by Angel Balen

As he began his six-year term in July 2016, President Rodrigo R. Duterte set off a momentum for change by taking bold, dramatic moves and making definitive pronouncements in pursuance of his campaign cry, “Change is coming!”

However, towards the latter part of his first year in power the momentum for change has faltered. He has tended more and more to backslide towards the Right. Dragged and rendered as casualty in that flow and ebb were the peace talks of the Government of the Republic of the Philippines-National Democratic Front of the Philippines (GRP-NDFP), which Duterte had vowed to resume, and to complete and begin implementing the substantive agreements (on social, economic and political reforms) within his term.

The formal negotiations resumed on August 22 in an atmosphere of amity and euphoria: the new president had caused the release of 21 NDFP consultants and staff, enabling them to participate in the talks. As regards the other 400 political prisoners, he had offered (in May before he took office) to issue an amnesty proclamation to expedite their release.

The two parties reaffirmed the 12 previously signed agreements (from 1992 to 2004) and “resolved to conduct formal talks and consultations in accordance with said agreements” (Joint Statement, August 26, 2016). They reconstituted the list of NDFP consultants given safety and immunity guarantees under the JASIG (Joint Agreement on Safety and Immunity Guarantees) and completed the requisite guidelines to implement the CARHRIHL (Comprehensive Agreement on Respect for Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law).

Furthermore, they have agreed to accelerate the pace of the negotiations, setting up the necessary mechanisms and procedures, and made significant gains in three successive rounds of formal negotiations until the end of January 2017. Then something happened that rudely interrupted the good things going on so well, as acknowledged by both negotiating panels.

“Moving the Peace Talks Forward,” the lead article of Liberation, January-March issue, pointed out the main factor that has since impeded the relatively smooth flow of the peace negotiations. “War hawks in the administration, led by pro-US defense and military officials,” the article said, “soon began undermining the strides made in three rounds of formal peace talks in the first six months of the new government.”

The war hawks avidly exploited to their advantage an initiative by President Duterte (which they had probably suggested) that has turned into a problematic and troublesome element in the peace talks: his declaration on August 21 of an indefinite unilateral ceasefire.

In May 2016, when as president-elect he met with then NDFP emissary Fidel Agcaoili and committed to resume the long-suspended peace talks, Duterte did not at all speak of a ceasefire. Neither was a ceasefire declaration discussed during the June preliminary bilateral talks between his emissaries and the NDFP negotiating panel held in Oslo, Norway. But when he delivered his first state-of-the-nation address in July, he announced a unilateral ceasefire, which he hastily withdrew because the NDFP did not immediately reciprocate with a similar ceasefire declaration. It was explained to him later that the NDFP had waited for details on how the ceasefire would be implemented before issuing its reciprocal unilateral ceasefire declaration.

A day before the formal resumption of the peace talks, Duterte again declared an indefinite unilateral ceasefire. This time the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and the NDFP responded by declaring their reciprocal indefinite unilateral ceasefire.

Devious plan

Absent mutually-agreed guidelines for implementing the reciprocal unilateral ceasefires, the war hawks moved fast to carry out their devious plan: aggressively they pushed Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP )counterinsurgency operations, misrepresented as assistance to government “peace and development” programs, in hinterland and rural communities under the control or influence of the CPP and the New People’s Army (NPA). Over five months, AFP intruded into and occupied 500 barangays nationwide, spurring complaints from the affected communities that the state security forces subjected them to threats, harassments, and other forms of abuses and human rights violations. The violations have been duly documented by the human rights monitoring organization, Karapatan (whose Secretary General is an independent observer in the Joint Monitoring Committee [JMC] under the CARHRIHL), and submitted to the NDFP panel.

Through those five months, the ceasefire held as the NPA consistently evaded engaging the intruding state forces in combat, thus evincing sincere adherence to its own unilateral ceasefire declaration. However, the CPP raised to the NDFP panel its complaints against the AFP’s persistent deceitful violations of the ceasefire. On two occasions — Nov. 4, 2016 and Jan. 4, 2017 — the NDFP panel handed over the documented complaints to the GRP panel.

Having observed no change in the AFP’s actions, the CPP served notice to the NDFP panel that the situation on the ground was becoming untenable, and that soon it would withdraw its ceasefire declaration. During the third round of formal talks (held in Rome in late January), the NDFP panel relayed that notice to its government counterpart, warning that the AFP violations were already endangering the peace talks. On February 1, 2017, the CPP announced its ceasefire withdrawal.

Although he was apprised by the NDFP panel of the reason for the withdrawal, President Duterte angrily reacted to the maliciously distorted information fed to him by the war hawks about the NPA allegedly violating its own ceasefire. Peremptorily he cancelled the peace talks and in his characteristic blustering called the NPA “terrorists”. Picking up from there, his defense secretary declared an “all-out war” against the NPA, egregiously tagging the NPA as “terrorists no different from the Abu Sayyaf”.

Back-channel talks

Back-channel talks

Within three weeks Duterte walked back on his cancellation of the peace talks, taking recourse in back-channel talks towards continuing the formal negotiations. Perplexingly, he didn’t rescind the Defense Department’s all-out war declaration. He even egged on the AFP and Philippine National Police (PNP) to use all their assets and “flatten the hills” (the presumed redoubts of the NPA) through aerial bombings and artillery bombardments.

That was not all he failed or opted not to do before the fourth round of negotiations began in April. During the March 11 back-channel talks, the two parties agreed that upon resuming the cancelled negotiations each side would issue simultaneous and reciprocal unilateral ceasefire declarations. But according to his defense secretary, Duterte didn’t order the issuance of the GRP declaration. Hence the NPA had no choice but to engage in self-defense and counter-offensives.

Thus the all-out war has continued to this day. And aerial bombings plus ground artillery barrages have become a feature of the state counterinsurgency forces’ mode of combat. This has caused recurrent large-scale evacuations of rural communities targeted by the bombings in Mindanao and other parts of the country. (Daily air bombings have also punctuated the AFP operations against the Maute group in Marawi City for more than three months now.)

We know who are the war hawks and main peace saboteurs: Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana, National Security Adviser Hermogenes Esperon Jr., AFP Chief of Staff Gen. Eduardo Ano, and other government officials in the Duterte Cabinet so-called security cluster. They have sustained black propaganda, aimed at discrediting the Red Fighters, casting doubt on the sincerity of the revolutionary forces in the peace negotiations, and impugning the credentials of the NDFP panel.

Fourth round of talks

The cabinet security cluster’s intervention delayed for two days the opening ceremonies of the fourth round of negotiations, held in The Netherlands. There being no ceasefire in place, they pressed the GRP panel to insist on placing in the agenda the negotiation and signing of a prolonged indefinite bilateral or joint ceasefire agreement ahead of the scheduled negotiations on a Comprehensive Agreement on Social and Economic Reforms (CASER). The NDFP panel rejected the proposal, saying it violates the previously signed agreements both panels had reaffirmed and agreed to comply with, foremost the four-point agenda set by The Hague Joint Declaration (1992), and the Joint Agreement on the Sequence, Formation and Operationalization of the Reciprocal Working Committees (1995).

Nonetheless, the fourth round of negotiations concluded with positive results.

The two panels skirted the threatening impasse by crafting and signing an Agreement on an Interim Joint Ceasefire, which provides that the guidelines and ground rules for implementation will be worked on by the panels’ respective ceasefire committees “in-between formal talks”. No ceasefire can take effect until after the guidelines and implementing rules have been finalized, signed by the panels and approved by the principals of both parties.

Meantime, the reciprocal working committees on the CASER firmed up their agreement that distribution of land to landless farmers and farm workers for free is “the basic principle of agrarian reform”. (Agreement in principle on this matter was arrived at in the third round of talks.)

For the records, presidential peace adviser Jesus G. Dureza hailed the fourth round as “the farthest point we have already achieved in our negotiations with the CPP-NPA-NDF”. And he stated that in his formal statement at the opening ceremonies.

But the cabinet security cluster didn’t find the agreement on an interim ceasefire suitable to them. At the scheduled fifth round of negotiations in May, they pressed on with their original proposal that the NDFP definitively had rejected. Not only that. They demanded that the CPP recall its order to the NPA for intensified tactical offensives against state security forces to manifest its opposition to Duterte’s May 23 declaration of martial law and suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus in the whole of Mindanao — which targeted the “dismantling” of the NPA.

GRP pulls out

Buckling to such pressure, the GRP panel announced it would not participate in the fifth round. That was a bad move—made worse by Duterte’s warning the NDFP consultants then in The Netherlands not to return to Manila as he would have them incarcerated. For a number of days both the GRP and NDFP delegations were stuck at the hotel venue, holding ad-hoc unilateral meetings, and taking walks in between free meals courtesy of the Royal Norwegian Government. Third party facilitator Ambassador Elisabeth Slattum tried, in vain, various means to get the two panels, or the reciprocal working committees, to sit down together even informally and discuss matters of mutual concern.

Of course, the peace saboteurs succeeded in obstructing the progress of the negotiations on the CASER because President Duterte permitted their scheming. He wanted to assuage the war hawks bent on wangling a prolonged bilateral ceasefire as a means to stanch the sustained growth in strength of the revolutionary forces, dreaming of pushing the latter ultimately into capitulation and pacification, as has happened in the cases of many peace agreements in other parts of the world.

The NDFP has made it clear it’s fully aware of the war hawks’ capitulation-pacification trap and does not wish to fall into it. Besides, putting in place a prolonged and indefinite ceasefire agreement before there are substantive agreements on social, economic, political and constitutional reforms, it emphasizes, will betray the trust of the oppressed and exploited masses, the intended prime beneficiaries of such reforms.

Similarly, Duterte wanted to placate the neoliberal clique composing his economic managers and the pro-imperialists in various government offices. They make no bones about their opposition to the social and economic reforms that are moving towards adoption in the peace negotiations—particularly the basic concepts and ramifications of a genuine agrarian reform program and rural development (ARRD) and of national industrialization and economic development (NIED).

Duterte made the hollow excuse that he has to consult many advisers, particularly the military — which he has been pampering with financial and other incentives. He claimed that he has no control on everything within his vast sphere of authority. Thus he has become mum on his publicly-repeated commitment to accelerate and complete the peace negotiations on substantive reforms. Worse, he has reneged on his offer of amnesty for the 400 political prisoners identified in a list submitted by the NDFP panel.

Ironically, the President hems and haws just as the talks are beginning to produce results that open up opportunities for his “government of change” and the NDFP to work together in improving the dire living conditions of the people, particularly of the majority poor, which he has vowed to ameliorate.

In July, President Duterte had cancelled the back-channel talks between the two panel heads and their working teams on what should be in the agenda of the fifth round of formal negotiations, tentatively set in the latter part of August.

No mood for talks

In a long adlib portion of his second state-of-the-nation address, Duterte said he was no longer in the mood to talk peace with the Left. He let out his recrimination over the NPA’s continued attacks on government forces and installations after he had declared martial law in Mindanao. Exaggerating an incident in Arakan, North Cotabato on July 20, he publicly claims the NPA planned to ambush him in one of his land travels through the region. “How can we talk when you’re ambushing me!” he blustered.

Of course, there was no such plan to ambush the President. What actually happened was that the NPA had set up a checkpoint in Arakan to deliver a message: that under martial law, the NPA can set a checkpoint in an area it chooses along the highway, as it has been doing for years.

Coincidentally, two unmarked vehicles that the sentries had stopped to check on turned out to belong to the Presidential Security Group. When the driver of the first car sensed the odd situation, he sped through the checkpoint. In quick reaction, the Red fighters shot its rear wheels stopping the vehicle. The second car also sped past the checkpoint. Although it managed to get away, it met with a volley of gunfire that wounded four of the men on board. After a while, the NPA unit left the area without harming the men who locked themselves inside the stalled PSG vehicle.

Will the peace talks continue?

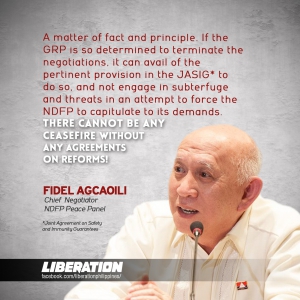

Thus far the GRP has not made a formal written notification to the NDFP terminating the JASIG, which in effect would also terminate the peace talks. The protocol calls for the NDFP to acknowledge the notice of termination, which would take effect 30 days after the acknowledgment.

Meantime, all the NDFP consultants “stranded” in The Netherlands to evade arrest have safely returned to the Philippines. However, the gung-ho solicitor general (the government’s chief lawyer) has filed a court petition calling for the cancellation of their bail to enable the police to re-arrest them. Thus far no further legal action has been announced.

Just before the solgen’s precipitate move, another small window was opened. Ten of 19 convicted political prisoners were freed

via conditional presidential pardon, including one of three NDFP consultants. The 19 had been convicted of trumped-up common crime charges and were already recommended for conditional pardon. Peace advocates are pushing for the release of more political prisoners to improve the chances of continuing the peace talks.

During the waiting period, bilateral discussions on the CASER have continued in Manila. The bilateral teams formed to help reconcile contentious provisions in the GRP and the NDFP drafts of the CASER recently held a three-day working meeting. The meeting has achieved consensus on many aspects of agrarian reform and rural development (ARRD), including the scope and coverage, disposition of land, and modes of compensation to landowners. They are expected to submit recommendations to their respective reciprocal working committees, which can help accelerate the formal negotiations on the CASER.

As matters stand, it’s obvious that the interruptions of the peace negotiations caused by the ceasefire imbroglio since February have put in jeopardy the mutually-targeted completion of the CASER negotiations before the end of 2017. At best, in the next formal negotiation rounds the panels can target the completion of a partial agreement on agrarian reform and rural development.

But that can happen only if the GRP relents on pushing ahead negotiations on a prolonged bilateral or joint ceasefire.