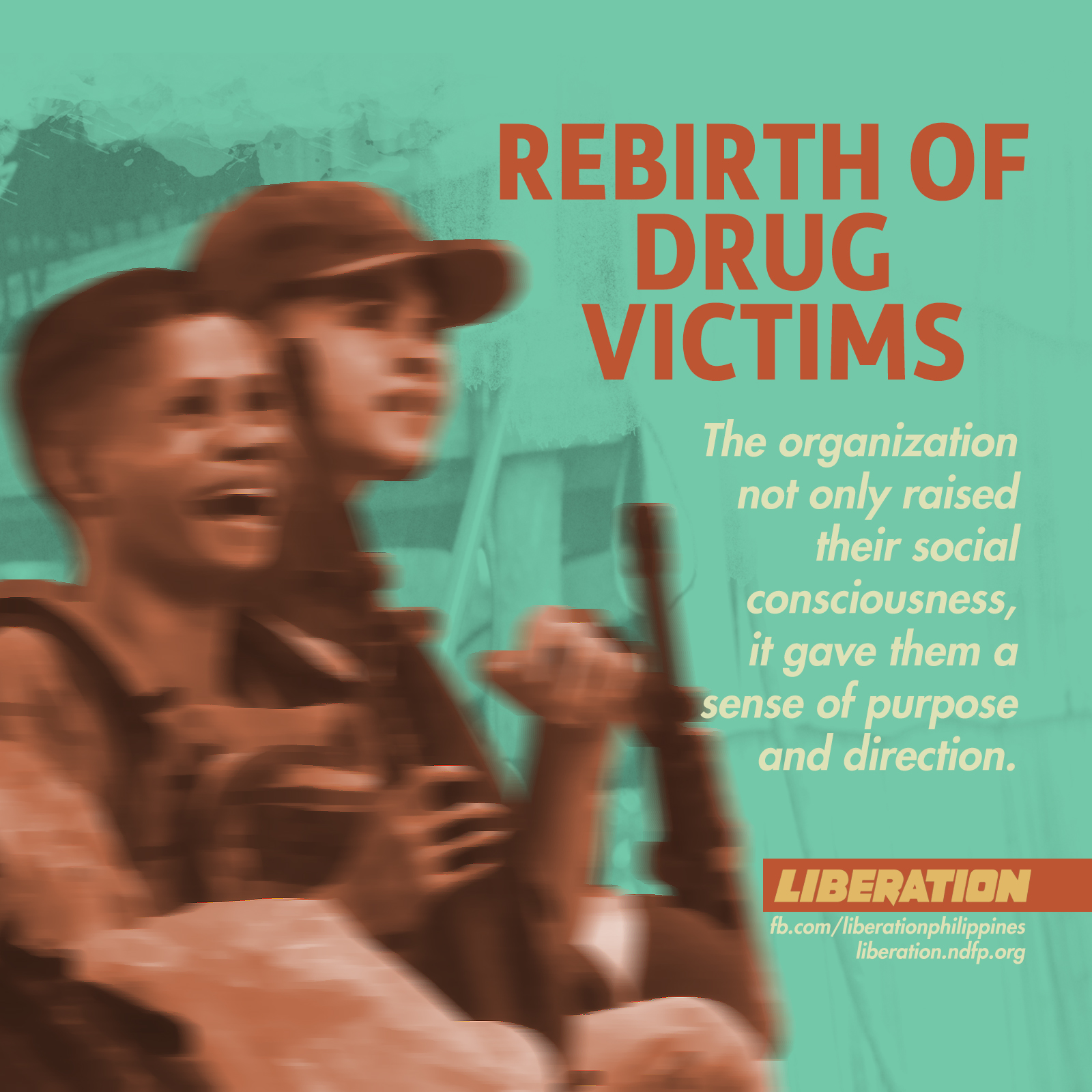

Class distinction was made between the poor junkies, who were victims of the system, and the filthy rich drug dealers, who nurtured the system to their advantage. The poor victims needed help while the big drug dealers were considered enemies of the people. The victims trusted the new people’s republic that they had no fear in seeking help. They were rehabilitated and assisted in the withdrawal process. They were praised for their efforts to get clean from drug addiction. They were organized, re-educated and trained for meaningful jobs that the new socialist society provided. They police themselves through criticism and self-criticism. They were helped to restore their self-dignity. The new socialist society ensured the eradication of poverty that drove people into addiction and drug trade.

Small-time drug dealers who pledged to get out of and helped wipe out the drug trade were not considered enemies. The Mao government offered a one-time-only deal to buy out all the products of the small dealers and opium growers to be destroyed. Opium growers were requested to plant rice or wheat instead. Those who refused were arrested and put under surveillance or jailed for re-education.

Liberated from the drug scourge, they were encouraged to join the struggle against drugs and the building of the new socialist society.

Unrepentant big-time drug dealers who enriched themselves off the suffering of the people were classified as enemies of the people. They were sentenced to life imprisonment or execution depending on the gravity of the offense.

According to the New China News Agency (Xinhua) the drug problem In Northern China which had been liberated first was “fundamentally wiped out” by end of 1951. That of Southern China, where opium grew profusely, followed suit after about a year. For over 20 years thereafter, China had almost no drug addiction.

However, after the death of Mao in 1976 and the restoration of capitalism in China ushered in the resurgence of drug trade and addiction. In 2015, over 14 million Chinese were addicted to drugs, as related to Xinhua by the vice president of China’s National Narcotics Control Commission.#

Duterte’s Drug War: Via Body Count or the People’s Movement

The New People’s Army Fight vs Drugs