CRACKS ON THE WALL 2.0

by Vida Gracias and Pat Gambao

The dream was high on words.

On April 18, 2017 President Rodrigo Duterte’s economic team went on a hype to sell to the public “DuterteNomics” in a forum at Conrad Hotel in Pasay City.

All the President’s men where in attendance: Executive Secretary Salvador Medialdea, Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez, Executive Director Ernesto Pernia of NEDA (National Economic and Development Agency), Budget Secretary Benjamin Diokno, Secretary Mark Villar of the Department of Public Works and Highways, Secretary Arthur Tugade of the Department of Transportation, Secretary Martin Andanar of the PCCO (Presidential Communications Operations Office), President/CEO Vince Dizon of the Bases Conversion and Development Authority, and Board Chair John Gaisano of the Davao City Chamber of Commerce.

They took turns in explaining the President’s economic and development blueprint for the Philippines.

According to the website duterte.today the coined word includes the regime’s “main governance and fiscal policies, comprehensive big-ticket infrastructure programs and upgraded social services targeted to accelerate growth, and by 2022, transform the Philippines into a high-middle income economy.”

A year after that forum and way into its third year “Dutertenomics” remains, at best, a fantasy and, at worst, a catastrophe.

Difficult times

Difficult timesIf government statistics were to be believed Dutertenomics is on its way to making the Philippines the fastest growing economy in Southeast Asia. But the picture on the ground says differently.

Inflation (the rise in the prices of goods and services) is running high—5.2% in June, 5.7% in July, 6.4% in August, 6.8% in September. Damaging as it is, the onslaught of typhoons such as ‘Ompong” and ‘Rosita’ is shooting up inflation. Rising inflation almost always hits the poor the hardest. But even corporate firms complain it cuts into their profit.

On the current rice crisis, the regime has resorted to removing the import quota, importing 750,000 metric tons for 2018. Despite this, rice prices increased 24 times from January to June 2018, according to the Philippine Statistics Authority. At the height of the rice crisis in August, the price of rice in Zamboanga went up to PhP 70 per kilo.

To further arrest price hikes, the regime imposed a suggested retail price (SRP) in four varieties of rice—namely, imported rice, regular local rice, well-milled rice, and whole-grain rice—but with penalties and fines for retailers. Duterte has also certified as urgent the Rice Tariffication Bill, which will remove all quantitative restrictions (QR) on rice importation. Once imports swarm the market the Filipino farmers cannot be competitive.

More severe is the job crisis, according to research group IBON. There are less jobs available in 2018 compared to the start of the Duterte administration. Jobs fell by 295,000 from 40.95 million in July 2016 to 40.67 million in July 2018. IBON conservatively estimates at least 11.3 million unemployed (4.3 million) and underemployed (7.0 million) Filipinos as of July 2018, which is one in four (25%) of the labor force.

A paltry wage hike of PhP 25 plus PhP 10 cost of living allowance was given to workers in the national capital region recently (it’s even lower outside the region). But the PhP 537 minimum wage in NCR alone is way below (or 46.3% short) of the PhP 1,000 family living wage (FLW), or the amount that a family of five needs for decent living as of October 2018.

The brainchild to increase revenues through taxation has been a disaster. Intended to fund the regime’s ambitious “Build, Build, Build” (BBB) program through TRAIN 1 (Tax Reform for Acceleration and Inclusion), the law, which took effect in January 2018, fueled inflation even more.

The excise tax on petroleum, tobacco and sweetened beverages created a domino effect on prices. Government monthly subsidy of Php 200 per family was meant to cushion the effects of TRAIN on the poor specially for 100 million families under the PhP 24-billion unconditional cash transfer program. But this was not fully implemented. Also, whatever tax exemption that is given to minimum wage earners is cancelled out by inflation.

TRAIN 2 (renamed or rebranded as Tax Reform for Attracting Better and High-quality Opportunities or TRABAHO) which takes effect in January 2019 is meant to reduce corporate tax of 30% to 20% and increase incentives for business. Opposing it, the Bayan Muna Partylist said that the loss in government revenues will only benefit big corporations while more taxes will be levelled on the poor.

BBB will drive this country further into debts. Japan is putting in PhP 20.6 billlion, Asian Development Bank (ADB) will extend $7.1 billion in loan assistance, and the China-led Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank (AIIB) is expected to fund the construction of health facilities, school buildings and roads.

Already, as of December 2017, the country’s total outstanding debt stood at PhP 6.65 trillion. In the four months from January to April 2018, government borrowing has already reached PhP 244.6 billion. As of end-2018, the outstanding debt has reached beyond PhP 7 trillion.

Meanwhile, the peso has depreciated against the US dollar, its weakest in 11 years. Currently standing at PhP 54 to a dollar, it has also become the third weakest currency in the world. This means imports are getting more expensive while exports earn less, leading to greater trade deficits. Export earnings further declined with less shipment of coconut products, fruits and vegetables.

But, interestingly enough, the Bangko Sentral ng Philipinas (BSP) said that the massive trade gap is due in part to the import requirements of the Php 9 trillion (or $180 billion) infrastructure buildup plan of the Duterte government.

All told, uncertainties surround “Dutertenomics” with Duterte himself fanning it. Many foreign partners, particularly the European Union (EU) and Canada, are put off by Duterte’s crass behavior and attacks. The Asian Review noted that hardly any major European business delegation has visited Manila, due to concerns over rule of law as well as bilateral diplomatic spats, such as the barring of a high-level EU party official, Giacomo Filibeck, a vocal critic of Duterte’s drug war, from entering the Philippines. The EU is the Philippines largest export market, worth $10 billion in 2017.

Whether it be “Dutertenomics”, Benigno (Noynoy) Aquino’s “inclusive growth”, or Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo’s “Strong Republic”, not one regime can claim that it is resolving the nation’s chronic crisis and leading the country to growth.

The situation has just gone from bad to worse. Current and past regimes simply took the road of neoliberalism (liberalization, privatization, deregulation) on the economy as dictated by the imperialist-controlled International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the World Trade Organization. The result is disastrous as it aggravates the fundamental problem—of a country remaining semicolonial and semifeudal.

That is why “Dutertenomics” cannot bust poverty, unemployment, inflation, low wages, lack of social services that have bedevilled millions of Filipinos today and in the past. Even more so is the illusion that “Dutertenomics” can raise the status of the majority of Filipinos from being poor farmers and workers to middle class.

Nature of economy

Nature of economyThe Philippine economy is basically agrarian. It lacks industries that can produce basic metals, basic chemicals and capital goods. Even light industries depend mainly on imported capital goods. Manufacturing involves slight processing or mere assembly of imported components.

Because of its backward, agrarian nature, the country has always suffered from trade gaps or deficits in the balance of trade. Its exports have consisted mainly of low-value agricultural products (sugar, copra, coconut oil), logs, raw extractive minerals, manufactured consumer goods and reassembled components compared to its imports.

To fill in the gap, the government always resorts to borrowing, which is why the country is perpetually in debt, making it more vulnerable to impositions by international creditors.

Over the years, the Philippines has not gone beyond being a supplier of raw materials to the capitalist world, a dumping ground for imported goods, and a source of cheap labor. This is so because the economy remains under the tight grip of foreign monopolists and big local landlords and compradors. And there is no way “Dutertenomics” is ever changing this landscape.

Just look at the 10 Filipino billionaires (Henry Sy, Manuel Villar, John Gokongwei, Enrique Razon, Jaime Zobel de Ayala, Ramon Ang, Tony Tan Caktiong, Lucio Tan, George Sy and Andrew Tan) who made it to the Forbes list. Their investments are tied up into an export-oriented and import-dependent economy. This has uplifted the fortunes of the country’s richest. Under the Duterte regime, at least 19 tycoons were reported to have their networth shift 20% or more over the past year.

The country is rich in land, human and natural resources (mineral, waters, marine, flora and fauna) and could very well develop into a prosperous, self-reliant economy. But “Dutertenomics” will only further worsen the country’s dependence on US and other imperialist powers, notably through TRAIN and cha-cha (charter change).

Key to development

Key to developmentThe Filipino people have cried for true agrarian reform and national industrialization as the key to development. But this has been totally ignored and mocked by “Dutertenomics”, which does not only retain and expand private monopolies but would even allow 100 percent foreign ownership of agricultural land.

As “Dutertenomics” creates more havoc to the economy, the more people look up to the National Democratic Front of the Philippines in laying down the fundamentals for a sound economy. The NDFP’s proposed Comprehensive Agreement on Social and Economic Reforms (CASER) which was presented and discussed in the scuttled NDFP-GRP peace talks is an economic blueprint that has come out of the insights and practices of several decades of revolutionary struggle.

In the countryside it is common knowledge that the the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and its armed wing, the New People’s Army (NPA), are carrying out agrarian reform as the main content of the democratic revolution. This consists of a minimum and a maximum program. Minimum includes rent reduction, elimination of usury, setting of fair farm-gate prices and promotion of agricultural production and sideline occupation through independent households and rudimentary cooperation. Maximum involves the confiscation of land from the landlords and land grabbers and free land distribution and agricultural cooperation in stages.

Freeing the economic forces in the countryside will serve as basis for the advent and growth of more industries that, under the supervision of the people’s democratic state, would lead to the fulfillment of the people’s basic needs and bring this country to peace and prosperity.

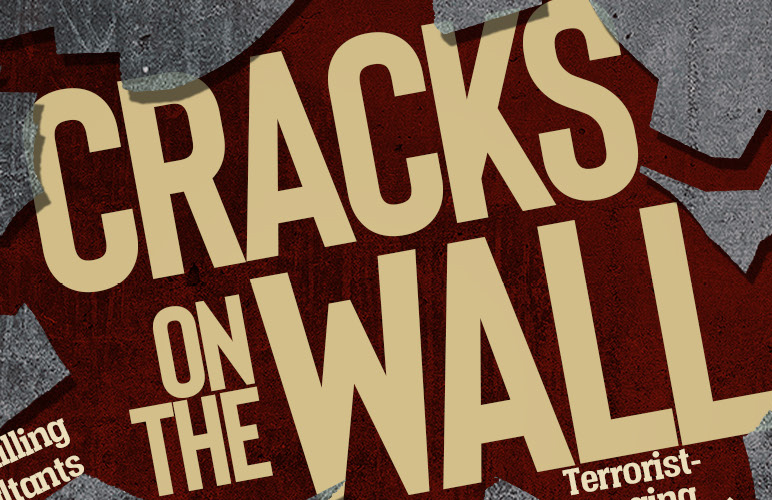

Below is a sampler list indicative of what (or how much) the US-Duterte regime has so far achieved as an

by Erika Hernandez Neophyte Senator Ronaldo “Bato” dela Rosa, the controversial Philippine National Police chief of the Duterte government, recently

Do you see the signs? Now, do the test 🙂 CHECK YOUR SCORE #DuterTerorista #FightTyranny #MakibakaWagMatakot —– VISIT and FOLLOW

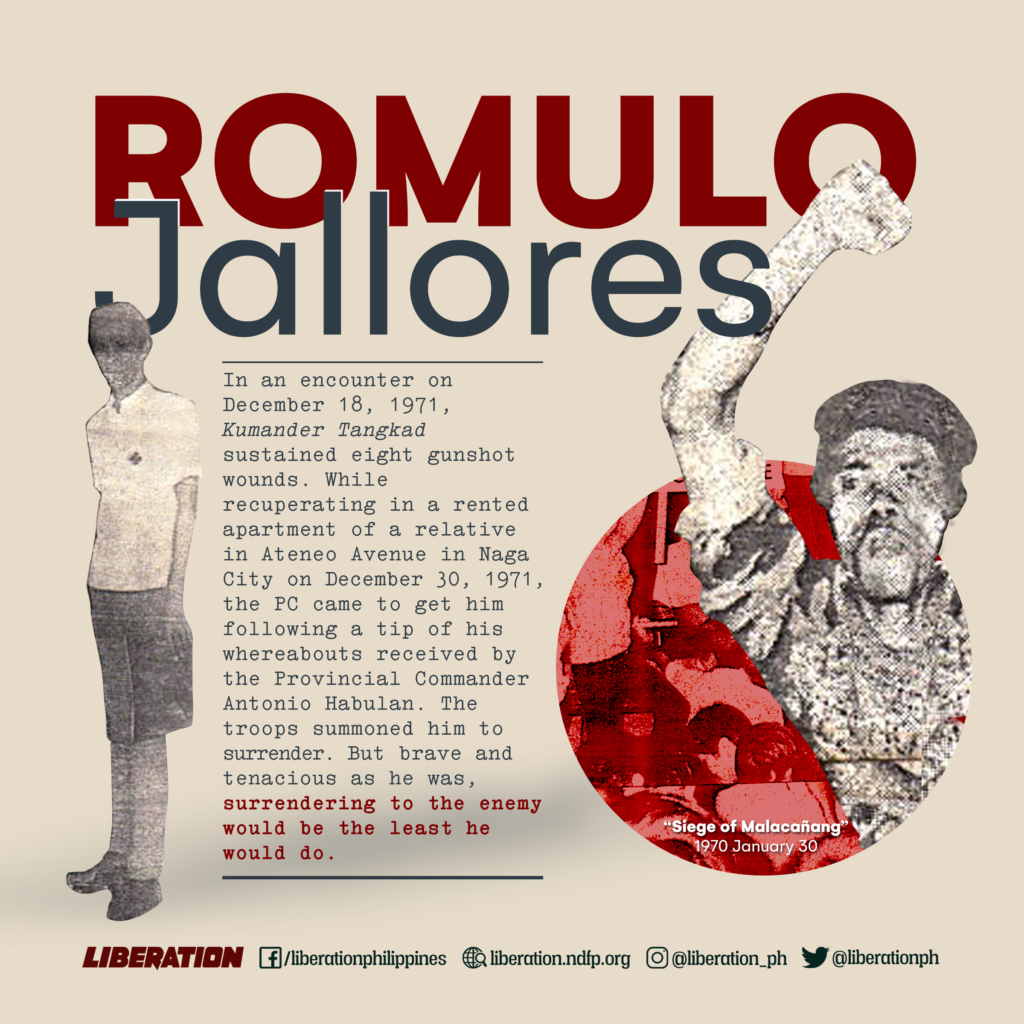

With the upsurge of youth activism in the early 70’s, Romulo Jallores, a third-year high school drop-out who did odd jobs for a living in the periphery of the university belt, was drawn to the youth organization Samahang Demokratiko ng Kabataan (SDK). He attended teach-ins and discussions of the group in reading rooms of the University of the East. He marched with them in demonstrations and protest rallies, his tall built towering over the throng.

Courageous and aggressive, Romulo joined a band of youth in commandeering a truck to ram the gates of Malacañang. That demonstration of January 30, 1970 signalled the start of the First Quarter Storm (FQS). The Nation carried an article on the event entitled “Siege of Malacanang.” In the photo, among the youth on top of the truck, was Romulo wearing a beret like Che Guevara. Ernesto Che Guevara was the Argentinian expeditionary revolutionary whose name created waves not only in Latin America but also across the globe after the victory of the Cuban revolution led Fidel Castro with his help. From then on, Romulo came to be known in the activists’ circle as Che.

Courageous and aggressive, Romulo joined a band of youth in commandeering a truck to ram the gates of Malacañang. That demonstration of January 30, 1970 signalled the start of the First Quarter Storm (FQS). The Nation carried an article on the event entitled “Siege of Malacanang.” In the photo, among the youth on top of the truck, was Romulo wearing a beret like Che Guevara. Ernesto Che Guevara was the Argentinian expeditionary revolutionary whose name created waves not only in Latin America but also across the globe after the victory of the Cuban revolution led Fidel Castro with his help. From then on, Romulo came to be known in the activists’ circle as Che.

Further studies and discussions during his stint in the SDK headquarters in Taytay, Rizal deepened his understanding of the fundamental problems of the Philippine society—of imperialism, feudalism and bureaucrat capitalism. Their relation to stark realities dawned on him: the impecunious situation of their family, a brood of 10 raised solely by their mother; the discrimination he experienced in school because he was not moneyed like his other classmates; the wretched plight of the landless farmers and parahagot in the abaca fields in Tigaon, a town in Camarines Sur.

Concern and compassion for the poor and the oppressed were inherent with Romulo. From boyhood, he had always sided with the underdog—the bullied playmate or the losing one in a game. Selfless, the welfare of others was prime to him. Thus, it was never difficult for him to abide by the call to serve the people.

The high idealism and aspiration of the youth stir them to pursue the path to change, meaningful change that will uplift people’s lives, especially those of the disadvantaged and marginalized. Heeding the words of Mao Zedong, the youth set out to integrate with the masses of peasants and workers—learning from them, consolidating their ideas and experiences, arousing and organizing them, helping them achieve their emancipation.

Romulo, with his elder brother Ruben and student-comrades in the movement, went back to his hometown in Tigaon, Camarines Sur. Initially, they joined in organizing a people’s movement—the Bagong Katipunan which had been short-lived. Later, they proceeded to the rural areas to immerse with the farmers and abaca workers. They helped them plant their food as they enlightened them on issues and as they organized them.

When the writ of habeas corpus was suspended in August 1971, Romulo and Ruben visited their mother to bade her farewell. That was the last time she talked and saw them.

At age 24, the country kid, who had ventured to Manila to earn for a living from odd jobs in garage and machine shop, who had become an activist thirsting for knowledge and hungering for change, had turned into a red fighter, gaining the monicker Kumander Tangkad for his over six-foot height. His brother Ruben took the name Kumander Benjie. Kumander Tangkad believed, as he had learned in the past, that only an armed revolution can liberate the people from the fetters of the semi-feudal structure that US imperialism with its local cohorts of landlord/comprador and bureaucrat capitalist foster. Resting on the creativity and strength of the masses, the people’s war erupted in the hinterlands of Tigaon.

The people rejoiced and fully supported the New People’s Army, their protector from the abusive Philippine Constabulary (PC) and bad elements who stole their carabaos. Making a dent on the control of the fascist troops in the area, the NPA was pursued like mad by the PC.

In an encounter on December 18, 1971, Kumander Tangkad sustained eight gunshot wounds. While recuperating in a rented apartment of a relative in Ateneo Avenue in Naga City on December 30, 1971, the PC came to get him following a tip of his whereabouts received by the Provincial Commander Antonio Habulan. The troops summoned him to surrender. But brave and tenacious as he was, surrendering to the enemy would be the least he would do. Mao’s quotes were ingrained in his mind, “Wherever there is struggle, there is sacrifice, and death is a common occurrence.” “Dying for the interests of the people is a worthy death.”

Using his wounds as pretext, Jallores urged them to come and get him. But as soon as the troops entered the room, they were met with fire from a .45 caliber felling PC Lt. Segundino Agahan dead. Retaliating, the PC riddled Jallores with a volley of shots. Twenty-two bullets on his body snuffed out the life of Kumander Tangkad.

But the legend of Kumander Tangkad lived on and thousands took up the rifle he dropped. The flames of the revolution kindled in Tigaon raged into a conflagration that engulfed and spread throughout the region. In due time, organs of political power were also set up in guerrilla zones.

Here is a gathering of some unforgettable names. They are among our cherished crop of revolutionaries. They are our beloved

Adapted from Punla, the revolutionary literary publication of Bicol The good sons and daughters of the country immerse with the

by Angel Balen

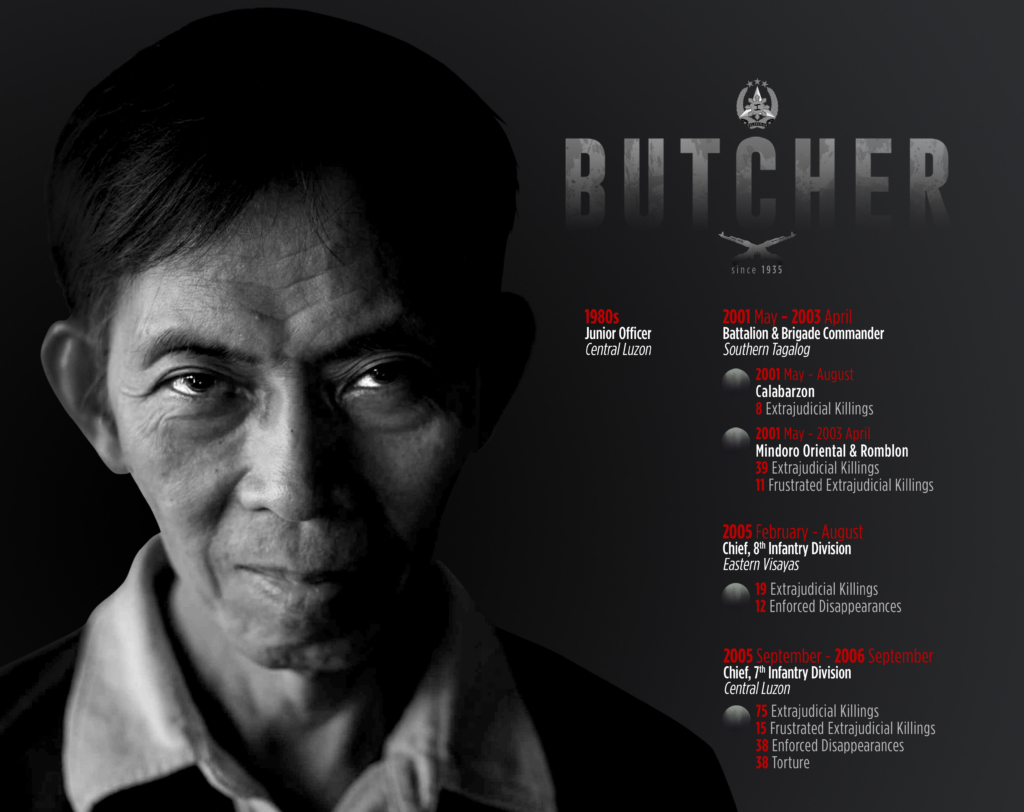

He is gaunt and awkward in physical bearing, lisping in speech, unimpressive for a military officer.

Yet, on his 56th birthday on September 14, 2006, Jovito Palparan Jr. ended 34 years of service in the Philippine Army with the rank of Major General and a hoard of military medals (ranging from bronze to gold).

His shining moment came in July 2006, during President Gloria Arroyo’s state-of-the-nation address before the joint session of Congress: she called on him to stand up in the gallery and gushingly hailed him as her favorite general.

But in the hearts and minds of the informed public, Palparan has been a truly detestable public figure.

When Gloria Arroyo lavishly praised him, the human rights community—national and international—was outraged. Long before that inglorious day, human rights defenders had been roundly condemning him. They excoriated him for his brutal counterinsurgency methods: killing, abducting and torturing mass leaders and activists—noncombatants all—from 2001 to 2006.

A presidential investigating commission on the killings, created in 2006, noted in its report that “there was a rise in the extrajudicial killings of activists and militants between 2001 and 2006, as compared to a similar period prior thereto.” The killings followed a pattern, wherein “victims were generally unarmed, alone, or in small groups and were gunned down by two or more masked or hooded assailants oftentimes riding motorcycles.”

The commission’s head emphasized: “It is undisputed that the killings subject of the investigation of our Commission did not occur during military engagement or firefights. These were assassinations or ambush-type killings, professional hits carrying one out quickly and in the silence escaping with impunity.”

The killings were verified to have risen fast in the three regions of the country to which Palparan had been assigned (Southern Tagalog, Eastern Visayas, and Central Luzon).

The gory operations he started in the Southern Tagalog region, particularly in Mindoro, were topped by the brutal abduction and murder of human rights defender Eden Marcellana and peasant leader Eddie Gumanoy in April 2003. Investigations by the House of Representatives human rights committee resulted in the identification by witnesses of Palparan’s long-trusted executioner, MSgt. Donald Caigas, as the one who led the perpetrators.

It was in Southern Tagalog that Palparan earned the derisive monicker, “The Butcher.” And he seemed to have derived supreme pride for being called that, as the star performer in human rights violations under the Arroyo regime’s two-phased counterinsurgency program, Oplans Bantay Laya I and II.

But inevitably the time of reckoning for Palparan’s crimes had to come. And it came on September 17, 2018—12 years after he retired from military service.

On that date, the Malolos Regional Trial Court Branch 15, presided over by Judge Alexander Tamayo, convicted Palparan for just one of the numerous crimes attributed to him: kidnapping with serious illegal detention (with torture) and disappearance in June 2006 of former University of the Philippines students, Sherlyn Cadapan and Karen Empeño. He was sentenced (along with two other Philippine Army officers) to a prison term of 20 to 40 years.

Palparan’s behavior, before and after the reading of the verdict, starkly provided a peak into what sort of a person he is.

Apparently, he is basically a coward. But he covers up such weakness with arrogance and belligerence.

Take, for instance, how he was brought in and out of the courtroom on that day he was convicted, as he was in every hearing of the case over four years. From the Philippine Army headquarter’s detention area (where he presumably enjoyed a sense of security), he would put on a military helmet, surrounded by a phalanx of soldiers bodily shielding him upon arrival at the courthouse.

Inside the court, while waiting for the judge to come out, he feigned self-confidence as he told a news reporter who queried him, “After this, we walk as free men. We are not guilty.”

After the court verdict was read, however, Palparan instantly transformed himself into a boor. He yelled at the judge, “Duwag ka, judge! Duwag ka, tarantado! (You’re a coward, judge! You’re a coward, jerk!).“And when the judge warned he might be cited for contempt, he shot back, “It doesn’t matter anymore. We’re going to prison anyway.”

It took quite a time before “The Butcher” was finally charged in court and put on trial.

In 2007, under strong public pressure, President Arroyo formed a commission to investigate the more than 100 cases of extrajudicial killings that occurred under her watch. Retired Supreme Court Justice Jose A.R. Melo headed the body (thus, it was called the Melo Commission). In its 89-page report, the commission pointedly recommended Palparan’s prosecution. But nothing happened.

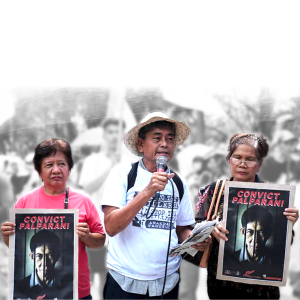

Meantime, the mothers of Sherlyn and Karen painstakingly sought recourse through petitions of habeas corpus filed with the Court of Appeals and the Supreme Court. Their efforts paid off. Aided by human rights lawyers, the mothers—Erlinda T. Cadapan and Concepcion E. Empeño—filed a complaint against Palparan and his military cohorts in May 2011.

When the preliminary hearings on the case began, Palparan tried to slip out of the country but he was stopped at the airport. After he was indicted in December 2011 he went into hiding to evade arrest. Only after he was arrested in August 2014 did the trial proceed, with many interruptions at the instance of Palparan’s lawyers.

The Butcher is now confined at the National Penitentiary (Bilibid Prison) in Muntinlupa City, among other maximum-security convicted criminal inmates. His lawyers have filed an appeal for reconsideration of the court’s verdict.

The basis of the appeal is quintessentially Palparan’s vicious anti-communist line. It asks the court to review its “erroneous appreciation of the written statement and testimonies of the [key] witness, Raymond Manalo, who is under the protection and support of the Communist Party of the Philippines.”

It was during his deployment as Army unit commander against the New People’s Army (NPA), after an eight-year assignment in Sulu to fight against the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), that Palparan consistently built up and demonstrated his utter ideological, anti-communist viciousness.

As he was promoted to higher ranks, Palparan turned more arrogant, self-righteous, bigoted, and fascistic.

His viciousness was manifested in a stream of extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, and massacres mostly victimizing noncombatant activists and civilians—as affirmed in the report of the Melo Commission. Its investigation focused on 136 incidences of extrajudicial killings (EJKs) previously verified as true by the Philippine National Police’s Task Force Usig, another probe body created by Arroyo.

At the National Consultative Summit on Extrajudicial Killings and Enforced Disappearances, initiated by then Chief Justice Reynato S. Puno in July 2007, Justice Melo made a brief oral presentation of the commission’s report. He quoted some of Palparan’s statements to the media that more than tended to acknowledge or confirm his role in the spate of EJKs.

Among those statements are the following:

“I want communism totally erased—to wage the ongoing counterinsurgency by neutralizing not just the armed rebels but also a wealth of front organizations that include leftist political parties, human rights and women’s organizations, even lawyers, and members of the clergy.”

“My order to my soldiers is that if they are certain that there are armed rebels in the house or yard, ‘Shoot them!’ It will just be too bad if plain civilians are killed in the process. We are sorry if you are killed in the crossfire.”

“Would there be some collateral damage [once the soldiers shoot]… But it will be short and tolerable. They [referring to critics of his methods] blow it up as massive violations of human rights, but to me it would just be necessary incidents. Sori na lang kung may mapatay na sibilyan (it’s just too bad if civilians are killed). The death of civilians and local officials were small sacrifices brought about by the military anti-insurgency [campaign operations].”

On the extrajudicial killings in the areas he was assigned as field commander, Palparan was more voluble and cocky. Here are some of his statements that Melo cited:

“They [EJKs] cannot be completely stopped. I would say they are necessary incidents in a conflict because they [the targeted victims] are violent. It’s not necessary that the military alone should be blamed. We are armed, of course, and are trained to confront and control violence. But other people whose lives are affected in these areas are participating [in the armed conflict].”

“The killings are being attributed to me. But I did not kill them. I just inspired the triggerman.”

“I am responsible, relatively perhaps… But in the course of our campaign, I could have encouraged people to do that—so maaaring may responsibility ako doon (so maybe I am responsible). I don’t want that aspect, but how could I prevent it? We are engaged in this conflict. All of my actuations have been designed to defeat the enemy. And in doing so, others might have been encouraged by my actions.

“Whoever it is, who could have been encouraged by my actions and actuations in the course of my campaign [against] whoever they are. That is why I say relatively. If these are soldiers, maybe then I could have been remiss in that aspect. But we are doing our best to keep our soldiers within our mandate.”

As regards the progressive party-list organizations that had won seats in the House of Representatives, whose members had become EJK victims since 2001, Melo quoted Palparan as having said the following:

“A lot of the members are actually involved in atrocities and crimes… Even though they are in government as party-list representatives, no matter what appearance they take, they still are enemies of the state.

“The party-list members of Congress are doing peace to further the revolution of the communist movement. I wish they are not here.”

“We can draw our own conclusions from these statements,” Melo told the participants in the Supreme Court-initiated consultative summit.

He pointed out that all of the victims of the 136 EJK incidents were activists, were “generally unarmed, alone, or in small groups and were gunned down by two or more masked or hooded assailants oftentimes riding motorcycles.” The assailants, he added, “surprise the victims in public places or their homes and make quick getaways.”

Also, “it is of note that the military in general called the victims as enemies of the state who deserved to be neutralized, according to the testimony given to us,” Melo added.

(Significantly, the Malolos RTC Branch 15 decision convicting Palparan also states: “Clearly, General Palparan was one [with others] in the desire to stamp out the enemies of the state, like Karen and Sherlyn, who they believed deserved to be erased from the face of the earth at any cost.”)

The investigation also established that “the PNP had not made much headway in solving the killings,” Melo said. Only 37 cases had been forwarded to the proper prosecutor’s office.

Also speaking for the House of Representatives at the National Consultative Summit in July 2007, then Makati Rep. Teodoro Locsin Jr. commended the Melo Commission Report as “complete, comprehensive and fair… and forthright in its conclusions and recommendations.”

He noted that the Melo Report says, “the signs are abundant and cannot be ignored that General Palparan had actively encouraged the men under him, in at least three areas he was assigned as field commander, to ‘neutralize’ activists tagged as ‘enemies of the state.’ ” This is a category [“enemies of the state”] that “does not exist in law, conventions of warfare or articles of war,” said Locsin, who is a lawyer-journalist.

On this point, the Melo Report concluded: “By declaring persons enemies of the state, and in effect, adjudging them guilty of crimes, these persons have arrogated unto themselves the powers of the courts and of the Executive branch of government.”

On this point, the Melo Report concluded: “By declaring persons enemies of the state, and in effect, adjudging them guilty of crimes, these persons have arrogated unto themselves the powers of the courts and of the Executive branch of government.”

“To be sure,” Locsin pointed out, (Palparan) denied ordering any killings but granted that he may have inspired the triggerman. Congress [through its Commission on Appointments] reacted swiftly confirming his promotion in time for his long-awaited retirement,” he added wryly.

“The Melo Commission pointedly recommends General Palparan’s prosecution on command responsibility: either for not stopping his men from carrying out the killings or for encouraging a climate conducive to the commission of these crimes by security agents,” the congressman noted, and he agreed with it.

And for good measure, Locsin shared that, through his questioning during a House of Representatives public hearing on the EJKs, “Palparan would not categorically deny that under his command there are special teams operating at night, wearing bonnets, or masks, with the apparent mission of extrajudicial elimination of so-called enemies of the state.”

By these accounts of Palparan’s offhand statements or replies to questions, both from the media or congressional investigations, he is totally capable of incriminating himself, whether unwittingly or wittingly—and braggingly at that! On the The Butcher’s “would-not-categorically-deny” stance, Locsin mischievously remarked, “Apparently, he feared the prospect of being charged with perjury rather than murder.”

In Duterte’s rein as the commander in chief of the AFP, Palparan would have been his perfect collaborator, joining the other Gloria Arroyo generals Hermogenes Esperon of the National Security Council and Eduardo Año of the Interior and Local Government.

Duterte is president and commander-in-chief and Palparan a mere pawn in the chain of command but, both feel they are gods in their own right, gods spawned by a debased system of class divisions.

Both Duterte and Palparan have intense abhorrence of communists and desperately dream of crushing the national democratic revolution. Both would dismiss the call for peace as a way to further the revolution. Palparan would readily smell blood (and be nourished by it) from Duterte’s order to neutralize not only armed rebels, but also activists, supporters, and “would-be rebels”. Both would arrogantly ramble of claiming full responsibility which inspire and spur killings and violence unmindful of innocent victims they dismiss as collateral damage.

Duterte may have outshone Palparan with his boorish, misogynistic remarks and acts against women as well as with his blasphemous tirades of God. But like Palparan, Duterte will suffer the same ignominious fate when the people’s wrath and justice catch up with him.

A visual artist and film director finds himself in the rugged mountains of the Cordilleras and he’s loving it. “Dati

Since 1981, when the Marcos dictatorship initiated Operational Plan (Oplan) Katatagan purportedly “to defend the state” (the besieged fascist regime)

by Erika Hernandez Neophyte Senator Ronaldo “Bato” dela Rosa, the controversial Philippine National Police chief of the Duterte government, recently