by Priscilla de Guzman

“Kung malayo pa ang pupuntahan natin, mas malayo na rin naman ang pinanggalingan. Ituloy-tuloy na natin.”

—Ka Pidyong

“If the end of our struggle is still far away, where we started from is now much farther away. Let’s continue fighting.” —Ka Pidyong

Now 75 years old, Ka Pidyong couldn’t contain his laughter as he recalled the first time he met members of the New People’s Army (NPA) in their community, an upland barrio in Northern Luzon.

“There were seven of them,” he said in Filipino, grinning. “Only one had an armalite rifle, while the others had carbines, a shotgun, and a caliber .38 handgun— all teka-teka guns (teka literally means “wait” and refers to low-caliber guns). Of the last member of the team, he remembered vividly, “He had no gun, but carried a kaldero (a metal pot used to cook rice).”

“Three years later, they were already 16 and fully armed,” Ka Pidyong mused. “We were so happy. Our morale was high because 12 of them were recruited from our village.” Some of the original members had been redeployed elsewhere, he added, remarking enthusiastically, “They continued to grow, so did we.”

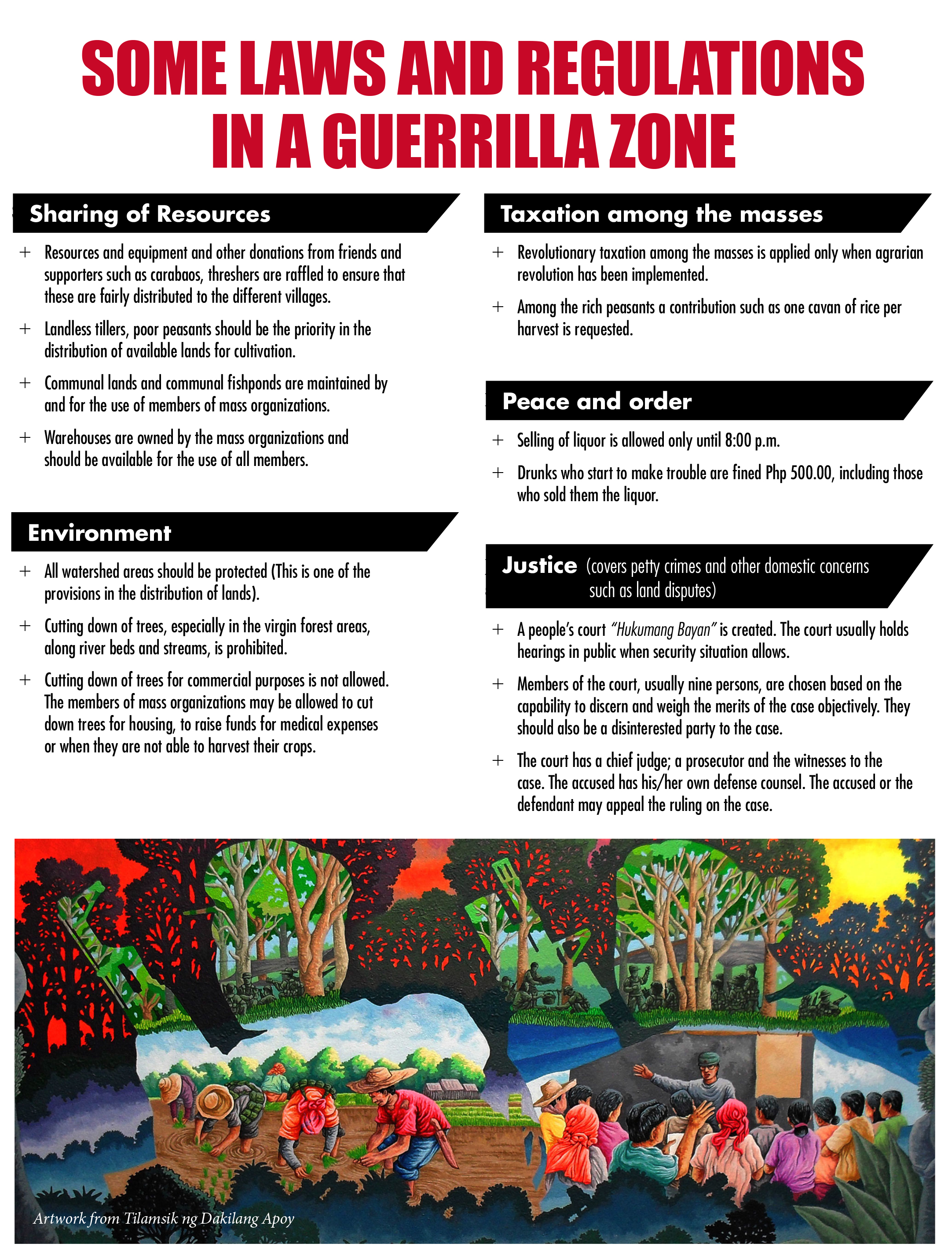

Decades after that first contact with the people’s army, the villagers have now established, painstakingly, their own organs of political power: the revolutionary mass organizations of peasants, women, and youth. A revolutionary council has also been elected and now governs their communities. In 2017, members of the mass organizations—representing the unity forged by the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), the NPA, and their allies—held their second elections in less than five years.

All these years, despite the continued military onslaughts and even during the Party’s brief period of disorientation, the organized masses did not waiver. Not even for a moment did they lose the faith that the revolution is their only hope, the future of their children, and of their children’s children.

Setting the revolutionary fire

Indeed, it has been a long, arduous, but victorious journey for those who blazed the revolutionary trail in this guerrilla zone—the first batch of peasant men and women who welcomed comrades from the CPP and NPA in 1971, when the twin revolutionary organizations were in the formative stage.

Peasant leader Ka Tonyo, 65, first met the NPA in 1971. “Na-recruit ako nung 1972, pagbalik nila sa sitio (But I was recruited only in 1972 when they returned to the village),” he told Liberation. As one of the leaders in the barrio, Ka Tonyo went with the NPA to the different mountain villages and those near the town center. They held meetings and talked to the masses. “We held education sessions and explained to them the ills of our society and the proposed long-term solution to our situation.” He said the people, aware of their own condition, readily agreed on the need to change the prevailing system and install their own government.

The peasants in this guerrilla zone are mostly landless, some tilling a hectare or two. The communities are nestled in a public land, where any moneyed individual can claim ownership over parts or all of it in blatant disregard of existing laws. All too often, the peasants had been victims of traders who preyed on them by selling farm inputs and implements that were overpriced and buying their farm produce at dirt-cheap prices. The government, too, attempted several times to evict the peasants and give way to so-called development projects, but did not succeed.

Ka Tonyo, along with woman leader Ka Gloria, and several others organized the peasants who would later comprise a chapter of the Pambansang Katipunan ng mga Magsasaka (PKM, National Association of Peasants), one of the founding affiliate organizations of the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP). Although there were already a number of organized women, Makibaka (Makabayang Kilusan ng Bagong Kababaihan) would be established in their community much later, Ka Gloria explained.

It was after a decade of organizing work initiated by the NPA and Ka Tonyo’s group that Ka Pidyong, a former barangay council member, was recruited in 1981. Ka Pidyong first learned of the NPA’s off and on presence in villages in the forest area surrounding their barrio in 1971. However, only in 1981 did he come into personal contact with them at the barrio center.

“What truly got me to realize was the fact that the Philippines is a rich country, yet only the foreigners and the local ruling elite benefit from these riches,” he said. The education session was followed by many more until, “ang dami ko nang alam (I learned so much)” Ka Pidyong said, beaming.

In between education sessions, Ka Tonyo, Ka Pidyong, Ka Gloria, and other PKM members continued house-to-house calls to explain to the masses what they had learned. They recruited members for the revolutionary mass organizations and the NPA. “Madami akong na-recruit, andito pa yung iba (I had a number of recruits. Some of them are actually still here),” Ka Tonyo proudly stated. Attending the anniversary celebrations of the CPP and the NPA was the most awaited activity by the masses—an occasion likened to a feast.

“There was always something new to do and to improve on,” said Ka Pidyong.

As the organizations expanded, they also thought of ways to tackle their revolutionary tasks more effectively, such as: how to give education to those who are not literate; how to maintain communal farms, form a militia unit in the barrios for their security, and how to efficiently support the various needs of the NPA— the latter task they took to heart most fervently. The welfare of the NPA fighters has always been at the forefront of the masses’ concerns. Even in times of calamities, when there was hardly anything to eat, the masses saw to it that there was food for the Red fighters.

On her part, Ka Gloria related, women were organized under the Makibaka, which took on other tasks for the revolutionary movement.

Makibaka members took the lead in taking care of the children of fulltime cadres and Red fighters. They looked after their schooling and overall welfare. The women, said Ka Gloria, likewise started the health and sanitation programs, which include production of herbal medicine.

The youth, she added, were organized under the Huwarang Bata (Model Youth), which initiated sports programs, among others. Ka Teody, one of the youngest leaders of the PKM, recalled that in those years, when members of the NPA came back from tactical offensives, the youth would welcome them with revolutionary songs.

Red power

Verily, today’s gains are a product of the revolutionary masses’ perseverance under the guidance of the Party and the NPA. “We have seen, however little, the difference between living under this rotten system and under the revolutionary government we are setting up.”

The revolutionary council has formalized the system of governance that was slowly established since the movement started and the masses had been organized, Ka Teody told Liberation.

Electing the new members of the revolutionary council last year was another level of consolidation achieved. “There were almost a hundred of us who attended the election, representing the various revolutionary mass organizations and party units in this guerrilla zone,” Ka Teody said. “It took us the whole day, from 9:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m.,” he explained, because “we had to go back to the orientation and tasks of the revolutionary council and the tasks and responsibilities of the officers.”

Also, they voted three times to ensure proportional representation in the council. “On the first round, we voted for eight representatives from the various mass organizations; on the second round, we elected seven representatives from the Party units, and on the last round, four representatives from the middle class in the barrio,” Ka Gloria elaborated in Ilokano. Each of the candidates, too, had to cite their individual strengths and weaknesses, thus enabling the electorate to weigh in how they could work collectively.

Through the decades, what has become undeniably visible is the people’s unity. “Where before we led our own lives without concern for each other’s welfare,” remarked Ka Gloria as she enumerated the benefits of such unity: “disputes among us are easily settled, including land disputes; the people are disciplined; the community is peaceful, there are no petty crimes.”

“The communities are drug free,” boasted Ka Tonyo.

More importantly, “we are able to thwart anti-people projects the government plans to establish here,” Ka Teody emphasized. “We now have a voice, we are no longer scared. With the NPA defending us, we can fight the oppressors,” he said.

Even the local government officials defer to the revolutionary mass organizations, he expounded. They refer cases they cannot settle to the latter organizations because the revolutionary justice system is “swift, fair, and free of charge.” Oftentimes, some local government officials would tell us, “mas kaya ninyo ‘yan (you can do it better).” (See also—story on justice system).

“There’s joy in our hearts because we are able to contribute to the resolution of the problems of the majority of the poor in our country.”

—Ka Gloria

Tempered by struggle

Leaders of the PKM identified two most trying moments they had experienced in their almost 50 years in struggle: the Party’s disorientation in the late1980’s until the early 1990’s and the intense militarization during the same period. But they held the fort, they said, never losing track of the revolution’s onward march, much more the will to push it to victory.

With pride, they recalled how they overcame the military presence and operations in their communities—aerial bombings, harassments, arrests, killings and other human rights violations. “Many were killed in the different villages,” Ka Tonyo pointed out. “But even in those difficult times, when we were almost surrounded by the enemy, we put in our hearts and in our minds where we stand—to serve the the Party and the masses.”

Ka Gloria related how, to some extent, they were able to overcome and to survive the military presence in the barrio center. “The AFP encamped at the barrio. They stayed for 14 years and in those 14 years, several organizing groups and revolutionary mass organizations were established in the communities surrounding the barrio.”

“There was fear but we were not intimidated.”

—Ka Tonyo

“No one was ever recruited into the AFP’s paramilitary unit. There were a few who almost agreed to be recruited but we persuaded them to back out,” said Ka Pidyong with a chuckle. Ka Pidyong was arrested by the military but, after his release, went into hiding several times after because of the continuing threats of re-arrest.

At the time, the NPA stayed away from the barrio center since their presence would cause unnecessary confrontation with the government forces that would affect the unarmed civilians.

But such restraint was no longer exercised during the Party’s disorientation, recalled Ka Tonyo.

“Matindi ‘yun, kawawa ang masa. Kung saang bundok kami naghahatid ng supplies, pagkain (The situation then turned intense, pitiful for the masses. We had to bring supplies, food into the remote mountainous areas where the NPA retreated after launching tactical offensives).” He was referring to the period when military adventurism seeped into the NPA ranks and mass work and agrarian reform tasks took a back seat to tactical offensives that were launched one after another.

Ka Pidyong was among those in the barrio who disapproved the swing to military adventurism, saying it was not time to show off the NPA’s military strength in their guerrilla zone. His memory of how the NPA had shifted its focus and the change in its attitude towards the masses was still fresh. “Yung mga kasama noon wala na, kapag pinupuna ayaw na (At that time the comrades didn’t want to accept criticisms).”

Sadly, Ka Pidyong was among those who were suspected as military agents within the movement during the anti-infiltration campaign. Although he had ill feelings then, now he shrugs off the whole experience. During the rectification period, the Party and NPA cadres and Red fighters humbly criticized themselves before the masses and members of the revolutionary organizations as they explained to them the rectification process.

“The elders in the community did not mince words in criticizing the Party and NPA members, which the latter wholeheartedly accepted,” added Ka Gloria.

“What is important is we have rectified the errors and we have now grown stronger.”

—Ka Teody

With the revolutionary government now in place, “we can chart our course and defend our gains,” he added.

One with the Party and the people’s army

A good number of the revolution’s trailblazers are now in their 70s, their faces lined with wrinkles and the hair on their heads turning grey or white and thinning. Still they stay in high revolutionary spirit. They have been in the movement for at least 47 years. Some of them were just about 12 years old when introduced to the movement.

“I am happy now. Despite my age and ailment, I am still able to help in whatever way I can,” Ka Pidyong remarked. He quickly added, “And, I’m energized to see young people, from our place, from other places, from the cities who come here and stay with us.”

It took several probing questions from Liberation on how these trailblazers felt about being the bearers of revolutionary power in their communities before they could answer. There was initial silence, a long silence. Tears welled in the eyes of some of them.

Clearing his throat, Ka Pidyong spoke up first. He firmly declared, “Without the Party and the NPA, we have nothing.”