Peace (Talking) Heads [Part 3 of 3]

by the Liberation Staff

An Interview with Satur Ocampo, Luis Jalandoni, and Fidel Agcaoili

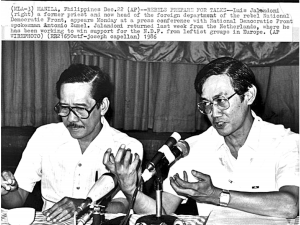

Through the decades of the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP) engagement with the Government of the Republic of the Philippines (GRP) across the negotiating table, its peace panel has been successively headed by three of the movement’s comrades of unquestionable integrity and reliability—Satur Ocampo, who headed the first negotiating panel in 1986; Luis “Louie” Jalandoni who was chief negotiator from 1994 up to 2016; and, its current chief, Fidel Agcaoili who took over in 2016 when Jalandoni resigned. The three comrades, along with the other members of the peace panel, have become the personification of the NDFP through the highs and lows of the peace negotiations.

The peace negotiating panel serves as the channel and articulator of the positions defined by the leadership of the revolutionary movement. The panel members, especially the chief negotiator, are the face and the voice of the movement.

Liberation sought the three comrades to get their views on the regimes they have dealt with either as panel heads, panel member or as an “observer”.

Ka Louie Jalandoni and Ka Fidel Agcaoili were interviewed two weeks before the scheduled fifth round of talks, which the GRP cancelled in May 2017. Ka Satur Ocampo was interviewed in June, a week after the fifth round of talks was cancelled. The interview dates should be noted as they provide the context of their responses.

Since the interview, several events have already transpired. These events include the cancellation of the back-channel talks scheduled in July before Duterte’s second State of the Nation Address (SONA), the consequent threat to terminate the peace talks and the withdrawal of bail granted to former political prisoners who are participating in the talks as consultants, the extension of martial law in Mindanao, and the threat to bomb Lumad schools, among others. (Louie Jalandoni added his comments on these events in his interview.)

During their separate interviews, the three recalled what each thought was a historic moment in the talks, their frustrations and hopes, lessons and insights in dealing with the various GRP regimes, which also reflected the shifts in the peace negotiations.

From the point of view of the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP), the peace negotiations with the reactionary government are deemed as part of the total conduct of the revolutionary struggle – which essentially is “a struggle for just and lasting peace because it strives to solve the fundamental problems of the people”. Which is why, since 1986, the mutually agreed starting point of the GRP-NDFP peace talks has been to “address the root causes of the armed conflict”.

Satur Ocampo, first NDFP Peace Panel Chairperson, 1986

FIDEL AGCOILI

Liberation: What are your thoughts as the new Chair of the NDFP peace panel?

Fidel Agcaoili (FA): Ay, naku! (Laughs). Additional work. Oo, talaga. I never expected this. In fact, when the idea was broached to me, I said no. I am actually more comfortable doing side negotiations or talks, what has come to be known as the cigarette breaks.

Now, I face them (the GRP panel) across the table as chief negotiator but still do the shuttling between the GRP and the NDFP panels to thresh things out. But, it’s good that other panel members and consultants are there to help guide me. Also, as panel chair, I am able to mobilize the peace panel staff fully, and they are all performing well. It’s good, di ba, to see your second generation doing their tasks well.

L: How are you after several months of being the Chair?

FA: Ay, talaga, pagod (Tired). Sometimes, I wonder where I get my energy. Siguro, adrenalin. The thought that the work should be done, that work should not stop until it’s done.

L: How did you feel when Ka Louie (Jalandoni) brought up the idea of resigning as chief negotiator?

FA: Oo. Yun na talaga. It was the third time he brought up his resignation as panel chair. After three tries (laughs) we needed to finally decide on Ka Louie’s request. Ka Louie was firm. And there was no way that he would want another extension. He is already 81, although he is still very sharp. The question is ‘why me?’ Bakit ako? But I guess it’s because I am the most senior among the remaining panel members.

L: Going back to the moment when it was finally decided that you would replace Ka Louie as chair…?

FA: Overwhelmed, overwhelmed talaga. I know it was going to be a lot of work. I was also concerned with how I could balance the role of talking with the GRP panel as chief negotiator and at the same time serve as the bridge between two panels outside of the formal negotiations to reach mutually satisfactory points of agreements. Eventually, with practice, I’ll achieve that balance. But as of now, it’s difficult.

L: How long have you been a panel member?

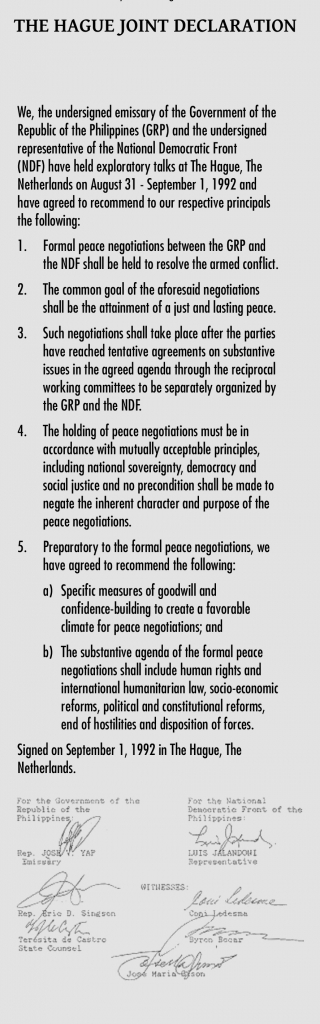

FA: Officially? I started in 1994. Louie was with the panel right from the start. Although in 1992, I was present in the deliberations on The Hague Joint Declaration, but I had no direct participation. I joined in 1994, when the talks resumed after two years of hibernation. After the signing of The Hague Joint Declaration, Pres. Ramos pushed for the NUC (National Unification Commission) headed by the late Atty. Haydee Yorac. But when the NUC had made no progress, Ramos decided to resume the peace talks. That was the time I joined the panel. The discussions then were first on the Breukelen Joint Statement, then on the JASIG (Joint Agreement on Safety and Immunity Guarantees).

L: Did you foresee that you would eventually be the revolutionary movement’s chief negotiator?

FA: No. But I was the NDFP emissary in initiating the 1986 talks. I was designated to talk with then Executive Secretary Joker Arroyo on how to start the peace negotiations and how to compose both panels. I went to Malacañang twice. I also talked with Ka Pepe (Diokno) who was the first GRP panel negotiator.

L: How would you characterize each regime you dealt with in the peace negotiation?

FA: In the case of the Cory Aquino regime, when she initiated the peace talks she was not in full control of the government. Her heart might have been in the right place in wanting to engage in peace talks with the movement, but the military and her economic advisers were against it. So, she demanded a ceasefire before negotiations and agreements on substantive issues. And the movement acceded despite the arrest of Rodolfo Salas and the killing of Ka Lando Olalia and Ka Leonor Alay-ay. A ceasefire was put in place even before any substantive agreement could be forged.

With Fidel Ramos, ah, that was surprising. He was, together with the military, the spoiler during the time of Aquino. Yet, in less than four months after taking power, he sent an emissary (a team actually) to The Netherlands to negotiate and sign the framework agreement for the peace negotiations which came to be known as The Hague Joint Declaration. Two years later, he formed his counterpart negotiating panel that worked out the other agreements on safety and immunity (JASIG), on ground rules for the formal talks, and on the sequence and operationalization of the reciprocal working committees. We even finished the negotiations and signing of the Comprehensive Agreement on the Respect for Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law (CARHRIHL), the first item in the substantive agenda.

With Estrada, ah, the peace talks were short lived. He terminated the negotiations and declared all-out war against the revolutionary movement. But this came after he had approved the CARHRIHL, as the principal of the GRP panel, together with Mariano Orosa, the principal of the NDFP panel.

Despite recognizing the role of the Left in putting her in power, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo eventually became a hostage of the military, which carried out the brutal and bloody Oplan Bantay Laya 1 and 2 that resulted in hundreds of extrajudicial killings, disappearances, forcible displacements of communities, arrests, torture and detention of activists and suspected NPA supporters and sympathizers.

But to Arroyo’s credit, she gave life to the CARHRIHL by approving the establishment of the offices of the Joint Monitoring Committee (JMC) to monitor the implementation of the Agreement. Together with human rights and lawyers groups, the NDFP section in the JMC was instrumental in opposing and exposing the campaign of extrajudicial killings and disappearances by the Arroyo regime.

Under Noynoy Aquino, there was nothing, no movement at all in the peace talks. Cacique kasi, walang alam kundi ang mag-video game at pangalagaan ang class interests ng kanyang pamilya (he knows nothing except playing video games and protecting his family’s class interests). Also, the social democrats were most influential on him, ideologically. His regime tried to undermine the major agreements signed during the Ramos regime: considering The Hague Joint Declaration as a document of perpetual division; the JASIG as a one-sided agreement and therefore inoperative; and the CARHRIHL as an NDFP document which has been superseded by the GRP’s laws. But it backpedalled on the CARHRIHL because the AFP had received funding from the European Union for trainings on the implementation of the CARHRIHL.

Now, with Digong (Duterte), there have been advances in the socio-economic reforms like the free distribution of land to the farmers. He promised to stand by it, panindigan ko yan, he said.

L: Which regime was the most difficult to deal with?

FA: Eh syempre, the most difficult to deal with was the Noynoy Aquino regime. At times, I wanted to tell them “putris kayo”, hahaha. Yes, I used the term balasubas (double-faced, cheat). Talagang ganun eh, balasubas. The Aquino regime wanted to negate the Hague Declaration, the JASIG. As concrete example, they committed to release political prisoners, in the presence of the Norwegian ambassador. Atty. Alex Padilla (then head of GRP peace panel) said they would release Tirso Alcantara, Alan Jazmines, and three more to get us back to the negotiating table. But, nothing happened. The political prisoners were not released. Eh, balasubas talaga, di ba?

L: Which regime is the most challenging?

FA: Challenging? This government (Duterte). Because we don’t know where Duterte is heading. It is mixed up and confused. But we need to push while always being prepared and vigilant. We need to push for maximum reforms and see how far we can go. Let’s see. That’s why it’s challenging. We need to get the necessary reforms for the benefit of the people, for the country to develop and advance. But we are also aware that he has his own interests, his class interests. Hence, the need for vigilance and preparedness.

L: The issue of ceasefire has always been an obstacle in the peace talks and you have consistently refused going into it before any social and economic reforms for the people are secured. Why did you entertain it this time?

FA: We went into a ceasefire as a sign of goodwill. But it was unilateral, that’s why it lasted up to six months. In a unilateral ceasefire, both sides have separate premises and you can decide anytime to terminate your declaration, especially when the people are on the receiving end of repression.

But a joint ceasefire is difficult because it binds you unnecessarily. Although we are not closed to considering this. The ceasefire the government wants could be the truce after the CASER and CAPCR were signed.

Until the fourth round of formal negotiations, we exercised flexibility, especially on the issue of ceasefire. But we cannot allow that to go on. I have told my counterpart in the GRP, Sec. Bebot Bello that they won’t get a joint ceasefire until the discussions on the social and economic reforms move forward. The GRP has been dribbling the discussions on the socio-economic reforms. One moment they would agree to a discussion on the ARRD (agrarian reform and rural development) then in an instant they would renege; the same with the discussions on NIED (national industrialization and economic development). They kept delaying the discussions on these two important parts of the social and economic reforms at the same time insisting on a ceasefire. I frankly told Bebot that we want agreements on reforms first.

L: Did Louie give you advice when you assumed the chairmanship?

FA: Ah, he said “try to moderate…” you know, there are times when I flare up even across the table. Eh, I am not really a diplomat. I am more, like I shoot from the hip, without thinking. Well, not really without thinking because there’s a wealth of knowledge gained from the many years in the movement, you know the principles, the policies and what’s happening on the ground. So you know when one is saying or doing something wrong. But I know, I just can’t shoot from the hip. Louie’s advice was helpful. I need to be a little more circumspect, which I am not. I thanked Louie. Of course, I am the chief negotiator now.

L: What qualities of Louie would you want to carry on as chief negotiator?

FA: Patience, patience, and his eloquence, di ba? I would really want to acquire those qualities. (Laughs).

L: Where do you think the peace talk is heading? What are your personal wishes?

FA: My wish is that we could sign an agreement within the year. We’ve already agreed on the framework of free distribution of land to the landless farmers. The GRP will have to give that through their own mechanisms, like legislation. Any such agreement is welcome. Then we can push this and fight for this on the streets, in the countryside and show it can be done.

That should also be the case on national industrialization so we can turn our mineral resources into finished products and then transform our economy. That’s what we are after. Let’s see.

But whatever happens, the NDFP should be ready with its own version of the CASER which we can circulate—our program in banking and finance, all the reforms we are proposing so the country can get out of the neoliberal paradigm.

L: So you were still in jail when Ramos became president?

L: So you were still in jail when Ramos became president?

Recognizing the Judicial and Legal System of the Reactionary Government

Recognizing the Judicial and Legal System of the Reactionary Government