With the upsurge of youth activism in the early 70’s, Romulo Jallores, a third-year high school drop-out who did odd jobs for a living in the periphery of the university belt, was drawn to the youth organization Samahang Demokratiko ng Kabataan (SDK). He attended teach-ins and discussions of the group in reading rooms of the University of the East. He marched with them in demonstrations and protest rallies, his tall built towering over the throng.

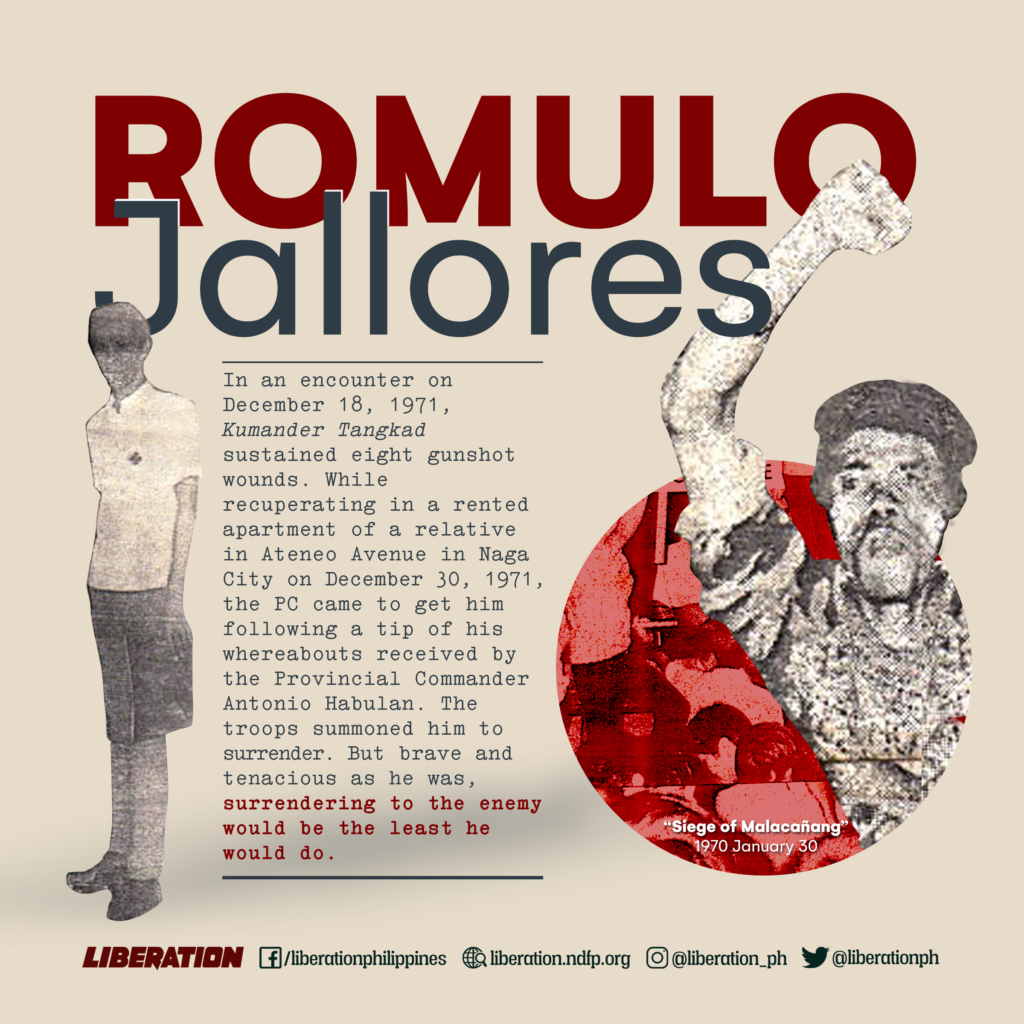

Courageous and aggressive, Romulo joined a band of youth in commandeering a truck to ram the gates of Malacañang. That demonstration of January 30, 1970 signalled the start of the First Quarter Storm (FQS). The Nation carried an article on the event entitled “Siege of Malacanang.” In the photo, among the youth on top of the truck, was Romulo wearing a beret like Che Guevara. Ernesto Che Guevara was the Argentinian expeditionary revolutionary whose name created waves not only in Latin America but also across the globe after the victory of the Cuban revolution led Fidel Castro with his help. From then on, Romulo came to be known in the activists’ circle as Che.

Courageous and aggressive, Romulo joined a band of youth in commandeering a truck to ram the gates of Malacañang. That demonstration of January 30, 1970 signalled the start of the First Quarter Storm (FQS). The Nation carried an article on the event entitled “Siege of Malacanang.” In the photo, among the youth on top of the truck, was Romulo wearing a beret like Che Guevara. Ernesto Che Guevara was the Argentinian expeditionary revolutionary whose name created waves not only in Latin America but also across the globe after the victory of the Cuban revolution led Fidel Castro with his help. From then on, Romulo came to be known in the activists’ circle as Che.

Further studies and discussions during his stint in the SDK headquarters in Taytay, Rizal deepened his understanding of the fundamental problems of the Philippine society—of imperialism, feudalism and bureaucrat capitalism. Their relation to stark realities dawned on him: the impecunious situation of their family, a brood of 10 raised solely by their mother; the discrimination he experienced in school because he was not moneyed like his other classmates; the wretched plight of the landless farmers and parahagot in the abaca fields in Tigaon, a town in Camarines Sur.

Concern and compassion for the poor and the oppressed were inherent with Romulo. From boyhood, he had always sided with the underdog—the bullied playmate or the losing one in a game. Selfless, the welfare of others was prime to him. Thus, it was never difficult for him to abide by the call to serve the people.

The high idealism and aspiration of the youth stir them to pursue the path to change, meaningful change that will uplift people’s lives, especially those of the disadvantaged and marginalized. Heeding the words of Mao Zedong, the youth set out to integrate with the masses of peasants and workers—learning from them, consolidating their ideas and experiences, arousing and organizing them, helping them achieve their emancipation.

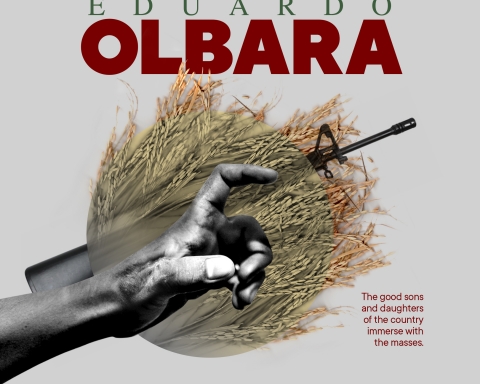

Romulo, with his elder brother Ruben and student-comrades in the movement, went back to his hometown in Tigaon, Camarines Sur. Initially, they joined in organizing a people’s movement—the Bagong Katipunan which had been short-lived. Later, they proceeded to the rural areas to immerse with the farmers and abaca workers. They helped them plant their food as they enlightened them on issues and as they organized them.

When the writ of habeas corpus was suspended in August 1971, Romulo and Ruben visited their mother to bade her farewell. That was the last time she talked and saw them.

At age 24, the country kid, who had ventured to Manila to earn for a living from odd jobs in garage and machine shop, who had become an activist thirsting for knowledge and hungering for change, had turned into a red fighter, gaining the monicker Kumander Tangkad for his over six-foot height. His brother Ruben took the name Kumander Benjie. Kumander Tangkad believed, as he had learned in the past, that only an armed revolution can liberate the people from the fetters of the semi-feudal structure that US imperialism with its local cohorts of landlord/comprador and bureaucrat capitalist foster. Resting on the creativity and strength of the masses, the people’s war erupted in the hinterlands of Tigaon.

The people rejoiced and fully supported the New People’s Army, their protector from the abusive Philippine Constabulary (PC) and bad elements who stole their carabaos. Making a dent on the control of the fascist troops in the area, the NPA was pursued like mad by the PC.

In an encounter on December 18, 1971, Kumander Tangkad sustained eight gunshot wounds. While recuperating in a rented apartment of a relative in Ateneo Avenue in Naga City on December 30, 1971, the PC came to get him following a tip of his whereabouts received by the Provincial Commander Antonio Habulan. The troops summoned him to surrender. But brave and tenacious as he was, surrendering to the enemy would be the least he would do. Mao’s quotes were ingrained in his mind, “Wherever there is struggle, there is sacrifice, and death is a common occurrence.” “Dying for the interests of the people is a worthy death.”

Using his wounds as pretext, Jallores urged them to come and get him. But as soon as the troops entered the room, they were met with fire from a .45 caliber felling PC Lt. Segundino Agahan dead. Retaliating, the PC riddled Jallores with a volley of shots. Twenty-two bullets on his body snuffed out the life of Kumander Tangkad.

But the legend of Kumander Tangkad lived on and thousands took up the rifle he dropped. The flames of the revolution kindled in Tigaon raged into a conflagration that engulfed and spread throughout the region. In due time, organs of political power were also set up in guerrilla zones.