Ericson Acosta was a gifted writer and performer who could have landed a comfortable gig on any mainstream publication or production outfit. He was already writing for a major broadsheet—rubbing elbows with rising bands such as the Eraserheads and Yano—when his life would take a detour during the mid-90’s.

Despite the proverbial rock n’roll lifestyle he was enjoying as an up and coming writer, there was still something missing in his life. During his early years in UP, he dabbled in theater productions and became involved in the human rights organization Amnesty International. His life was colorful and somewhat wild. He did not figure in any of the activist organizations like the LFS (League of Filipino Students).

He did however become an editor of the Kultura section of the Philippine Collegian. It is here where he became exposed to UP activists from a cultural group who were about to mount a mini-production.

Ericson would engage with the activists and would find himself helping out in the cultural production and then later, joining discussions and protest actions. It was in the summer of 1995 when he would join a cultural integration in the countryside of Southern Tagalog. There in the peasant communities, his understanding of the problems of society and the need for revolutionary struggle would deepen.

The encounter with the poor peasants and the revolutionary forces who were organizing had such a great impact on Ericson that he returned to Manila a full-time activist. He became even more active in the militant student movement and took on leading roles in various organizations. It was during this time that he would start composing original songs and later on, write an original play for a multi-media production.

Ericson’s early music—heavily influenced by blues, folk and rock—attempted to capture the feel of the times, including the rectification movement that was sweeping the entire mass movement. “Balik aralan ang kasaysayan, iwasto ang pagkakamali” went the song Awit ng Kasaysayan. And as if foreshadowing his transition from student activist to the peasant organizer in the countryside, many of his songs spoke of the decision to embrace the revolutionary struggle full-time. “Ang paalam, ko’y iyong tanggapin, paglisan ko’y iyong salubungin” went the first line of the song “Paalam”.

In his years as a UP activist, Ericson was able to mount plays, compose songs, perform in various gigs, and compile an impressive body of work as a young writer. But it was in the countryside, far from the limelight and literary circles, where his full potential as an artist in the service of the people would be realized.

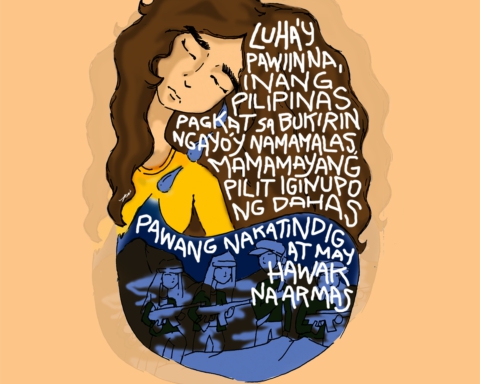

Immersed in the communities of peasants and farm workers, he would create epic songs that highlighted class oppression and resistance. They would mirror the daily struggles of the workers and peasants. Under the nom de guerre Sonya Gerilya, and in collaboration with wife Kerima Tariman who went by the nom de guerre Marijoe Monumento, they released the literary booklet Anahaw. It was a collection of songs and poems of life in the countryside. The song Anahaw told of the various practical uses of the country’s national leaf, from roofing material, fan, head cover, and later on, a means to conceal the guns of the Red fighters. The song Duyan is a metaphor for the distance apart of guerrillas and their loved ones, with a witty reprise of the national anthem’s “duyan ka ng magiting”.

Even the from or style of his songs would evolve and would now be more in line with popularization among the people, even as he sought to raise lyrical and musical standards. Whereas his songs during his UP days would require a degree of technical skill, his later songs would be more “sing-able” for ordinary folk. A still “unreleased” song called Ating Paaralan is literally a PADEPA (Pambansa Democratikong Paaralan) hymn that could be sung before educational discussions are held. “Sa abang barong-barong ni Inay at ni Tatay. Sa lihim na lilim ng punong malabay. Ay laging bukas, bukas na, bukas na ang ating paaralan. Pambansa demokratikong paaralan!”

He would journey with Kerima from the mountains of Bicol region to the rugged hills of Samar, where he would be arrested by the military on trumped-up charges.

It was in prison that Ericson would find a new perspective on waging revolutionary struggle. He needed to fight even behind bars, overcoming the limits of physical confinement through his words and songs. Everyday as he looked out the window of the Calbayog Sub-Provincial Jail, he would see soldiers camped outside the facility. The soldiers were there to make sure he wouldn’t escape. But as in the song “Usok”, where smoke would escape between the steel bars of a prison cell, so did his poetry reach beyond the prison walls.

Ericson’s two years in the Calbayog jail would result in an even more powerful body of work that included “Isang Minutong Katahimikan, Astig, Kosa, Usok, Palad, and what would be the title of his book, Mula Tarima Hanggang.

The song “Palad” tells of the tragic conditions of toilers whose calloused hands would transform into clenched fists and the hands that would take up arms against the oppressor.

Having been released from jail, Ericson would again be part of the legal democratic movement and would maximize the relative freedom he enjoyed to perform, give workshops, write, and most importantly, organize. Upon his release, he rejoined the peasant movement. In his time helping the farm workers of Hacienda Luisita, he would write the song “Sampung Taon”, to mark the 10th year of the Luisita Massacre.

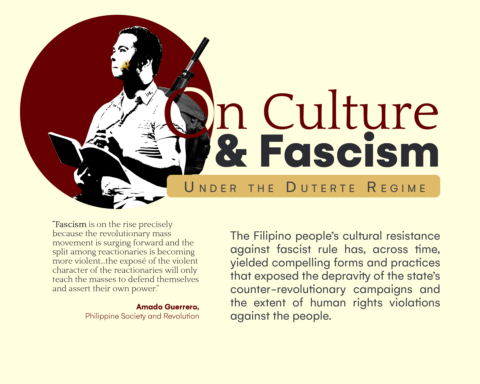

Ericson’s class origin was from the lower petty bourgeoisie but having enormous talent and skill, he could have easily moved up the social ladder. However, throughout his activist life, he sought to remold his outlook to become a proletarian revolutionary. He accomplished this by working and living with the poor peasants of Bicol, Samar, Tarlac and Negros. And it was this period of intense revolutionary struggle that brought out the best in Ericson as an artist for the people.

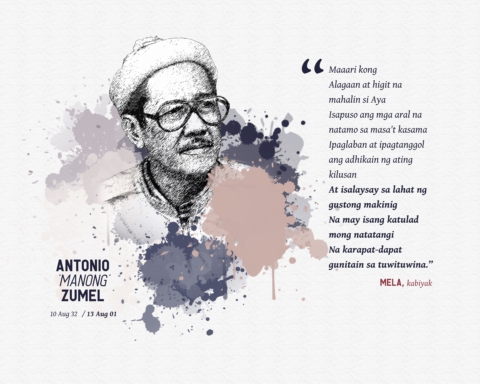

Ericson and Kerima quietly left for Negros Island in 2018 to continue their revolutionary work among the peasant masses and sakadas. Kerima would be martyred in a firefight in August 2021, while Ericson would be summarily executed by the military on November 30, 2022, in Kabankalan, Negros. Their legacy would remain even after their untimely passing, as these reflect not just artistic excellence but more importantly, the great cause of freedom and democracy. (Juan Monumento) ###