Yet Another Turnaround on the Peace Talks

On April 3, speaking at a public gathering in Bongabong, Oriental Mindoro (a known stronghold of the New People’s Army), President Rodrigo Duterte made this unexpected statement:

“I’d like to address myself first to the NPAs (sic). You know, we’re not enemies. Even though I want to fight you, my heart says I could not kill my fellow Filipinos. Let’s talk about peace and stop killing… If you really want to negotiate with us, you stop immediately. You and I will have a ceasefire.”

“I want to pursue the peace talks with you,” he added, with this caution, “But along the way, there will be many obstructions and everything… You must understand that it won’t be easy for us.”

A sober statement, a welco

me departure from the usually bilious outbursts one was prone to expect from the volatile mayor-turned president.

The following day, Duterte directed his Cabinet, specifically his peace adviser Jesus Dureza, to work on resuming the GRP-NDFP peace negotiations he had repeatedly cancelled. “Let’s give this another last chance,” he said. He set a two-month period for the two parties to clear the way for the start of formal peace negotiations.

This is yet another Duterte turnaround on his stance vis-à-vis the peace talks and the revolutionary movement in over a year. Recall that after unraveling himself as a fascist he addressed the revolutionary forces—with whom he had avowed a long-running friendship—and curtly declared: “I am your enemy!” Thereafter he showed both in words and actions that he meant what he said.

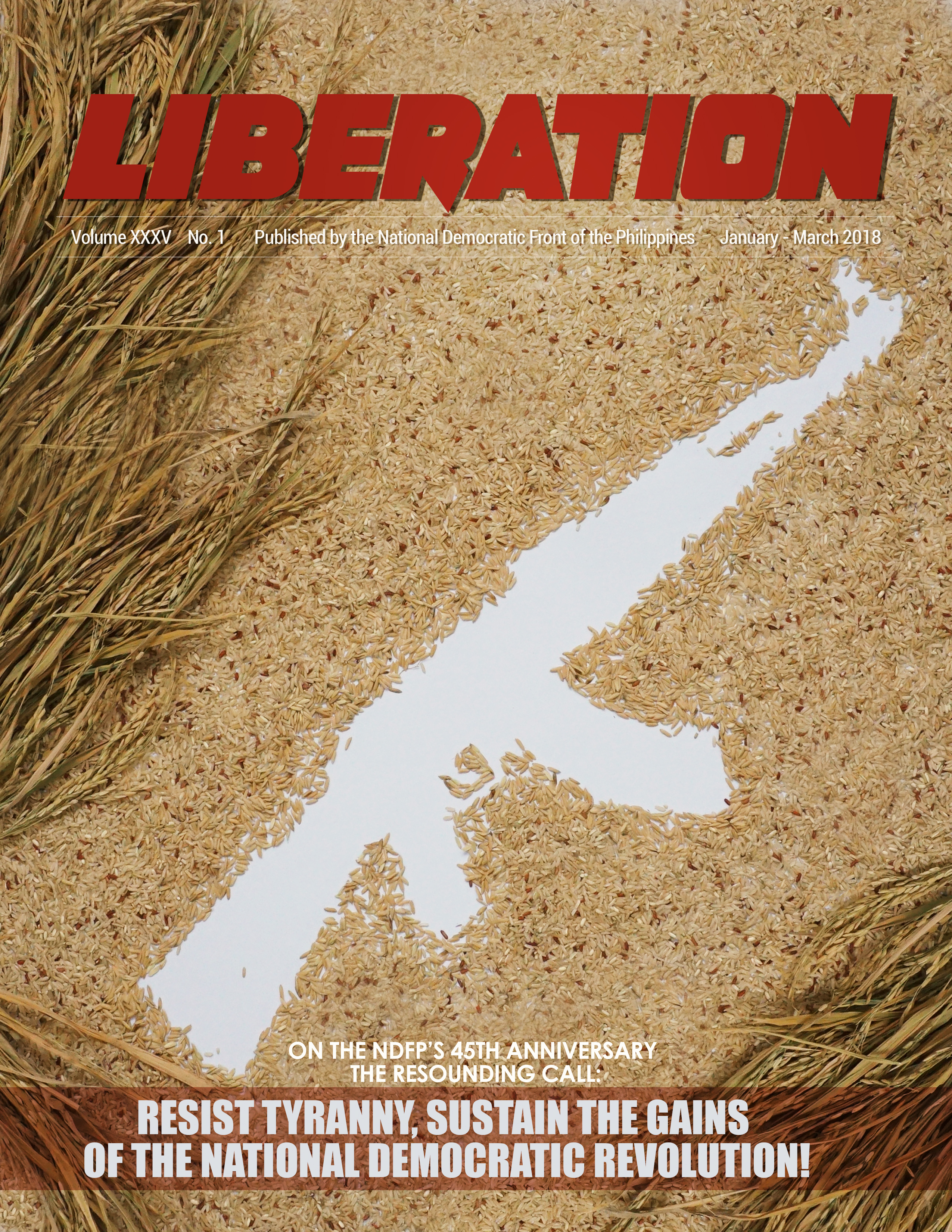

Besides aggressively pursuing an “all-out war” against the CPP-NPA since February 2017 and ordering the AFP to use all its war assets to “flatten the hills,” Duterte issued two presidential edicts: one “terminating” the GRP-NDFP peace talks (Proclamation 360, on November 23) and another declaring the Communist Party of the Philippines and the New People’s Army as “terrorist organizations” (Proclamation 374, on December 5).

Again to show he meant business, Duterte directed his corrupt and incompetent department of justice (DoJ) to secure judicial imprimatur for Proclamation 374, as required by the anti-terrorism law (oddly titled as the Human Security Act of 2007). On February 23 the DoJ filed a “petition for proscription,” asking a regional trial court in Manila to declare the CPP and the NPA as “terrorist and outlawed organizations, associations and/or group of persons.”

The petition cites the CPP and the NPA as respondents in the civil procedure specified by the law. However, it includes a list of 470 names and 187 aliases of individuals who it alleges to be “known officers and members” of the CPP-NPA. The listing implies that should the court declare the two organizations as terrorists, those named in the list would similarly be tagged and hounded as terrorists, stripped of their rights and freedoms.

According to the Public Interest Law Center, the Human Security Act treats suspected and judicially-declared terrorists alike. For instance, “both are sanctioned with surveillance, interception and recording of conversations, prolonged arbitrary detention, and examination of bank accounts.”

The list includes the names of five members of the NDFP negotiating panel, 30 NDFP consultants and one independent cooperator, at least 50 human rights defenders (including the United Nations special rapporteur on indigenous peoples), leaders of people’s organizations and activists, 20 peasant leaders, and 16 political detainees.

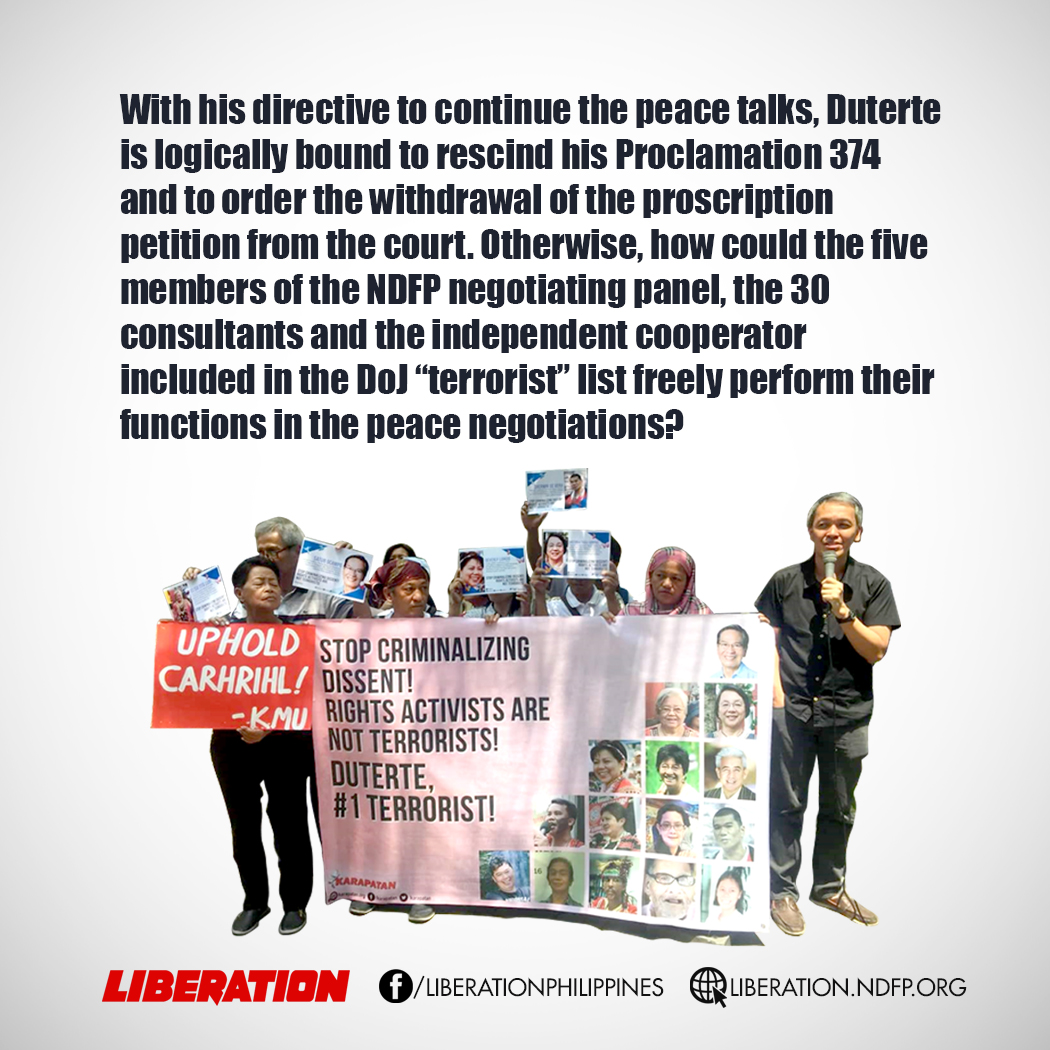

With his directive to continue the peace talks, Duterte is logically bound to rescind his Proclamation 374 and to order the withdrawal of the proscription petition from the court. Otherwise, how could the five members of the NDFP negotiating panel, the 30 consultants and the independent cooperator included in the DoJ “terrorist” list freely perform their functions in the peace negotiations?

But No! His senior deputy executive secretary Menardo Guevarra—who he has named to replace dismissed DoJ secretary Vitaliano Aguirre II—said the government would not withdraw the petition. Peace adviser Dureza echoed that line, but could not clearly explain why.

In a television interview, Dureza said: “My understanding is, when the talks were cancelled, [Proclamation 374] was a necessary step that government had to pursue. But (we) had to file a petition in court… and it’s pending there. There are no efforts to withdraw it.” He added, “We’d like to meet with (the NDFP panel) across the table first and find out how to deal with this [issue].”

NDFP chief political consultant Jose Ma. Sison has appropriately called on Duterte to rescind both Proclamations 360 and 374 to provide a conducive atmosphere for continuing the peace talks.

However, Duterte has not said anything about this matter. One is drawn into assuming that he wants to hold his proclamation and the proscription petition as a Damocles sword over the heads of the NDFP negotiating panel, which is not conducive to peace negotiations.

Duterte can ensure the success of his “last-chance” pursuit of the peace talks by withdrawing the proscription petition. Failing that, the issue will be resolved by the court. A move towards such a resolution was recently taken through a motion to dismiss the DoJ petition for lack of merit.

On March 19, the Public Interest Law Center (PILC), filed the motion to dismiss in behalf of Saturnino C. Ocampo, the independent cooperator invited by the NDFP panel to help in the peace talks. His name is listed in the DoJ petition among those it claims to be “known officers” of the CPP-NPA with known addresses through whom the respondents CPP and NPA “may be served with summons…” In the summons given to him, the court asked Ocampo to answer the allegations in the petition within 15 days.

Filing the motion to dismiss through the PILC was Ocampo’s way of complying with the summons. He puts forward two arguments: 1) Since the petition does not cite him as a respondent and does not show a cause for action against him, there is no valid basis for the court to acquire jurisdiction over his person. 2) The petition, despite its numerous documentary attachments, fails to present sufficient and convincing proof as required by the Human Security Act, on the basis of which the court can validly declare the CPP and the NPA as terrorist organizations. Therefore the court must dismiss the petition.

At the hearing on the motion to dismiss, on March 23, no DoJ prosecutor appeared before the court, which may indicate a lack of interest or resolve to pursue its petition. The court thus ordered the DoJ to submit a written reply to the motion within 15 days, after which it may either rule on the petition or schedule oral arguments.

Besides this issue, Duterte has set four preconditions that can obstruct the road towards the continuation of the peace negotiations. These are: a ceasefire upfront; “stop attacking my soldiers and policemen;” stop revolutionary taxation; and “don’t demand a coalition government.” Moreover, he has intimated he wants the peace negotiations to be held in the country—not abroad, as has been the agreed arrangement since 1992 to ensure the security of the NDFP panel, consultants, staff and other participants.

Setting such preconditions violates one of the principles set by the Hague Joint Declaration of 1992, which states: “4. The holding of peace negotiations must be in accordance with mutually accepted principles, including national sovereignty, democracy and social justice and no precondition shall be made to negate the inherent character and purpose of the peace negotiations (emphasis ours).”

Nonetheless, with the view of averting another heated confrontation with Duterte, Sison has responded with an amiable stance. He said all these preconditions can be discussed, and probably settled in principle, between the two parties before agreeing to continue the interrupted formal negotiations.

“The important thing,” he pointed out, “is that the principals, namely President Duterte and the National Council of the NDFP, have given the go-signal to their respective negotiating panels to contact each other in preparation for the formal talks.”

Taking the cue from Sison’s stance, Dureza told the media the GRP has opted for a “quiet” approach to the pre-formal negotiations bilateral talks. GRP peace panel head Silvestre Bello III and he are “in a hurry” to meet with their NDFP counterparts, he said, because Duterte had given a two-month deadline.

“It’s going to be quiet talks in the meantime, so that if there is going to be some big result, then that’s the time when we’re gonna disclose it,” he said.

This mutual cool-headed or non-adversarial approach to tackling the abovecited issues—during the preliminary discreet discussions between the two parties—deserve commendation and encouragement by all peace advocacy groups, which commendably have unrelentingly called for the continuation of the GRP-NDFP peace negotiations.

First things to settle: the formal peace negotiations must continue from the status at which Duterte “terminated” them in November 2017; the negotiations must continue in a neutral foreign venue facilitated by the Royal Norwegian Government; and the parties must uphold all previously signed agreements.

It will help, to a considerable degree in enhancing a favorable atmosphere for continuing the peace talks, if the two parties agree to immediately implement the Comprehensive Agreement on Respect for Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law (CARHRIHL). After all, they mutually committed to do so in their joint statement after the fourth round of formal negotiations in April 2017.

More than improving the atmosphere for negotiations and consultations, implementing the CARHRIHL can serve as a veritable test on the sincerity of both sides in carrying out their written commitments.

Over and above that, it will accord justice and provide material compensation to the numerous civilians (individuals, families, communities) who have endured sufferings due to violations of human rights and international humanitarian law, committed by either party, in the course of the almost half a century of internal armed conflict.