The National Minorities and the National Democratic Revolution

By Iliya Makalipay

The national minorities — the Bangsamoro and the various groups of indigenous peoples — currently bear the brunt of the fascist attacks by the US-Duterte regime.

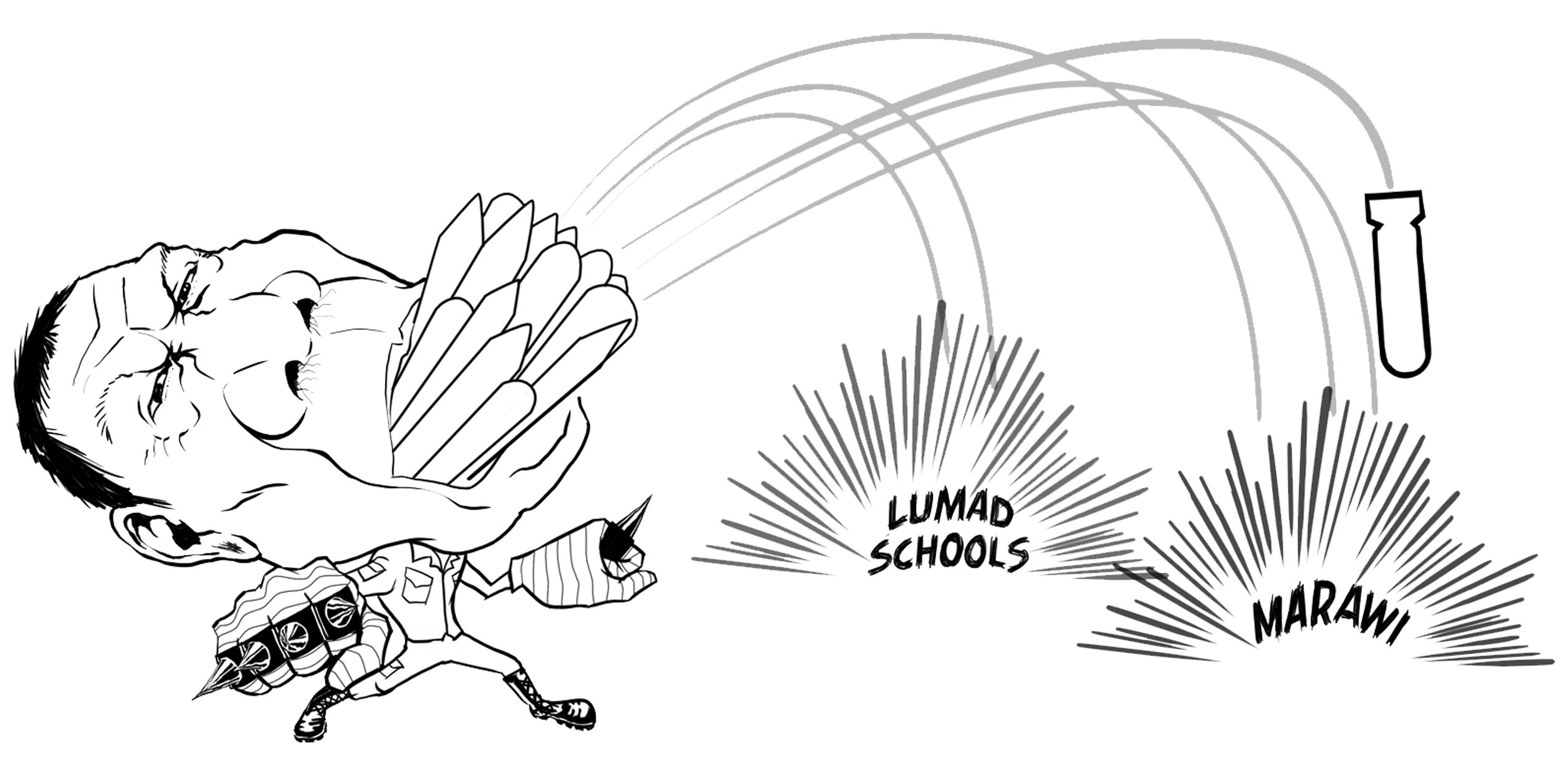

The Marawi City siege — a campaign of suppression against two disgruntled armed groups that used to belong to the Bangsamoro liberation movement — and its consequent displacement of 40,000 Maranaos is only the proverbial tip of the iceberg. Prior to the declaration of martial law on May 23, there were already at least 40,000 documented Moro evacuees affected by the regime’s “anti-terrorism” campaign.

On a nationwide scale, the US-Duterte regime pursues the nearly five-decade counterinsurgency war, now tagged as an “all-out war” through Oplan Kapayapaan, against the national democratic revolutionary movement which has included as targets the various national minorities.

From July 2016 to June 2017, at least 60,000 indigenous peoples have fallen victims of the counterinsurgency war. This is because the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) has tagged large sections of the national minorities as supporters and mass base of the New People’s Army (NPA) and considered them as “legitimate” targets of armed attacks.

Those targeted as “terrorists” in Mindanao are members and families of several armed groups that have emerged from the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) which had negotiated and signed separate peace agreements with the Government of the Republic of the Philippines (GRP) — the MNLF in 1998, the MILF in 2014.

These former members of the MNLF and MILF have rejected the peace process that has failed to address their fundamental demands for reforms urgently needed to realize their right to self-determination. Even the leaderships of the MNLF and MILF feel aggrieved by the failure, mainly on the part of the reactionary government, to implement the signed peace agreements .

A year ago, Duterte spoke with umbrage about the long history of injustice committed against the Bangsamoro by the American imperialist invader-colonizers and the successive neocolonial Philippine governments . He swore to obtain redress for the injustices. But redress, through the implementation of the signed peace agreements however flawed and inadequate these may be, have yet to find fulfillment.

As regards the non-Moro national minorities, the fascist attacks on their communities combined with the schemes to seize their communal lands and natural resources for exploitation by big foreign and domestic corporations threaten to displace them from their ancestral domains and destroy their indigenous cultures.

Rectification of the national minorities’ exploitation and oppression cannot come from the oppressive and exploitative classes. Neither can it be expected from the reactionary state, which these ruling classes have controlled. Government after government has largely been indifferent to their interest and welfare, and in many instances has aided in perpetuating their national oppression and exploitation.

Recognizing this fact, the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP) has committed to undertake the task of rectification in close cooperation with the Bangsamoro, the Cordillera peoples, and other indigenous peoples in the country. Certain provisions in its 12-point program, which takes off from the Communist Party of the Philippines’ (CPP) Program for a People’s Democratic Revolution (PPDR), uphold the right of the national minorities to self-determination and democracy.

Historical injustice and national oppression

By their formidable instinct for survival, the national minorities fought both the Spanish colonialists and the American imperialist plunderers. They resisted the attempts of the colonizing powers to get them integrated into the “larger” society, fearing they would lose their ancestral lands and their distinct identities, cultures and traditions.

Their instinct has proved them right. The colonizers and their native subalterns and, as already mentioned, the succession of neocolonial governments continually tried to dispossess them of their ancestral lands and territories. They were deceitfully enjoined to sacrifice for the “national interest” or in the name of the “majority Filipinos”. Armed terror was used to subdue them. Divide-and-rule tactics was used to pit them against one another and against the majority of the Filipinos. Their traditional institutions were undermined.

Throughout history, the national minorities persisted in preserving their distinct cultures. But, they became victims of cultural discrimination, Christian chauvinism, and Islamophobia that have been deeply inculcated into the minds of the majority Filipinos by the State through the use of mass media and the educational system.

Today, like the rest of the Filipino people, the national minorities are confronted with the problems brought about by US-imperialism, feudalism and bureaucrat capitalism. But in addition to these, national oppression perpetrated by the State, in collaboration with the landlords and comprador bourgeoisie, weighs down on them. The State has become the main violator of the rights of the national minorities to chart their own economic and cultural development and their own systems of governance.

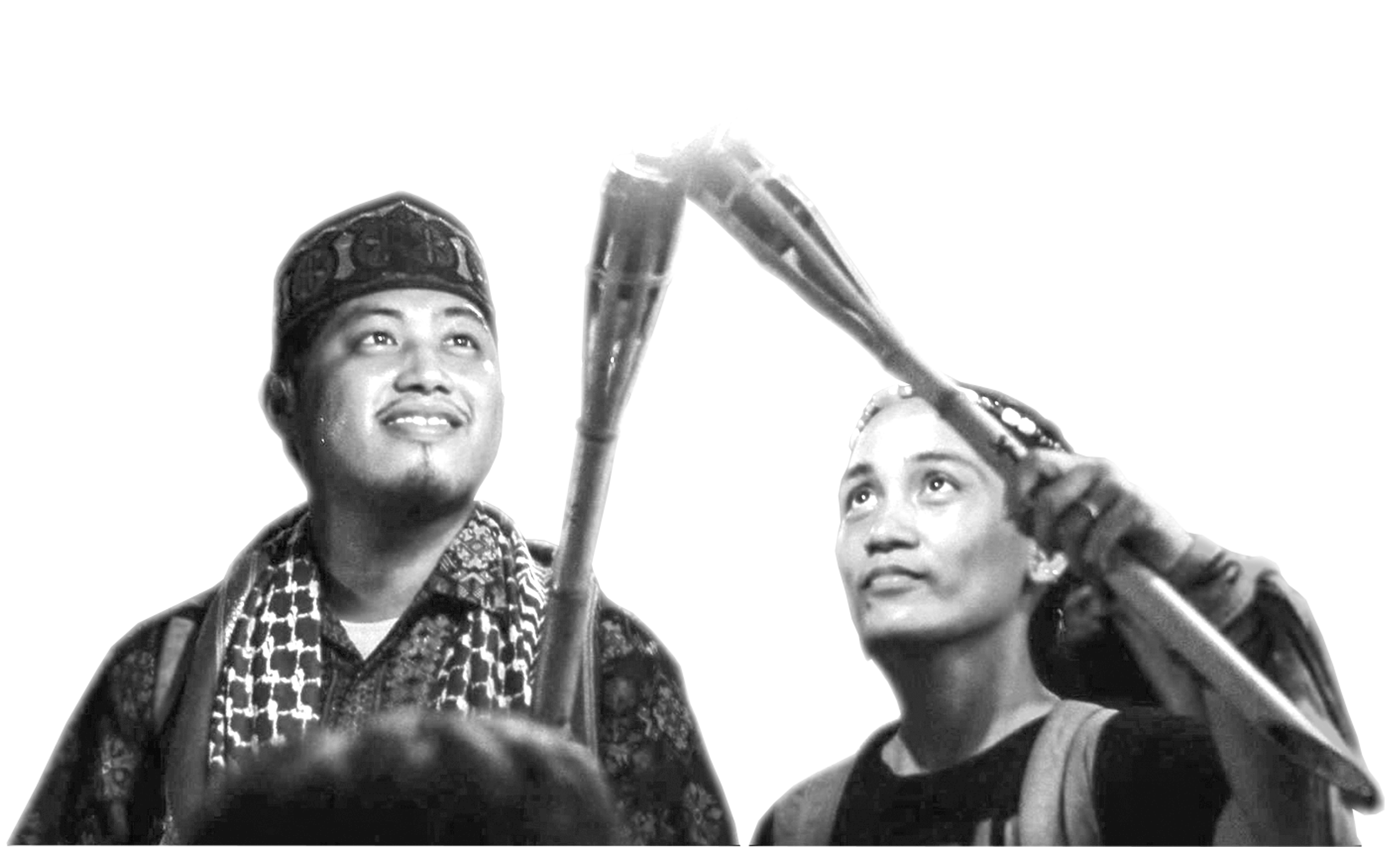

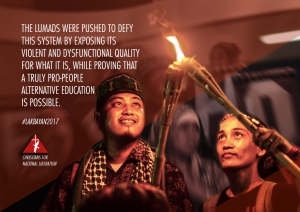

The national minorities are among the most impoverished in the countryside. They are the last to receive social services from the government. Most of them die without seeing a doctor, and most of them die without having a day in school. Their organized efforts, aided by missionaries and other support groups, to build facilities for self-determining communities are targetted for fascist attacks by the State. These include their schools and literacy-numeracy programs, their agricultural cooperatives, and other economic endeavors aimed at lifting them from endemic poverty.

In defense of corporate interests, the State has bastardized the indigenous peoples’ social and political systems, for instance, by transforming the traditional community defense system into paramilitary groups to be used against them. These groups act as the AFP’s “force multipliers” and frontliners in its campaigns of suppression. Military officials are bestowed with the title of “datu” or chieftain to deodorize and legitimize their authoritarian presence in the ancestral lands and territories.

Attempts by the post-Marcos regimes to placate the Bangsamoro and indigenous peoples proved to be futile. The supposed regional autonomous governments granted to the Bangsamoro and the Cordillera peoples were led and mismanaged by the elites and corrupt bureaucrats. The same is true with the various peace and ceasefire agreements between the government and the MNLF and later with the MILF and the Cordillera Peoples Liberation Army (CPLA). All have failed to respond to the basic needs of the national minorities, to protect their rights to their ancestral lands and territories, and uphold their right to self-determination. These have only fueled more frustrations, anger, and armed resistance.

The right to self-determination

The right of the Bangsamoro, the Cordillera peoples, and other indigenous peoples to self-determination, from the NDFP’s viewpoint, means the right to “decide their own destiny; to free themselves from national exploitation, chauvinism and discrimination; to achieve democracy; to rule themselves and to pursue social progress in an all-round way and in accordance with their specific conditions.” Under conditions of national oppression, this right extends to the right to secede.

All efforts must be exerted, therefore, to encourage the Bangsamoro to opt for the more valid and viable option of a genuine autonomous political rule within the framework of “equality of all peoples and nationalities” under the prospective People’s Democratic Government. Genuine autonomy is also guaranteed to the Cordillera peoples.

Self-governance within the People’s Democratic Government is key to genuine autonomy. Through this government structure, the full participation of the national minorities to decide on all matters affecting their lives is ensured. The autonomous regions shall be responsible for the concerns on the right to ancestral land, respect for tradition and culture, employment and economic opportunities, and how the economic development in the ancestral lands and territories can benefit the national minorities and hasten their social progress.

For the national minorities outside of the autonomous areas, they shall be accorded with meaningful and proportional representation in the organs of political power at various levels and in the National People’s Congress.

While encouraging active interaction among the diverse cultures in the country, the Bangsamoro, Cordillera, and other indigenous peoples’ social, religious, cultural, legal and customary laws shall be respected. Specifically for the Moro people, the “historical, social and religious ties with their Islamic brethren abroad shall likewise be respected.”

The NDFP believes that the national minorities, given their particular history and current situation, should get all the necessary support to enable them to “advance and progress with the rest of the nation.” Thus, its program explicitly provides that the central government of the new republic shall extend all help to the autonomous areas and peoples to develop according to their “decisions and specific conditions.”

Through the autonomous regions and the representation of the national minorities in all levels of governance, “equal political, economic and social rights as well as respect for their way of life shall be guaranteed.”

Advancing the revolution

Among the NDFP’s 18 allied organizations are the revolutionary formations of national minorities such as the Moro Resistance and Liberation Organization (MRLO), the Cordillera People’s Democratic Front (CPDF) and the Revolutionary Organization of Lumad (ROL). Other national minorities are part of the CPP-NPA structures in the guerrilla zones in various parts the country.

These revolutionary organizations are waging armed resistance which is integrated in the national democratic struggle led by the Communist Party of the Philippines, New People’s Army and the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (CPP-NPA-NDFP).

Outside of these revolutionary organizations, particularly among the Bangsamoro, the armed resistance is growing. Absent viable channels for redressing their historical grievances, extremism such as what the ISIS advances becomes an attractive alternative. But an end to national oppression cannot be achieved in that direction, neither can it be ended within the existing social order.

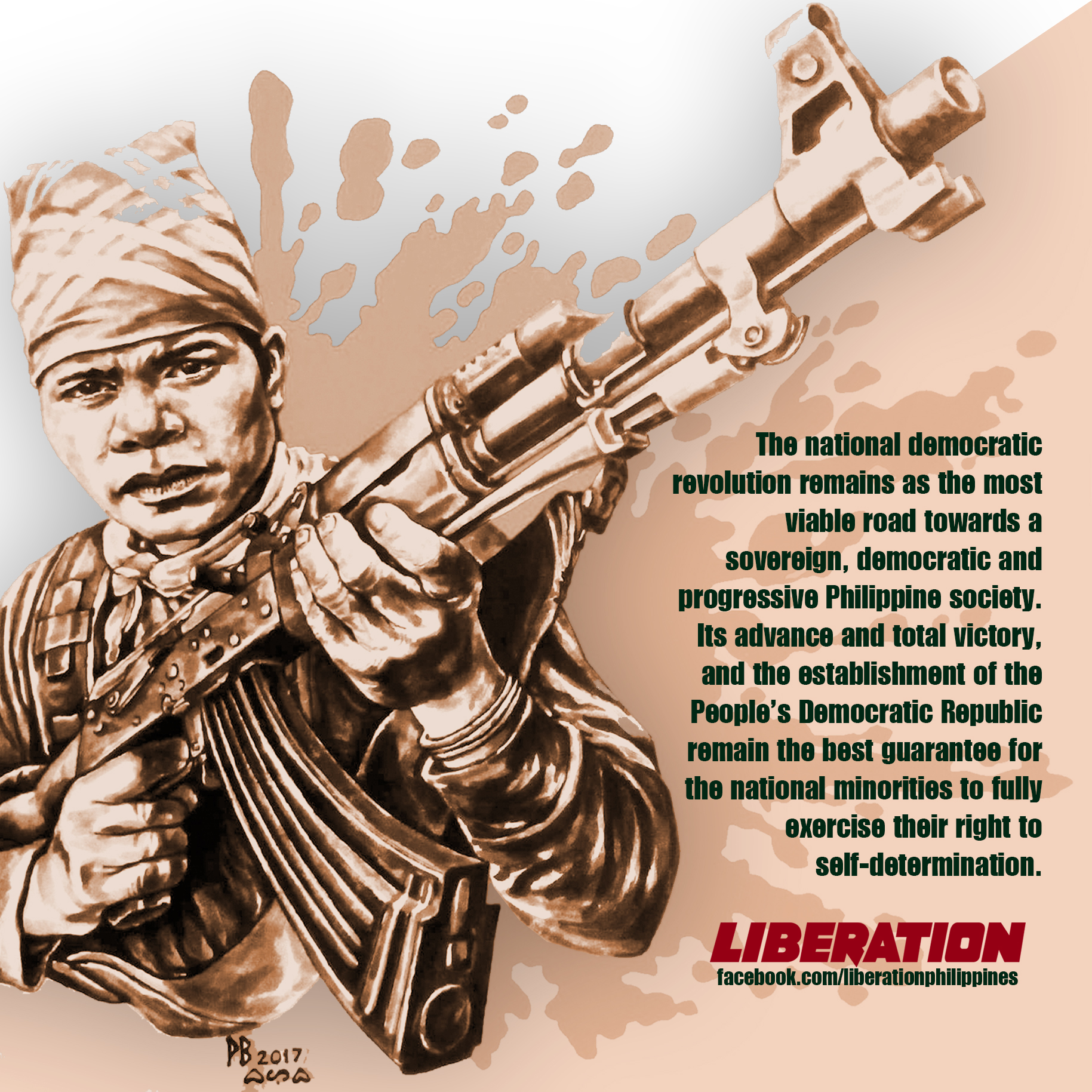

To this day, the national democratic revolution remains as the most viable road towards a sovereign, democratic and progressive Philippine society. Within it the national minorities constitute a potent force in fighting the common enemy. Its advance and total victory, and the establishment of the People’s Democratic Republic remain the best guarantee for the national minorities to fully exercise their right to self-determination.

Back-channel talks

Back-channel talks