by Vida Gracias

I wanted to give him a face, but this once university-educated youth who turned NPA guerrilla would rather live in anonymity. He is known simply to his comrades and the masses in the barrios as Ka Carlo.

By his looks and sun-baked skin he would appear to anyone as ordinary masa. But, when he started to talk I knew he was no ordinary fighter. What struck me was not so much his background (as more and more university students to this day—yes, under the Duterte regime–go up the hills to fight) but how he articulated his thoughts about the current regime.

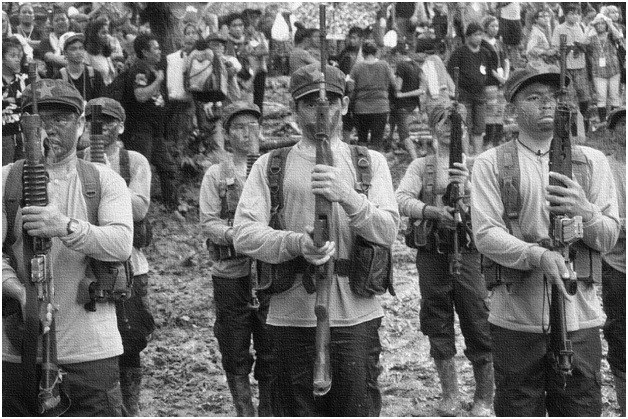

The day I met him he was wearing his standard faded jacket and a cap, his M-16 rifle slung on his side. His rain boots were caked with mud. Probably in his forties, after two decades of guerilla struggle he had seen a dozen battles, sometimes on the offense, sometimes on the defense. A bullet had torn his flesh and hit a bone and took him a year to recover. But he never waivered, he went back to the hills, and now sat on a ridge in chilly weather overlooking the vastness of the Cordillera mountains, talking about the armed struggle and the Duterte regime.

He said he had his doubts over the election of a president who claimed to be socialist and leftist. But he recognized that Duterte’s rise to power was phenomenal and rode on tremendous popular support. But he has battled too many regimes to believe everything said about the new president.

Ka Carlo was willing to give Duterte the benefit of the doubt and see what promises are fulfilled. “It is just Duterte,” he remarked, “and he is lording over a reactionary regime.” How Duterte could make true his promise of change remained a mystery to him. Especially when in the following days Duterte would flip-flop on his statements, run aground with his own words, and rant about anti-people and anti-poor programs from “tokhang” to demolitions to bombing New People’s Army (NPA) territories. Definitely, Ka Carlo made it clear he would settle for nothing less than a change in the semi-colonial and semi-feudal system that brought widespread poverty, injustice and plunder in the country.

So there would be no laying down of arms, he said firmly. There maybe times the guns were silenced, he said, just like in a ceasefire, but “you cannot trust the military.” In previous ceasefires, he explained, state troopers would take advantage of the situation and arrest comrades who were visiting their families. Most of the NPA guerrillas are farmers whose families live in the barrios.

Ka Carlo’s words rang true when the unilateral ceasefires both by the revolutionary left and the Duterte regime were withdrawn and President Duterte “cancelled” the peace talks arbitrarily and ordered the arrest of consultants of the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP) who had been freed on bail by the courts. The NPA charged the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) that during its own ceasefire had launched counter-insurgency campaigns in no less than 500 barangays within the areas of the revolutionary forces and killed activists and suspected NPA fighters. Also, President Duterte continued to hold off the release of all political prisoners that he had promised to do, through general amnesty, in the early days of his regime. The NDFP has emphasized that releasing the political prisoners would be in compliance by the GRP with the Comprehensive Agreement on the Respect for Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law (CARHRIHL).

The AFP countered with a “total war” against the NPA, a boast that rang hollow as the AFP had always threatened to do the same thing in the past—yet the NPA has survived over four decades of counterinsurgency campaigns. The AFP raised a lot of complaints and accusations over the killing and arrest of soldiers by the NPA but it kept silent over its own atrocities and violations of human rights against those they deemed enemies of the state.

Thus the fighting could definitely continue until reciprocal unilateral ceasefires were to be declared before resuming the peace negotiations in the first week of April. “You cannot leave the masses defenseless, even when there are peace talks,” Ka Carlo stressed. The ceasefires would remain interim or temporary for as long there is no resolution to the armed conflict. No bilateral ceasefire agreement could be forged during the peace negotiation that would only lead to the surrender or pacification of the armed movement. The negotiation could proceed but the matter of attaining just and lasting peace would ultimately hinge on the strength of the revolutionary forces on the battlefield as well as their mass support.

I stared at Ka Carlo’s battle scars and counted the years he had been fighting. The Duterte regime, I concluded, would be up against fighters with such deep resolve for change that nothing can draw them away from battle except genuine change itself.