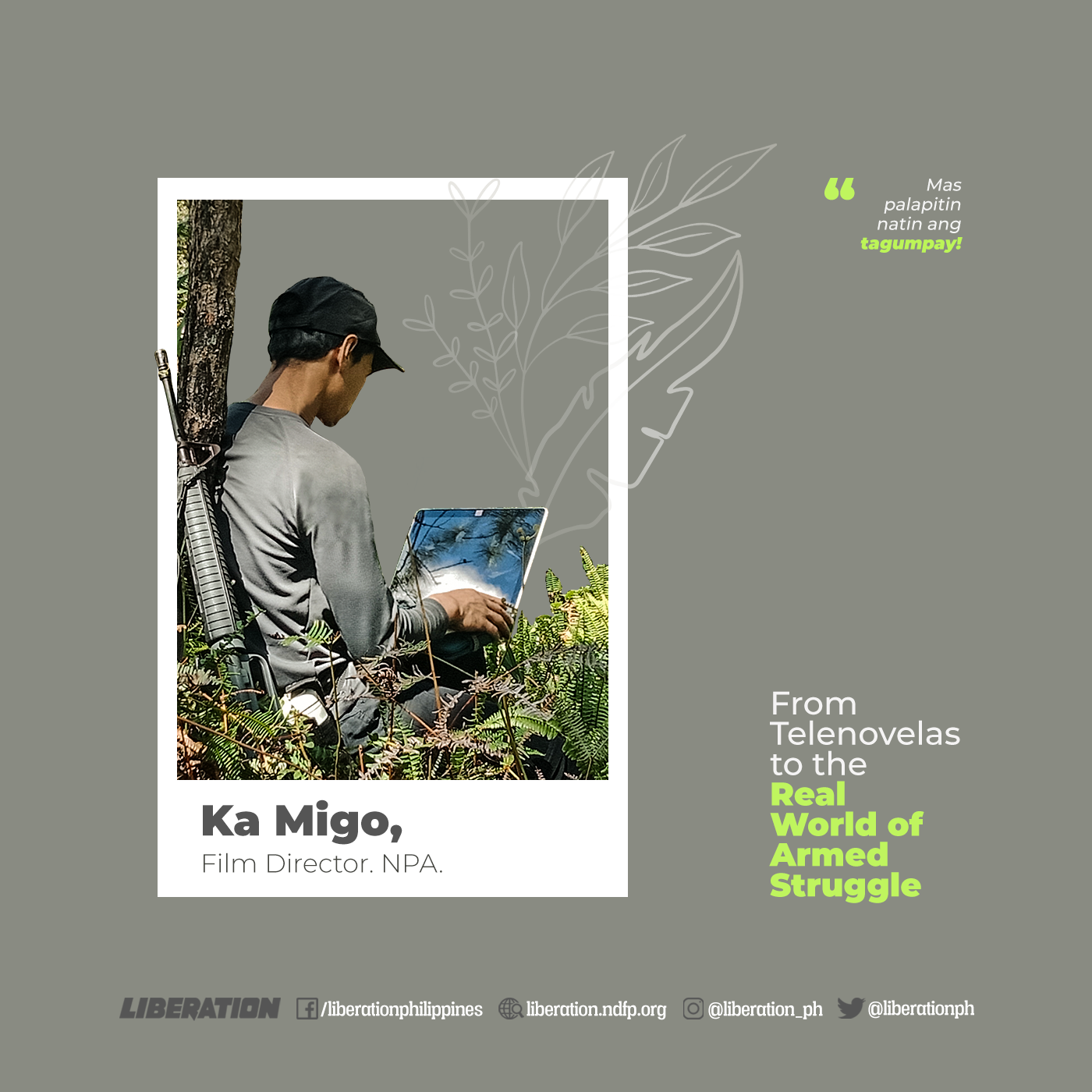

From Telenovelas to the Real World of Armed Struggle

A visual artist and film director finds himself in the rugged mountains of the Cordilleras and he’s loving it. “Dati teleserye lang, kathang-isip. Pero ngayon, ito ang totoong buhay (Before I was just into telenovelas, fiction. But now, this is for real. This is real life),” Ka Migo quipped.

He acknowledged he was never a serious activist as a young man. Although, as early as 1999, he was already a member of the Kabataang Makabayan (Patriotic Youth, a founding member organization of the National Democratic Front of the Philippines [NDFP]), it was only almost after a decade, in 2008, that he joined a formal collective. In between those years, he was studying and at the same time into “racket”, accepting various projects for a fee. There were few times though when he would join rallies to document the event “but not as an active participant”, he claimed.

Through a wide-angle lens

The disappearance of UP students Karen Empeño and Sherlyn Cadapan and the testimony of the case’s witness Raymond Manalo, who was also a political prisoner who met the two in the detention center, was a turning point for this artist. He was, he recalled, stunned to learn that a “concentration camp” existed in our midst— where activists were brought and killed. “Civilian lang pero kapag napaghinalaan tinutuluyan na nila dun. ‘Yung kwento ni Manalo parang nasa Nazi concentration camp (The civilians once suspected were finished off in that place. Manalo’s story depicted that of a Nazi concentration camp.)”

While this artist firmly believes in the power of video to educate people, it was just that. It was only after he learned of the circumstances of the disappearance of the two students and how they were tortured and molested by the military that he seriously considered going into documentary films on social issues.

In 2009, a year after he took his basic Party course, he decided to join the New People’s Army (NPA). Having skills in film making, he expected it would be one of his tasks. But the NPA unit where he was assigned only learned about his artisty much later, which he said, worked in his favor.

No cuts, no edit

It was to his advantage that Ka Migo was able to immerse with the masses, do territorial work and participate in tactical offensives, “all the elements of the work in the countryside—armed struggle, base building and agrarian revolution.” The experience enriched him as a Party cadre and a red fighter.

While deep into the work in the countryside, Ka Migo realized that if only the public could see what the people’s army is actually doing then they would start to appreciate the importance of armed struggle—realistic telling moments that would definitely touch the hearts of the masses, the youth, and professionals in urban centers. “Ito yung katotohanan, na yung tao, dahil sa pagsasamantala, talagang lalaban yan, at ito yung isang itsura niya, yung armadong pakikibaka.”

This is the stark reality. Exploitation impels people to fight back through armed struggle.

Armed struggle it is. Life in the guerrilla zone affirms what Ka Migo studied in Party courses that armed struggle is the primary form of struggle. “My experience showed me how effective and important it is.”

He talked of the political power the NPA holds in the villages over the enemies of the people, which he quickly attributed to Comrade Mao Zedong’s adage, “political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.” Erring companies, for example, operating within the guerrilla zone, would cower in fear or in respect. Wala ka pa ngang sinasabi, naka-Sir na agad yung mga guard (Even without saying a word, the guards are quick to address them, ‘Sir’).”

Comparing this to filmmaking, Ka Migo explained, “When doing a documentary, the camera is the main weapon to depict how people are exploited and oppressed. You may criticize and warn the perpetrators with your films but it remains their choice to take action. But if you have a gun, you can actually restrain the perpetrators and make them account for the wrongs they committed.”

But the combination of the two—the camera and the gun—is most powerful. “Kung ipinapakita mo ang ginagawa ng armadong pakikibaka, na totoo ito, na ito ang dapat nating gawin tapos makikita ang iba’t ibang scenario ng paglaban ng tao para ipagtanggol ang kanilang karapatan, mas powerful yun (When you are able to show that the armed struggle is real and we all should engage in this; and you show various scenes of how people fight back to defend their rights, this is most powerful.”)

Without saying it, Ka Migo finds himself in the same scene with an artist he met in the Cordilleras—Ka Libre, whose real name is Artus Talastas. He was a revolutionary martyr who was killed in 2014 in a firefight with the military. He was a red fighter, a commander of the NPA. He was also a painter and a musician. He is known in many villages because he gamely indulged those who wanted a sketch of themselves or their families. His songs, mostly in the form of saliddumay (local folk song), talked about the people’s struggles.

Composing the future

Ka Libre always told Ka Migo, “Nandito ang materyal sa paglahok sa digmang bayan. Makisalamuha ka sa magsasaka at manggagawa para ma-portray natin sila, yung kanilang pakikibaka, yung armadong pakikibaka ng malawak na masa, kung gaano ito kawasto at totoo at dapat na ginagawa ng nakararami.”

You get your material from your participation in the people’s war. Integrate with the peasants and workers so we can portray them,their struggles, the armed struggle of the broad masses of people and to show how just and true it is and that more people should engage in this.

In Ka Migo’s 10 years in the people’s army, he has cherished Ka Libre’s words. Paraphrasing him now, Ka Migo called on the artists and cultural workers, “Pumunta tayo sa sona, andito yung material para sa armadong pakikibaka, yung pinakamataas na antas. Heto sana yung gamitin nating inspirasyon ng kahit ano’ng sining natin (Come to the guerrilla zones, the material for and on the armed struggle is here, in its highest form. Let’s use this as our inspiration for our art).”

Know, learn, and muster inspiration from the life experiences of the masses, the people’s army and their lives together in the guerrilla zone to compose songs, paintings, poetry and literature. Ka Migo’s words ring true in the heart of every revolutionary artist. “Mas palapitin natin ang tagumpay (Let’s push forward to victory),” Ka Migo said as he uses his camera and his gun to serve the revolution.

ServeThePeople

RevolutionaryArt

JoinTheNPA

VISIT and FOLLOW

Website: https://liberation.ndfp.info

Facebook: https://fb.com/liberationphilippines

Twitter: https://twitter.com/liberationph

Instagram: https://instagram.com/liberation_ph

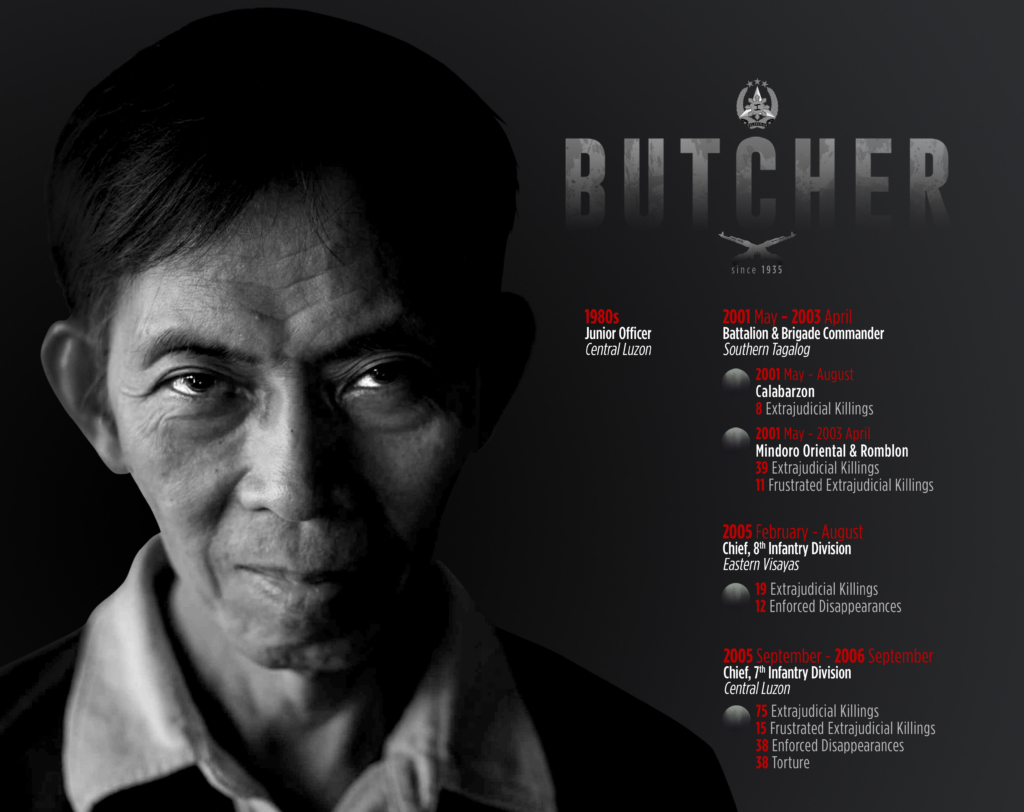

On this point, the Melo Report concluded: “By declaring persons enemies of the state, and in effect, adjudging them guilty of crimes, these persons have arrogated unto themselves the powers of the courts and of the Executive branch of government.”

On this point, the Melo Report concluded: “By declaring persons enemies of the state, and in effect, adjudging them guilty of crimes, these persons have arrogated unto themselves the powers of the courts and of the Executive branch of government.”