“My Soldiers”, the Duterte regime’s backbone

Here is an initial list of ex-military and police officials in the civilian bureaucracy—from the Cabinet to the major attached agencies, and in government-owned corporations—proof that indeed Pres. Rodrigo Duterte has militarized the civilian bureaucracy.

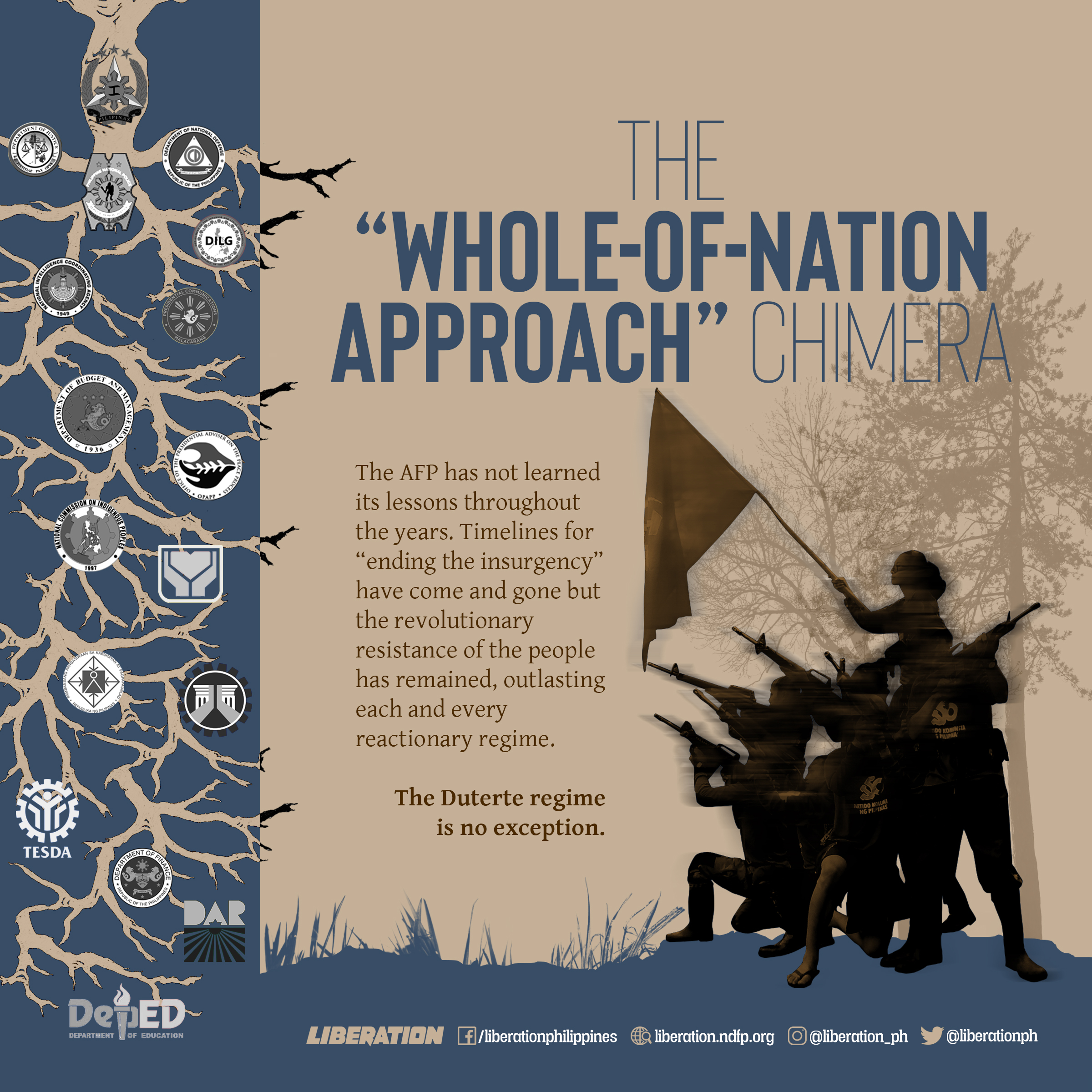

Duterte’s penchant for favouring the military and police has nothing to do with the soldiers’ so-called obedience and efficiency, as he claimed. Terribly scared to get ousted, Duterte had to accord the armed forces with power, status, and resources to secure their loyalty. More importantly, the militarization of the bureaucracy is part of the regime’s counterinsurgency program, the whole-of-nation approach (WONA), a concept that has failed in the previous regimes but, which the Duterte regime is trying hard to bring back to life by posting ex-military and police officials in key government positions.

“To serve as an “efficient mechanism and structure” for implementing the WONA, the National Task Force (NTF) was created, headed by President Duterte as chair, with his national security adviser (Hermogenes Esperon Jr.) as vice-chair. NTF members are ranking officials of the following departments: Internal and Local Government, Justice, National Defense, Public Works, Budget, Finance, Agrarian Reform, Social Welfare, Education, Economic Development, Intelligence, TESDA, Presidential Adviser for the Peace Process; plus the presidential assistant for indigenous peoples concerns, NCIP chair, AFP chief, PNP chief, PCOO secretary and two private sector representatives.”

To date, there are seven department secretaries, six officials with Cabinet-level rank, 28 department undersecretaries and assistant secretaries, and 25 officials of attached agencies who were officials of the Armed Forces of the Philippines and the Philippine National Police.

Also, notable in this list are the “recycled” presidential appointees who were transferred from one agency to another even as they were involved in scandals, mainly corruption cases. Pres. Duterte can’t seem to let go of them. Among his obvious favourites were Isidro Lapeña, Allen Capuyan, and Nicanor Faeldon—who currently does not hold any government position, not yet.

There are also a number of appointees who came from Davao or those assigned in Davao City while Duterte was mayor. And, there are the Gloria Arroyo men—seven AFP and police officers associated with Gloria Arroyo are also in the Duterte administration: Hermogenes Esperon Jr, Eduardo Año, Roy Cimatu, Allen Capuyan (all four remain highly influential and dominant in the Duterte regime), Rodolfo “Garic” J. Garcia, Roberto Lastimoso, and Reynaldo Berroya (all three are in a government-owned corporation).

Also included in this list, although unnumbered, are some of the names of previous appointees who resigned or were reassigned. The list could go over a hundred names more if those in the regional offices and positions lower than those in this list are included; and those who were earlier appointed but were replaced but information on their subsequent assignments is not available.

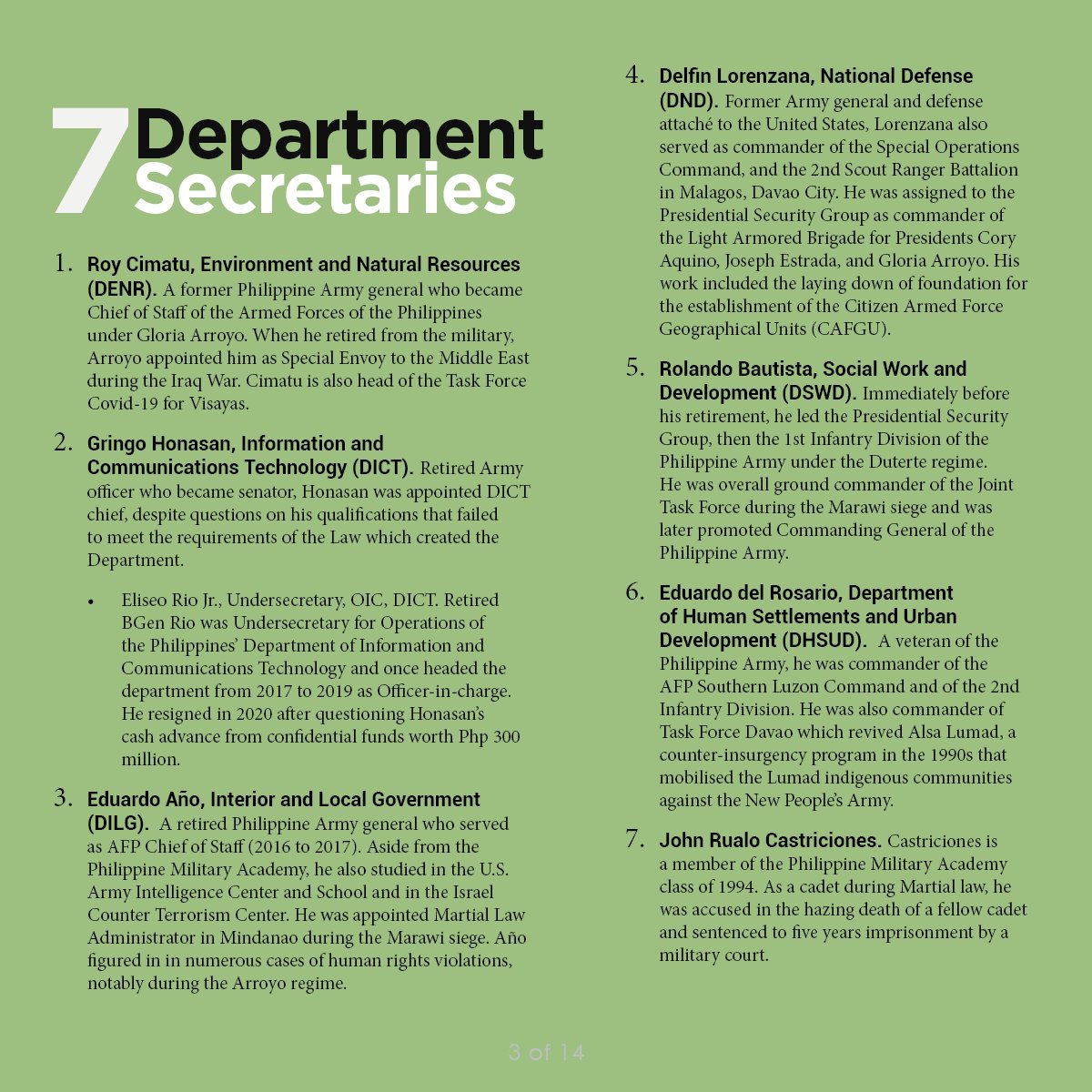

Department Secretaries (7)

1. Roy Cimatu, Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). A former Philippine Army general who became Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces of the Philippines under Gloria Arroyo. When he retired from the military, Arroyo appointed him as Special Envoy to the Middle East during the Iraq War. Cimatu is also head of the Task Force Covid-19 for Visayas.

2. Gringo Honasan, Information and Communications Technology (DICT). Retired Army officer who became senator, Honasan was appointed DICT chief, despite questions on his qualifications that failed to meet the requirements of the Law which created the Department.

· Eliseo Rio Jr., Undersecretary, OIC, DICT. Retired BGen Rio was Undersecretary for Operations of the Philippines’ Department of Information and Communications Technology and once headed the department from 2017 to 2019 as Officer-in-charge. He resigned in 2020 after questioning Honasan’s cash advance from confidential funds worth Php 300 million.

3. Eduardo Año, Interior and Local Government (DILG). A retired Philippine Army general who served as AFP Chief of Staff (2016 to 2017). Aside from the Philippine Military Academy, he also studied in the U.S. Army Intelligence Center and School and in the Israel Counter Terrorism Center. He was appointed Martial Law Administrator in Mindanao during the Marawi siege. Año figured in in numerous cases of human rights violations, notably during the Arroyo regime.

4. Delfin Lorenzana, National Defense (DND). Former Army general and defense attaché to the United States, Lorenzana also served as commander of the Special Operations Command, and the 2nd Scout Ranger Battalion in Malagos, Davao City. He was assigned to the Presidential Security Group as commander of the Light Armored Brigade for Presidents Cory Aquino, Joseph Estrada, and Gloria Arroyo. His work included the laying down of foundation for the establishment of the Citizen Armed Force Geographical Units (CAFGU).

5. Rolando Bautista, Social Work and Development (DSWD). Immediately before his retirement, he led the Presidential Security Group, then the 1st Infantry Division of the Philippine Army under the Duterte regime. He was overall ground commander of the Joint Task Force during the Marawi siege and was later promoted Commanding General of the Philippine Army.

6. Eduardo del Rosario, Department of Human Settlements and Urban Development (DHSUD). A veteran of the Philippine Army, he was commander of the AFP Southern Luzon Command and of the 2nd Infantry Division. He was also commander of Task Force Davao which revived Alsa Lumad, a counter-insurgency program in the 1990s that mobilised the Lumad indigenous communities against the New People’s Army.

7. John Rualo Castriciones. Castriciones is a member of the Philippine Military Academy class of 1994. As a cadet during Martial law, he was accused in the hazing death of a fellow cadet and sentenced to five years imprisonment by a military court.

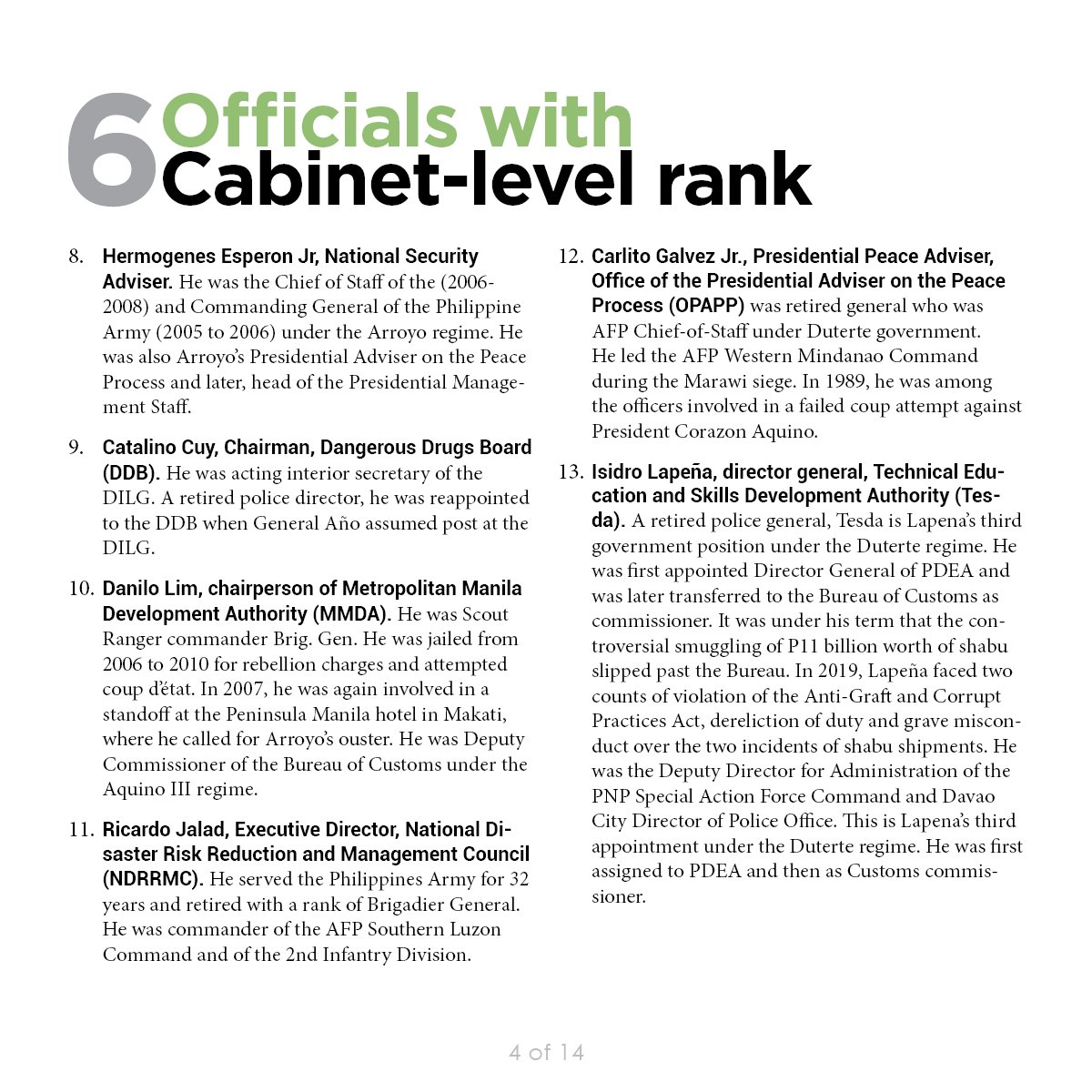

Officials with Cabinet-level rank (6)

8. Hermogenes Esperon Jr, National Security Adviser. He was the Chief of Staff of the (2006-2008) and Commanding General of the Philippine Army (2005 to 2006) under the Arroyo regime. He was also Arroyo’s Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process and later, head of the Presidential Management Staff.

9. Catalino Cuy, Chairman, Dangerous Drugs Board (DDB). He was acting interior secretary of the DILG. A retired police director, he was reappointed to the DDB when General Año assumed post at the DILG.

10. Danilo Lim, chairperson of Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA). He was Scout Ranger commander Brig. Gen. He was jailed from 2006 to 2010 for rebellion charges and attempted coup d’état. In 2007, he was again involved in a standoff at the Peninsula Manila hotel in Makati, where he called for Arroyo’s ouster. He was Deputy Commissioner of the Bureau of Customs under the Aquino III regime.

11. Ricardo Jalad, Executive Director, National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC). He served the Philippines Army for 32 years and retired with a rank of Brigadier General. He was commander of the AFP Southern Luzon Command and of the 2nd Infantry Division.

12. Carlito Galvez Jr., Presidential Peace Adviser, Office of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process (OPAPP) was retired general who was AFP Chief-of-Staff under Duterte government. He led the AFP Western Mindanao Command during the Marawi siege. In 1989, he was among the officers involved in a failed coup attempt against President Corazon Aquino.

13. Isidro Lapeña, director general, Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (Tesda). A retired police general, Tesda is Lapena’s third government position under the Duterte regime. He was first appointed Director General of PDEA and was later transferred to the Bureau of Customs as commissioner. It was under his term that the controversial smuggling of P11 billion worth of shabu slipped past the Bureau. In 2019, Lapeña faced two counts of violation of the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act, dereliction of duty and grave misconduct over the two incidents of shabu shipments. He was the Deputy Director for Administration of the PNP Special Action Force Command and Davao City Director of Police Office. This is Lapena’s third appointment under the Duterte regime. He was first assigned to PDEA and then as Customs commissioner.

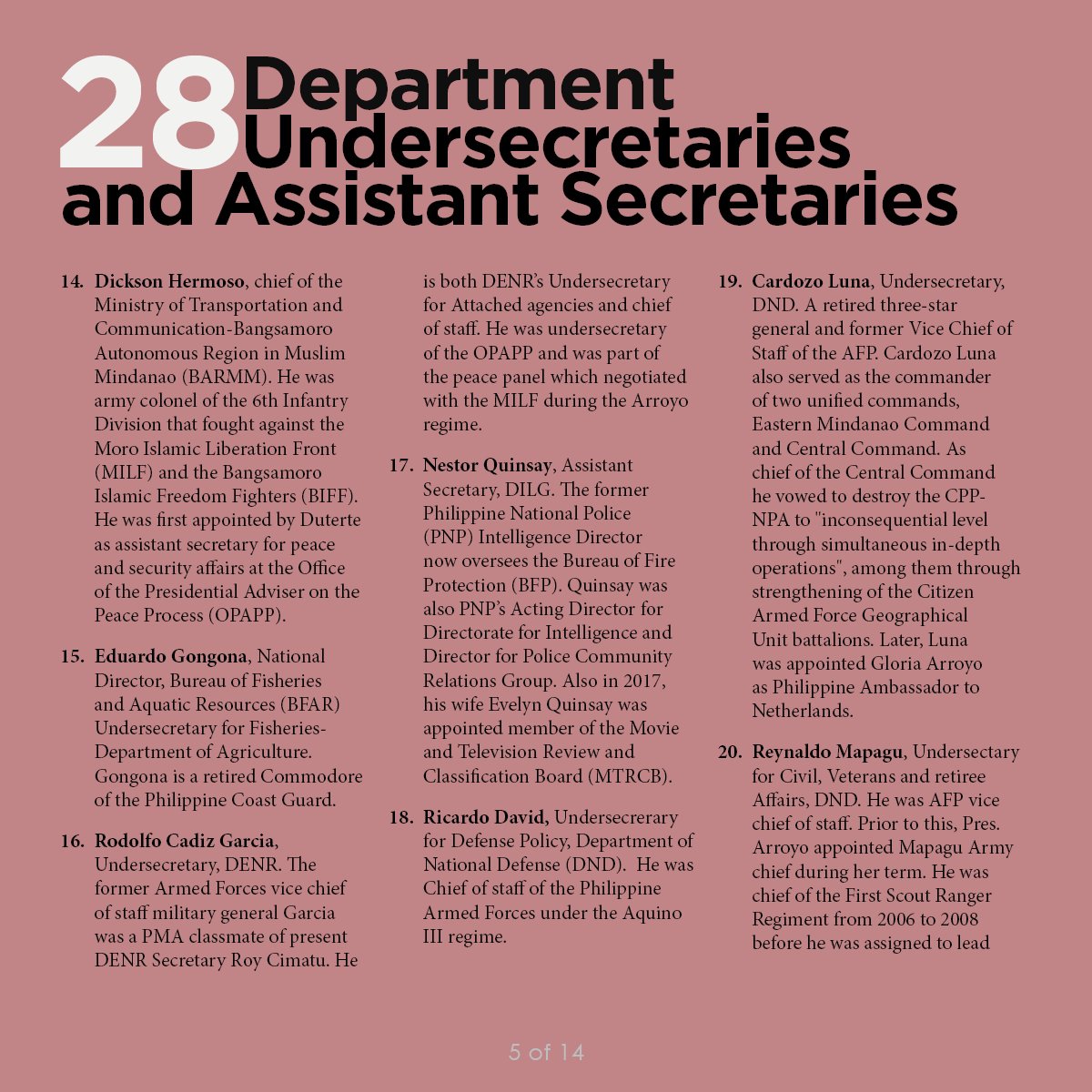

Department Undersecretaries and Assistant Secretaries (28)

14.Dickson Hermoso, chief of the Ministry of Transportation and Communication-Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM). He was army colonel of the 6th Infantry Division that fought against the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) and the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF). He was first appointed by Duterte as assistant secretary for peace and security affairs at the Office of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process (OPAPP).

15. Eduardo Gongona, National Director, Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) Undersecretary for Fisheries-Department of Agriculture. Gongona is a retired Commodore of the Philippine Coast Guard.

16. Rodolfo Cadiz Garcia, Undersecretary, DENR. The former Armed Forces vice chief of staff military general Garcia was a PMA classmate of present DENR Secretary Roy Cimatu. He is both DENR’s Undersecretary for Attached agencies and chief of staff. He was undersecretary of the OPAPP and was part of the peace panel which negotiated with the MILF during the Arroyo regime.

17. Nestor Quinsay, Assistant Secretary, DILG. The former Philippine National Police (PNP) Intelligence Director now oversees the Bureau of Fire Protection (BFP). Quinsay was also PNP’s Acting Director for Directorate for Intelligence and Director for Police Community Relations Group. Also in 2017, his wife Evelyn Quinsay was appointed member of the Movie and Television Review and Classification Board (MTRCB).

18. Ricardo David, Undersecrerary for Defense Policy, Department of National Defense (DND). He was Chief of staff of the Philippine Armed Forces under the Aquino III regime.

19. Cardozo Luna, Undersecretary, DND. A retired three-star general and former Vice Chief of Staff of the AFP. Cardozo Luna also served as the commander of two unified commands, Eastern Mindanao Command and Central Command. As chief of the Central Command he vowed to destroy the CPP-NPA to “inconsequential level through simultaneous in-depth operations”, among them through strengthening of the Citizen Armed Force Geographical Unit battalions. Later, Luna was appointed Gloria Arroyo as Philippine Ambassador to Netherlands.

20. Reynaldo Mapagu, Undersectary for Civil, Veterans and retiree Affairs, DND. He was AFP vice chief of staff. Prior to this, Pres. Arroyo appointed Mapagu Army chief during her term. He was chief of the First Scout Ranger Regiment from 2006 to 2008 before he was assigned to lead the Army’s 10th Infantry Division in Davao and then the National Capital Region Command.

21. Raymundo Elefante, Undersecretary for Finance and Materiel, DND. Elefante was commander of the Air Force Reserve Command (AFRC).

22. Cesar Yano, Undersecretary for Defense Operations, DND. Retired Brig. Gen. Cesar B. Yano was in military service for 34 years. He was assistant chief of staff for civil military operations and spokesman of the 4th Infantry Division Mindanao. He was also chief of staff of the 7th Infantry Division and the Northern Luzon Command. He is the younger brother of Alexander Yano, Arroyo’s former AFP chief of staff who was later appointed ambassador to Brunei.

23. Daniel Casabar, Director, Government Arsenal, DND. He was commander of the Army’s elite units. Retired Maj. Gen. Daniel Casabar headed the Special Operations Command.

24. Arnel Duco, Undersecretary for special concerns (legislative matters), DND. He was AFP Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel. In 2016, BGen. Arnel M Duco was senior military aide to the defense secretary Lorenzana.

25. Ricardo Jalad, Undersecreatary, Administrator of Office of Civil Defense, Executive Director of the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC)-DND. Retired BGen. Jalad served the Philippine Army for 32 years. He was Assistant Division Commander of the 5th ID-PA, among his other assignments. He also served as Brigade Commander of the 2nd Mechanized Infantry Brigade, Chief of the Unified Command Staff of the Southern Luzon Command, among others.

26. Josue S. Garveza Jr, Assistant Secretary for Financial Management, DND. He was commanding officer of the 9th Infantry Division of the Philippine Army during the Aquino III regime. He was later forced to retire under the attrition law.

27. Teodoro Cirilo Torralba III, Assistant Secretary for Assessments and International Affairs, DND. The Brigadier General was military adviser at the Office of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process (OPAPP) when he presided over the court martial proceedings in the trial of four army officers in a botched Basilan operation that killed 19 soldiers.

28. Antonio Bautista, Assistant Secretary for Human Resource, DND. He was AFP deputy chief of staff for reservists and retirees affairs during the Arroyo regime.

29. Manuel Felino V. Ramos, Assistant Secretary for Installations and Self-Reliant Defense Posture, DND. He was a Colonel of the Philippine Army.

30. Angelito M. De Leon, Assistant Secretary for Plans and Programs, DND. He was commander of the7th Infantry Division of the Philippine Army based in Fort Magsaysay. He was also AFP Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations (J3) and Chief of the AFP Command Center.

31. James A. Layug, Director at the Office of Assistant Secretary for Installations and Self-Reliant Defense Posture, DND. He was first appointed Director of Port Operations Service, AOCG and Chief of the Anti-Smuggling Unit of the Office of the Commissioner at the Bureau of Customs. He was a Lieutenant Senior Grade in the Philippine Navy AFP.

32.Jesus Rey Avilla, Assistant Secretary for Logistics and Acquisitions, DND. He was Deputy Inspector General of the AFP.

33. Ernesto Carolina, Undersecretary, Administrator of the Philippine Veterans Affair Office (PVAO)-DND. Lt. Gen. Carolina held, among others, the following posts in the AFP: Commander, 78th Infantry Battalion, Philippine Army (PA); Chief, AFP Liaison Office for Legislative Affairs; Chief of Staff, 4th Infantry Division, PA; Commander of the 401st Infantry Brigade, PA; Commanding General of the 7th Infantry Division, PA; Commander, Southern Luzon Command (SOLCOM); Commander, Southern Command (SOUTHCOM), AFP in Mindanao; and The Deputy Chief of Staff, AFP.

34. Raul Z. Caballes, Assistant Secretary, Deputy Administrator of the Philippine Veterans Affairs Office (PVAO)-DND. MGen. Caballes was AFP Deputy Chief of Staff for Communication, Electronics, and Information Systems (2005- 2007).

35. Manuel Antonio L. Tamayo, Alternate Chairperson of the Civil Aviation of the Philippines (CAAP) Board; Undersecretaty for Aviation & Airports, Department of Transporation (DOTR). He was Chief of Intelligence President Security Group (1988) and Deputy Chief Intelligence of the (1986) when he was also Presidential Escort to President Corazon C. Aquino to the USA.

36. Manuel S. Gonzales, Assistant Secretary for Special Concerns, DOTR. From 2013-2014, BGen. Gonzales was commander of the AFP Joint Task Force in the National Capital Region assigned to combat “terrorism” in Metro Manila.

37. Fidel Igmedio T. Cruz, Jr. Assistant Secretary for Railways, DOTR. BGen. Cruz served as Deputy Commander of the 355th Aviation Engineering Wind of the Philippine Air Force (PAF). In 2013, he led an all-PAF Philippine contingent to Liberia to assist in the “maintenance of law and order.

38. Edgar Galvante, Assistant Secretary, Chief of Land Transportation Office (LTO)-DOTR.

Galvante is a retired police director-general who was deputy chief for operations and director for the NCR Police Office. Galvante is a permanent member of the Dangerous Drugs Board.

39. Rene Glen Paje, Undersecretary, Department of Social Work and Development (DSWD). The retired major general led the First Scout Ranger Regiment during the Marawi siege. The current DSWD secretary Rolando Bautista was Paje’s Army commander.

40. Emmanuel Bautista, Undersecretary and Executive Director of the Security, Justice and Peace Cluster-Office of the President (OP). He was AFP chief of staff before his appointment as Undersecretary at the Office of the President. He headed the National Task Force on the Whole of Nation Initiative and was also the executive Director of the National Task Force on the West Philippine Sea.

41. Arthur Tabaquero, Undersecretary, Presidential Adviser on Military Affairs, OP. He served as commander of the AFP East Mindanao Command. He was also commander of the 8th Infantry Division in Leyte and a short stint in the National Capital Region Command. Tabaquero is from PMA Class of 1978, the adopted class of Gloria Arroyo.

Officials of Attached Agencies (25)

42. Rey Leonardo Guerrero, Commissioner, Bureau of Customs (BOC). The retired Army general was AFP Chief of Staff. He was also commander of the Task Force Davao. He was previously appointed administrator of the Maritime Industry Authority (MARINA) from April to October 2018. He is the third BOC commissioner under the Duterte regime. Previous BOC chief were former AFP officers Nicanor Faeldon and Isidro Lapeña were involved in a drug smuggling controversy at the Bureau. After BOC, Faeldon was transferred to the Office of Civil Defense-DND and later to the Bureau of Corrections. Currently, he no longer holds any government post. Yet.

43. Raniel Ramiro, Deputy Commissioner for Intelligence, (BOC). Former BGen Ramiro was already acting head of the Customs’ Intelligence Group before his formal appointment in 2019. He was AFP-Peace Process Office Chief who, in 2018, initiated the formation of the Peace and Development Forces (PDF) to members of the Cordillera Bodong Administration-Cordillera People’s Liberation Army, former rebels who surrendered and have long been part of the government’s paramilitary group.

44. Donato San Juan, Deputy Commissioner for Internal Administration Group (IAG) BOC. San Juan was the 57th superintendent of PMA and served in different command positions in the AFP.

45. Jessie Cardona, Director III, BOC. The former PNP senior superintendent was officer-in-charge of the Ilocos Sur Police Provincial Office. He was also part of the Anti-Terrorism Council Program Management Center as the new head of the Bureau accreditation office (AMO).

46. Gerald Bantag, Bureau of Corrections-Department of Justice (DOJ). Bantag was an enlisted man of the Philippine Marines Corps. He was the director of the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP) in MIMAROPA. He is the 3rd BuCor chief under the Duterte regime. Army official Nicanor Faeldon and PNP chief Ronald Bato de la Rosa previously held the post.

47. Jaime Morente, CEO VI, Commissioner, Bureau of Immigration-DOJ. A member of the PMA “Dimalupig” Class of 1981, Commissioner Morente handled various positions in the Philippine National Police and in the Philippine Constabulary. He was Duterte’s police chief in Davao City.

48. Allan Iral, Chief, Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP)-DILG. Iral is a member of the Philippine National Police Academy Sandigan Class of 1994. Iral worked as Davao City Jail chief (2004-2006) and jail chief of Davao Region (2014-2015), the same period that Duterte was City mayor. He became BJMP’s director for operations, for personnel and human resource, and for logistics and was once head of the BJMP Central Visayas.

49. Gerardo Gambala, Director IV Transport Security Oversight and Compliance Service OTS-DOTR. A former Army captain Gambala was among the 20 Magdalo officers brought in to the Burueau of Customs when Faeldon was appointed chief. Gambala was deputy commissioner who was linked to the controversial P6.4-billion shabu smuggled from China. He, and Milo Maestrecampo, also an army official, were reappointed to DOTR when they resigned from the Bureau of Customs.

50. Milo Maestrecampo, Assistant Director, Civil Aviation Authority of the Philippines (CAAP)-DOTR. The former military officer of the Magdalo group was reappointed to the DOTR despite allegations of corruption on the release of a P6.4-billion illegal drug shipment from China. He was Import Assessment Services (IAS) director at Bureau of Customs.

51. Cedrick Train, Security Director IV, Office for Transportation Security-DOTR. Appointed by Duterte in March 2019, Train was police regional director in General Santos City. Train is said to be close to Davao Mayor Sara Duterte-Carpio.

52.Robert Empedrad, Administrator, Maritime Industry Authority (MARINA)-DOTR. Vice Admiral Empedrad was flag officer in command of the Philippine Navy. He was also Chief of Staff of Naval Forces Eastern Mindanao; Director, Naval Operations Center; He was Chairman of Defense Acquisition System Assessment Team (DASAT), in charge of the updates on Navy Ships, including the controversial Frigate Acquisition Project. Empedrad replaced Ronald Joseph Mercado who was involved in the Frigate controversy.

53. Ricardo Banayat, Deputy Director General for Operation, CAAP-DOTR. He was Air Force brigadier general and former Commander of the PAF’s 1st Air Division.

54. Antonio Gardiola Jr. LTFB, member, Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board (LTFRB). A retired police chief superintendent, Gardiola was Bicol police regional director in 2017. In 2016, he headed both the PNP Highway Patrol Group and the Inter-Agency Council on Traffic. He is from PMA Class 1986.

55. Archimedes Viaje, Director IV, President, National Defense College of the Philippines (NDCP)-DND. BGen Viaje was a commission officer in the Philippine Navy. He was part of the Corps of Professors and headed the Command Guidance and Counselling Office of the PMA and later as head of the Department of Social Sciences of the Academic Group. He served as chief of the Military Affairs Division and Chief of Staff of the President of the NDCP.

· Prior to Viaje’s appointment, another retired military officer Roberto Estioko was president of the NDCP. Estioko was AFP vice commander of the Philippine Navy.

· Former AFP-Civil Relations Service chief BGen. Rolando Jungco was previously listed as Executive Vice President of the NDCP although the position is now declared vacant.

56. Casiano Monilla, Assistant Secretary, Civil Defense Deputy Administrator for Operations, OCD-DND. Retired BGen Monilla was Assistant Division Commander, 10th ID-PA.

57. Henry Anthony M. Torres, Director Region 8, Office of the Civil Defense (OCD)-DND. Col. Torres was among the Oakwood mutineers who brought in to the Bureau of Customs in 2017 when Gerardo Gambala became Deputy Commission of BOC’s Management Information System and Technology Group.

58. Allen Capuyan, Executive Director, National Commission on Indigenous Peoples-DSWD. Ret. Col. Capuyan was chief for operations at the Intelligence Service of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (ISAFP) under the Arroyo administration. This is Capuyan’s 4th post under the Duterte regime. He was first assistant general manager for security and emergency services of the Manila International Airport Authority. Implicated in the P6.4-billion shabu smuggling, he was reappointed undersecretary as Presidential Adviser on Indigenous Peoples’ Concerns. In 2019, he was appointed executive director of the National Secretariat of the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC).

59. Alex Monteagudo, Director General, National Intelligence Coordination Agency (NICA)-Office of the President (OP). Monteagudo was police director of the PNP. Among others, he was assigned as Provincial Director of Cotabato, PNP Regional 12 Director, and director of the Directorate for Investigation and Detective Management and later for Operations.

60. Rufino Lopez, Deputy Director General, National Security Council (NSC)-Office of the President (OP). Retired Rear Admiral Rufino Lopez was AFP inspector general. He was chair of the Ad Hoc Committee which was created to investigate a supposed coup against Gloria Arroyo on Feb. 24 and the stand-off at the Marine Headquarters in Fort Bonifacio two days later. Among those investigated were Brig.Gen Danilo Lim, chief of the First Scout Rangers Regiment, Maj. Gen. Renato Miranda, commander of the Philippine Marines, Col. Ariel Querubin, head of the Marines in Lanao province.

61. Vicente M. Agdamag, Deputy Director General, NSC-OP. Retired Rear Admiral Agdamag was commander of the Naval Education and Training Command of the AFP. As director of the NSC, Agdamag is also a member of the NTF-ELCAC.

62. Damian Carlos, Deputy Director General, NSC-OP. Ret. Admiral Carlos was appointed by Gloria Arryo Coast Guard commandant in 2006. Immediately before this appointment he was Coast Guard deputy commandant for administration. His other previous assignments were Coast Guard district commander in Palawan and in the NCR. He also became commander of Coast Guard Operating Forces.

63. Bruce Concepcion, Special Envoy on Transnational Crime, Philippine Center on Transnational Crime (PCTC)-OP. Lt. Colonel Bruce Concepcion became public information officer of the Philippine Air Force. He served the military for 26 years and was awarded, among others, The Outstanding Pilipino Soldier (TOPS) Award. Prior to his current position, he was PCTC chief consultant for the Visayas and Mindanao. He was also a member of the Board of Directors of the Philippine National Oil Company (PNOC).

64. Allan Guisihan, Executive Director, PCTC-OP. In 2010, Guisihan was director of the Negros Occidental Provincial Police Office (NOPPO) who was under investigation for his alleged involvement in illegal mining activities in Iloilo when he was promoted officer-in-charge of the Region 6 Police Office. He became part of its directorial staff, the fourth highest position in PNP-Western Visayas.

65. Wilkins Villanueva, Director General, Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA). Duterte appointed Villanueva in May 2020 to replace Aaron Aquino who was reassigned as president and CEO of the Clark International Airport Corp. (Ciac). Villanueva was among those who crafted the anti-drug programs of the PDEA and the PNP, including “Oplan Tokhang.” He headed PDEA’s Northern Mindanao office prior to this appointment. Villanueva is the third PDEA director general under the Duterte regime. The first two were Isidro Lapeña and Aaron Aquino. Aquino is now president and chief executive officer (CEO) of the Clark International Airport Corp.

66. Gregorio Pimentel, Deputy Director General, PDEA. Pimentel was head of the Directorate for Intelligence of the PNP. He replaced Jesus Fajardo who joined former PDEA director general Isidro Lapeña at the Bureau of Customs in 2018. He was also head of the PNP Highway Patrol Group in the Davao region.

· Retired Major General Jesus Fajardo was chief of the 2nd Air Division of the Philippine Air Force. He is a member of the PMA Class 1978. From BOC, MGen. Fajardo was later transferred to TESDA as Region 3 Director when Lapeña was reassigned to TESDA.

Officers in Government-owned and Controlled Corporations (22)

67. Ferdinand Golez, Director, Bases Conversion and Development Authority (BCDA). Retired Vice Admiral Golez has been with the BCDA since 2011. He was appointed by Gloria Arroyo Flag Officer-in-Command of the Philippine Navy from 2008-2010. Golez was also commander of the Naval Education and Training Command based in Zambales. Golez is from PMA Class 1976, a batchmate of AFP Chief of Staff Alexander Yano and Army Chief Lt. Gen. Victor Ibrado. He is the brother of Roilo Golez.

68. Glorioso Miranda, Director, BCDA. Lt. Gen. Miranda was commanding general of the Philippine Army. He served both as acting chief of staff and vice chief of staff of the AFP. He became chief of the Northern Luzon Command and the 7th Infantry Division-PA, among other commands.

69. Benjamin Defensor, Director, Clark Development Corporation (CDC). General Defensor was the 26th Commanding General of the Philippine Air Force and the 30th Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces of the Philippines.

70. Aaron Aquino, President and Chief Executive Officer, Clark International Airport Corp. (CIAC). Retired Police chief superintendent was reassigned by Duterte to CIAC on May 2020 leaving his post as PDEA director general. This is Aquino’s second post under the Duterte regime. Aquino was in the Presidential Security Group (PSG) during the presidency of Corazon Aquino and Fidel Ramos. He was chief of the Police Regional 3 Office. He was part of “Oplan Double Barrel”—Duterte’s so-called war on drugs.

71. Eduardo Davalan, Director, John Hay Management Corporation (JHMC). Retired BGen. Davalan was regiment commander of the First Scout Ranger Regiment-Philippine Army. Among his previous military assignments were: 7th and 10th ID-PA; Commander in Northern Luzon, Scout Ranger Training School; Security Officer Chief JUSMAG; Head Department of Ground Warfare at the Philippine Military Academy.

72. Miguel dela Cruz Abaya, Director, Development Bank of the Philippines (DBP). Abaya was Regional Commander of the Philippine Constabulary-Integrated National Police (PC-INP). He represents the military and police institutions in the DBP Board. DBP provides finance facilities for the AFP-PNP modernization programs.

73. Alan Luga, Trustee, Government Service Insurance System (GSIS). Lt. Gen. Luga was Vice Chief of Staff of the AFP. He served as Commander of the AFP Southern Luzon Command. He previously headed the 802nd and 1001st Infantry Brigade and the 7th Infantry Division of the Philippine Army. He was a member of the GRP Peace Panel for the GRP-MILF Peace Talks as the Chairman of the ADHOC Joint Action Group, OPAPP. Currently, he also heads the AFP General Insurance Corporation.

74. Reynaldo Berroya, Administrator, Light Rail Transit Administration (LRTA). Retired police general Berroya was appointed by Gloria Arroyo PNP intelligence chief and later regional director of the Central Luzon police then as director of the PNP Civil Security Group based in Camp Crame. He was a friend of then Vice President Joseph Estrada who brought Berroya into the anti-kidnapping group headed by Estrada. Berroyo was found guilty and sentenced to jail in 1995 for his involvement in the May 11, 1993 kidnapping of Taiwanese national Jack Chou.

· Former general Danilo Lim also sits as Board Member of LRTA in his capacity as chairperson of the Metro Manila Development Authority.

75. Rodolfo “Garic” Jasminez Garcia, General Manager, MRT3 DOTR. Garcia, a retired police general, was chief of PNP Intelligence Group during the presidency of Fidel Ramos. Pres. Arroyo appointed him chief of PNP Region 12 and later as MRT Director for Operations, the same time Arroyo appointed Reynaldo Berroya general manager of MRT 3. Garcia and Berroya were classmates at the PMA.

76. Ricardo Visaya, Administrator, National Irrigation Administration (NIA). He was AFP chief of staff. He was assistant division commander of 6th Infantry Division and former commander of the 4th Infantry Division before he headed the Southern Luzon Command.

77. Abraham Bagasin, Senior Deputy Administrator, NIA. BGen. Bagasin was AFP chief of staff. He became commander of the 11th Infantry Battalion in Negros Island and of the First Scout Ranger Regiment. Prior to his appointment to NIA, Duterte appointed him director of the John Hay Management Corporation.

78. Romeo Gan, Deputy Administrator for Administrative and Finance Sector (NIA). MGen. Gan was Commander of the 2ID “Jungle Fighter” Division of the Philippine Army. He became Assistant Division Commander of the 6th ID based in Maguindanao before he was appointed civil relations chief. Generals Gan, Visaya, and Bagasin belong to the same PMA class 1983.

79. Anselmo Simeon Pinili, Chairperson, Philippine Charity Sweepstakes Office (PCSO). Retired police general Anselmo Pinili replaced former PCSO Chair Jose Jorge Corpuz who resigned for “health reasons” in 2018. Pinili was Special Envoy on Transnational Crime until 2018; and Deputy Regional Director for Administration at the Police Region 11 office. Pinili batted for a localized “peace talks” between the government and the revolutionary forces in Davao del Norte and Compostela Valley. In May 2019, graft complaints were filed at the Ombudsman against Pinili and other PCSO officials.

· Jose Jorge Corpuz, a retired chief superintendent was appointed in 2017 chair of the PCSO. He was the director for Integrated Police Operations for Southern Luzon. He resigned in 2018.

80. Royina Garma, Vice Chairperson and General Manager, PCSO. Garma was Cebu City police chief who was appointed by Duterte in 2019 to replace ex-Marine general Alexander Balutan. Garma, prior to her appointment as Cebu City police chief, was administrative officer and then head of the Davao City’s Women and Children’s Protection Desk. She was also chief of Sasa and Sta. Ana police precincts in Davao City.

· Gen. Balutan was appointed in PCSO in 2016 but he was dismissed because of overspending for the PCSO’s Christmas party and for favoring a certain company for small town lottery operations.

81. Roberto Lastimoso, Chairperson, Philippine National Railways (PNR). Lastimoso was already in various government agencies after his stint as PNP director general. He was general manager of MRT 3 and chief of Land Transportation Office during the Arroyo regime. He was also Vice-Chairman of GRP peace panel with MNLF, Senior Police Assistant of DILG.

82. Michael Mellijor Tulen, Director, PNR. Appointed in November 2016, retired Police Superintendent Tulen is from Tagum City. He headed the Investigation Detective Management Section (IDMS) of the Provincial Police Office in Davao del Norte.

83. Marlene Romero Padua, Director, Health Care Providers Sector Representative, PhilHealth. Retired BGen. Padua served as chief nurse of the 4th Infantry Division-PA, Philippine Navy, and the AFP. Aside from sitting in the Philhealth Board of Directors, she is also currently Chair of the PNP Health Service Advisory Council, PNP Health Service PATROL Plan, Dean of College of Nursing of the Arellano University-Pasig.

· Dante A. Gierran was recently appointed PhilHealth President and CEO after retired Army general Ricardo Morales resigned “for health reasons” amid a string of corruption charges rocked Philhealth. Gierran, technically do not belong the “ex-military and police officials category” as he was Director of the NBI, an attached agency of the Justice Department. He was also acting Region XI director of the NBI in Davao City.

· Ricardo Morales, a retired Army general, was appointed by Duterte in 2019 President and CEO of PhilHealth, a few days after he was placed as member of the MWSS board of trustee. Morales was aide de camp of former first lady Imelda Marcos but at the same time a member of the Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM), who served as the rebel soldiers’ informant in Malacanang. In the succeeding years, he became executive officer at the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff of Plans and then director of the Army Modernization and Strategic Studies Office.

84. Reuben Lista, President and Chief Executive Officer, Philippine National Oil Company (PNOC). Retired Admiral Lista was Commandant of the Philippine Coast Guard (PCG). He held various positions in the Philippine Navy, AFP, and the Philippine Coast Guard. He was commander of Marine Environmental Protection Command, of the 1st Coast Guard District, and the 8th Coast Guard District (Davao), among others. He was also part of the Presidential Security Command (PSC), National Intelligence and Security Authority (NISA) and the Office of the President (OP).

85. Romeo de Vera Poquiz, Director, PNOC. A retired Major General, Poquiz was Commander of the 2nd Air Division, Air Force in the Visayas; Air Force Inspector General; Deputy Commander, 1st Air Division; and Wing Commander, 710th Special Operations Wing, among others. Prior to his appointment to the PNOC, he was director of the Bases Conversion and Development Authority, the Fort Bonifacio Development Corporation, and the Bonifacio Transport Corporation.

86. Adolf Borje, Director, PNOC. Retired Rear Admiral Borje was Commander of Naval Forces South. He became chief of Naval staff and chief of Naval Operations of the Philippine Navy. After retirement he was consultant of Davao City for Public Safety and Welfare. He was also security consultant to various companies such as Apex Mining Corporation, Dole/Stanfilco, Sumifru Philippines Corporation, and Banana Growers and Exporters Association, all based in Davao.

· Current Baguio City Mayor Benjamin Magalong was appointed by Duterte in January 2018 to the PNOC Board of Directors. He was deputy chief for operations of the PNP when he retired. He was chief PNP in the Cordillera region and member of the Directorate for Investigation and Detective Management (DIDM). He was head of the Special Operations Battalion of the Special Action Force. He was also assigned to the PDEA, CIDC and he chaired the PNP Board of Inquiry on the Mamasapano botched military operation.

87. Rozzano Dosado Briguez, President and Chief Executive Officer, PNOC-Exploration Corporation. Retired Lt. Gen. Briguez was Commanding General of the Philippine Air Force. He was also commander of the AFP Western Command. Other positions he held were: commander of Tactical Operations Group 11 of the Tactical Operations Command in Davao, Assistant Chief of Air Staff for Operations, A-3, 250th Presidential Airlift Wing (Deputy Wing Commander).

88. Oscar Rabena, Director, PNOC-Exploration Corporation. He was Commanding General of the Philippine Air Force. Prior to his designation as Air Force Chief, he was Chief Strategic Planner of the AFP as Deputy Chief of Staff for Plans and Programs and Philippine Air Force Inspector General. He became Special Assistant to the Presidential Adviser on Military Affairs and Commander of 18 Assault Squadron.

Diplomatic Mission (1)

89. Eduardo “Red” Kapunan Jr, Ambassador to Myanmar-DFA. Air Force colonel Kapunan was one of the founders of Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM) who was implicated in the murder of labor leader Rolando Olalia and companion Leonor Alay-ay.