by the Liberation Staff

An Interview with Satur Ocampo, Luis Jalandoni, and Fidel Agcaoili

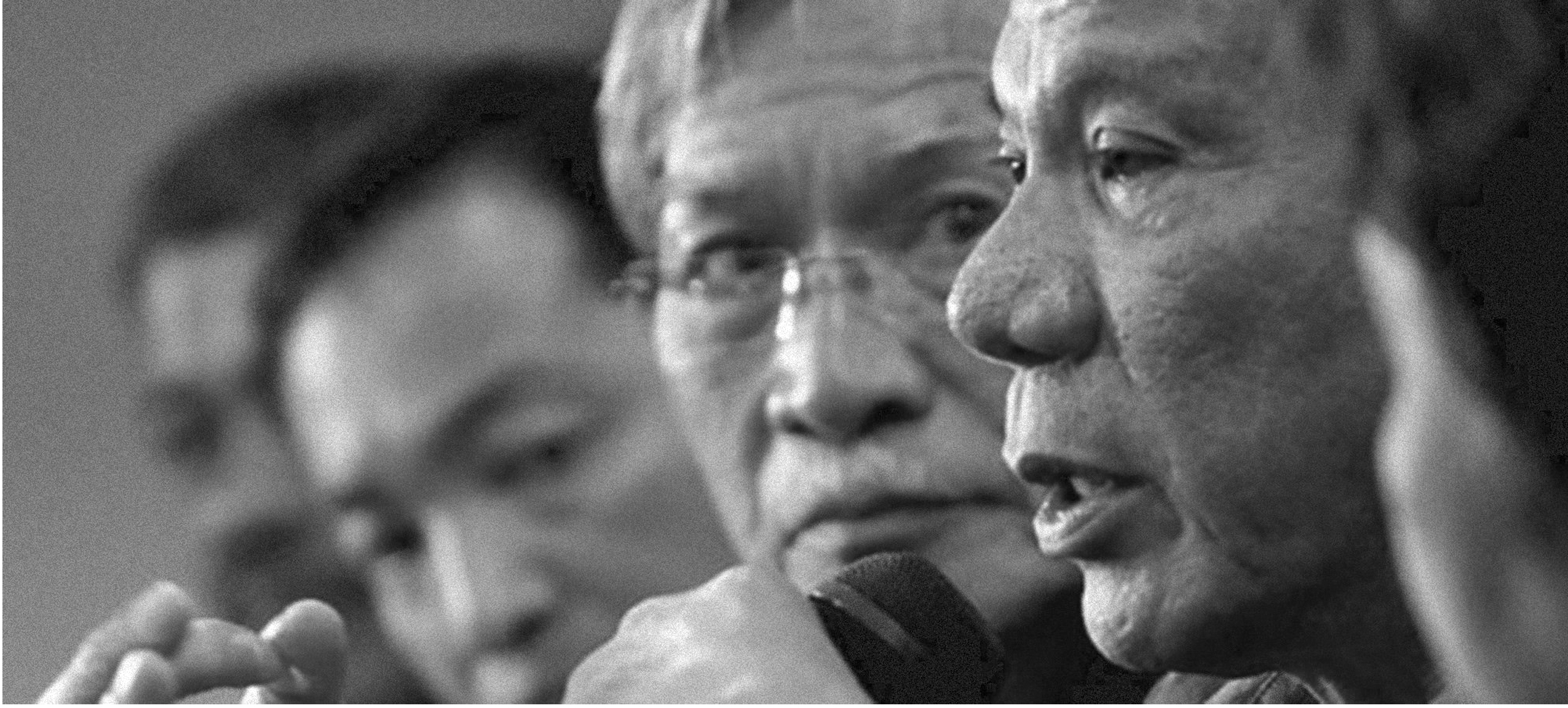

Through the decades of the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP) engagement with the Government of the Republic of the Philippines (GRP) across the negotiating table, its peace panel has been successively headed by three of the movement’s comrades of unquestionable integrity and reliability—Satur Ocampo, who headed the first negotiating panel in 1986; Luis “Louie” Jalandoni who was chief negotiator from 1994 up to 2016; and, its current chief, Fidel Agcaoili who took over in 2016 when Jalandoni resigned. The three comrades, along with the other members of the peace panel, have become the personification of the NDFP through the highs and lows of the peace negotiations.

The peace negotiating panel serves as the channel and articulator of the positions defined by the leadership of the revolutionary movement. The panel members, especially the chief negotiator, are the face and the voice of the movement.

Liberation sought the three comrades to get their views on the regimes they have dealt with either as panel heads, panel member or as an “observer”.

Ka Louie Jalandoni and Ka Fidel Agcaoili were interviewed two weeks before the scheduled fifth round of talks, which the GRP cancelled in May 2017. Ka Satur Ocampo was interviewed in June, a week after the fifth round of talks was cancelled. The interview dates should be noted as they provide the context of their responses.

Since the interview, several events have already transpired. These events include the cancellation of the back-channel talks scheduled in July before Duterte’s second State of the Nation Address (SONA), the consequent threat to terminate the peace talks and the withdrawal of bail granted to former political prisoners who are participating in the talks as consultants, the extension of martial law in Mindanao, and the threat to bomb Lumad schools, among others. (Louie Jalandoni added his comments on these events in his interview.)

During their separate interviews, the three recalled what each thought was a historic moment in the talks, their frustrations and hopes, lessons and insights in dealing with the various GRP regimes, which also reflected the shifts in the peace negotiations.

From the point of view of the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP), the peace negotiations with the reactionary government are deemed as part of the total conduct of the revolutionary struggle – which essentially is “a struggle for just and lasting peace because it strives to solve the fundamental problems of the people”. Which is why, since 1986, the mutually agreed starting point of the GRP-NDFP peace talks has been to “address the root causes of the armed conflict”.

Satur Ocampo, first NDFP Peace Panel Chairperson, 1986

SATUR OCAMPO

Liberation (L): How was your experience during the first peace negotiations in 1986?

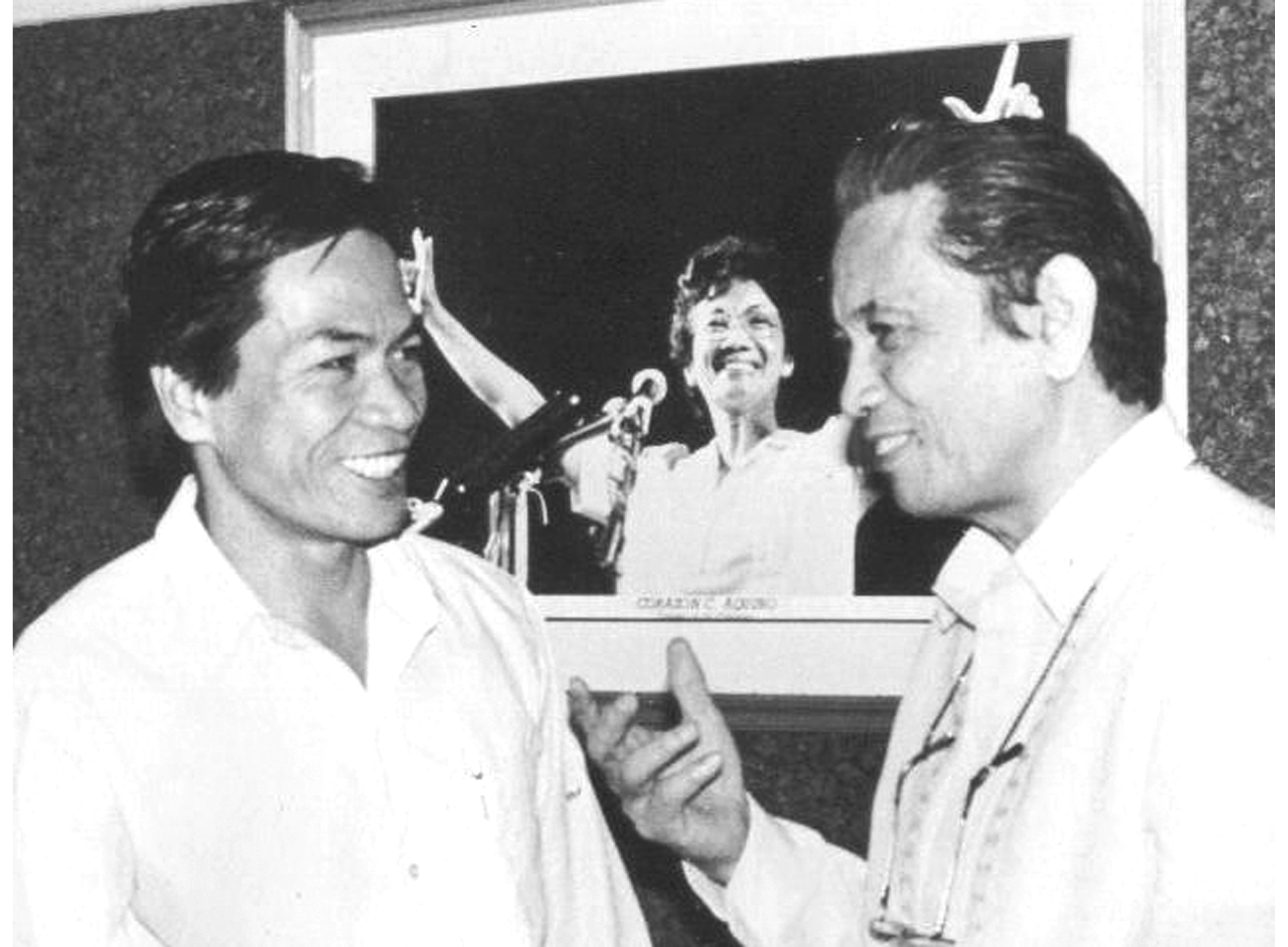

Satur Ocampo (SO): In the 1986 peace negotiations, the revolutionary movement was at its peak strength. The overthrow of the Marcos dictatorship and the popularity of the Cory Aquino regime served as the impetus for talking peace. Cory Aquino initiated the talks. In a speech at the University of the Philippines, she declared she was ready to end the prolonged internal war by addressing the roots of the armed conflict through peace negotiations.

As the NDFP spokesperson at the time, I responded that, in representation of the entire revolutionary forces, the NDFP was prepared to talk on the basis of addressing the roots of the armed conflict. Thus, at the initial meeting, the NDFP panel—consisting of myself, the late Antonio Zumel, and Carolina “Bobbie” Malay—submitted a comprehensive proposal which gave a brief discussion of the historical context of the armed conflict, defined the social, economic, and political problems underlying the conflict, and urging negotiation points on how to resolve these problems.

L: What happened to the proposal?

SO: It appeared that the new government was not prepared. The GRP panel first counter-offered a six-year medium-term development plan, which the NDFP deemed as inadequate. The problems we wanted to tackle were deep-going and far-reaching, well beyond the term of any single administration.

We were unable to agree on a substantive agenda for negotiations, due to intervening events that cut short the peace talks. We were only able to formally negotiate and sign an interim (60 days) ceasefire agreement upon the insistence of President Cory Aquino. But the ceasefire did not work out well due to differences on how it should be implemented. Our formal panel meetings got bogged down in discussing the cascade of complaints of ceasefire violations from both sides.

But that initial, informal exchange of documents set the norm for the future peace talks. With every regime, the NDFP has pushed comprehensive proposals that would address the economic, social, political, and cultural demands of the people, and the GRP has had to respond to these. In effect, the NDFP set the agenda of the peace negotiations.

L: Since 1986 up to the present, the issue of a ceasefire has taken the center stage of the GRP-NDFP negotiations despite the proposals for reforms.

SO: Ah, that’s the spoiler. The peace talks are now in peril because of the ceasefire issue.

When we examined peace agreements between revolutionary movements and reactionary governments in other parts of the world, we noted that reactionary governments have invariably adopted a common position: use the ceasefire accord to first demobilize the revolutionary army, then pressure or convince the revolutionary movement to pare down its proposals on the negotiating table, finally drive it towards capitulation. The usual consequence was that the revolutionary movements ended up shortchanged on their demands for basic reforms.

L: How was your experience during the 1986 negotiations when there was a ceasefire?

SO: First, we should understand the context of the 1986 negotiations. It should be noted that the underground revolutionary movement, and the open democratic mass movement that developed in the 80s onward, played a big role in politically isolating and weakening the Marcos dictatorship. But, when the dictatorship was overthrown, the former implementers of martial law—Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile and AFP Vice Chief of Staff Fidel Ramos, who joined the so-called people power uprising and were hailed as heroes—were appointed by Cory as defense minister and AFP chief, respectively. The duo virulently, publicly opposed the peace negotiations.

There was thus the issue of security for the NDFP panel and all those assisting us. At the time, the revolutionary movement had no solid international network yet. It didn’t cross our minds to hold the negotiations abroad to ensure our physical safety. When the negotiations started the panels agreed, in principle, to alternately hold the talks in the revolutionary base areas and in the venues chosen by the GRP. But even on the side of the revolutionary forces, there was difficulty in implementing this arrangement. We ended up holding the talks in the Metro Manila area, without the safety guarantees, now provided by the JASIG (Joint Agreement on Safety and Immunity Guarantees). We only had a government-issued safe conduct pass.

Before we could start the formal talks, Cory insisted on first forging a ceasefire agreement ahead of the discussions on the agenda. We opposed, but the pressure was strong. Certain allies in the anti-dictatorship movement who were in the new government supported the call for a ceasefire. We had to accede to the call.

The ceasefire began on December 10, 1986. It was also the start of the peace talks. On the part of the NDFP, a kick-off ceremony was held in one of the barangays within a guerrilla zone in Bataan, adjacent to the town center. When we got off our bus, the NPA had assembled an oversized squad of honor guards right at the plaza. Because the ceasefire agreement had a provision that no NPA Red fighter should enter such public place, the GRP ceasefire team accused the NDFP of violating the agreement.

L: What happened to the substantive agenda?

SO: The ceasefire implementing guidelines were not clearly defined. The only thing explicitly stated was that there should be no armed clashes between the two sides. The NPA fighters would hold on to their arms, but stay within their usual areas. However, Ramos issued guidelines that stated all areas in the country were under the jurisdiction of the GRP and its security forces had the right to patrol these areas. The guidelines also said the state forces were the only ones authorized to hold firearms. Thus, when the military entered the guerrilla zones and encountered the armed NPA units, they demanded that the latter surrender their arms. The NPA resisted, which resulted in many firefights between the NPA and the AFP.

The negotiating panels never had the opportunity to start discussions on the substantive agenda because of these ceasefire violations. Even after these had been passed on to the bilateral ceasefire teams, discussions on the substantive issues could not take off. There arose threats to the security and lives of both panels, reportedly from the Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM) loyal to Enrile. When an opportunity came for the panels to discuss the NDFP proposed agenda and the one drawn up by former Sen Jose W. Diokno (the original GRP panel chair who was stricken with and not long after died of cancer), with the theme “Food and freedom, jobs and justice”, the Mendiola massacre happened and disrupted the ongoing talks.

With the uncertain security situation, the panels agreed to suspend the talks and attend to each other’s safety. The NDFP panel went back to the countryside. We issued a statement urging continuation of the peace talks but got no response whatsoever from the GRP.

L: That was the end of it?

SO: From 1987 to 1989, I remained the NDFP spokesperson. Bobbie and I continued to work for the resumption of the peace negotiations through our allies in the different churches, both Catholic and Protestant. Meantime, Tony Zumel slipped out of the country and joined the NDFP delegation in The Netherlands. In one such mission, on August 29, 1989, Bobbie and I were intercepted by a police intelligence team in Makati. We were arrested, detained and charged with three trumped-up, nonbailable criminal offenses: murder, kidnapping, and illegal possession of firearms.

President Cory Aquino did try to resume the peace talks, sending the late Congressman Jose “Mang Apeng” V. Yap as emissary twice to the NDFP leaders in exile in The Netherlands. The latter welcomed the initiative and expressed readiness to resume the talk should the Cory government junk the extension of the US-RP military bases agreement, which at the time was being discussed in the Senate. But those efforts went to naught as Ramos, then defense secretary, and the military opposed the continuation of the talks.

L: Until Fidel Ramos became president?

SO: Surprisingly when Ramos became president, he sent Congressman Yap to be his emissary to the NDFP. Yap’s mission led to the signing of The Hague Joint Declaration (THJD) on September 1, 1992. Coincidentally on that same day I was released from military detention at Fort Bonifacio.

To his credit, Pres. Ramos did not insist on a ceasefire. The talks progressed as fighting on the ground continued. Despite repeated suspensions, the panels produced 10 signed agreements including the JASIG and the CARHRIHL (Comprehensive Agreement on Respect for Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law). The ceasefire issue was resurrected under the Duterte presidency. It has remained a troublesome issue up to now.

L: So you were still in jail when Ramos became president?

L: So you were still in jail when Ramos became president?

SO: Yes. Ramos’ changed attitude towards pursuing the peace talks and the Congress repeal of the anti-subversion law upon his initiative, in some way, helped in my release. But the key factor was that the courts cleared us of the trumped-up charges. Bobbie was released ahead of me in November 1991.

I joined the open democratic mass movement and partly went back to journalism after my release and had not been officially involved in the peace negotiations. But the media often sought my views on the developments of the peace negotiations, probably because I have been indelibly identified with the NDFP as its national spokesperson and first chief peace negotiator. The image of being “the face of the NDFP” has stuck. I was also often invited to speak at public forums on the peace talks.

L: From someone who is outside the negotiating panel, which regime do you think did the NDFP had the most difficulty?

SO: Ang pinakamaganit (most difficult) was the P-Noy government. Not only was P-Noy laid-back and hands-off, unlike Ramos, he was also was adversarial. And he appointed a social democrat, who harbored a bitterly anti-communist position, as his peace adviser and overseer of GRP panel in the peace negotiations.

The second Aquino regime opted to focus on and complete the peace negotiations with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). But when Aquino was pressured to stand by his electoral promise to resume the peace talks with the NDFP, he appointed Alex Padilla to head the GRP negotiating panel. Formerly associated with the progressive mass movement, Alex consulted me about P-Noy’s offer before accepting it. He said he was interested because he wanted to help.

I advised Alex to talk with P-Noy, to level off with him on what to do regarding the peace talks. “If you don’t agree, there’s no point in accepting the offer,” I said. Should he accept, I pointed out that as chief negotiator, he would be the President’s plenipotentiary representative and ought to directly report to and consult with the latter and not go through any intermediary, such as the presidential peace adviser. But, P-Noy decided to leave matters entirely in the hands of Ging Deles, such that she became Alex’s “boss”. Patay na.

When the talks formally resumed in February 2011, the two panels reaffirmed the previously signed agreements but the GRP panel did so “with reservations”. Deles (with Alex seconding) called The Hague Joint Declaration as a “document of perpetual division”, labelled the CARHRIHL as “CPP propaganda”, and declared the JASIG “inoperative”. Thus the peace negotiations were abandoned by the GRP — but not formally terminated.

Ging Delez also used the OPAPP (Office of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process) for counterinsurgency, fully buttressing Oplan Bayanihan with her own program liberally funded with billions of pesos. Apparently some policies and the programs that were instituted during her time are being carried out by Duterte’s peace adviser, Jesus Dureza.

L: How influential is OPAPP in the talks?

SO: OPAPP, during the time of Ramos, had no role in direct negotiations. It implemented programs for rebel returnees. It became powerful during the second Aquino government. Under Duterte, OPAPP chief Jess Dureza works in tandem with GRP panel chair Bebot Bello, but clearly asserts a louder voice than the chief negotiator.

Both are Duterte’s close friends. But I observed that they had been amiss, particularly at critical junctures of the peace negotiations, for failing to immediately brief the President on the status or results of each round of negotiations. Such shortcoming on their part has resulted in Duterte blustering and making pronouncements that created problems and disrupted the negotiations — such as what happened in February — and he needed to walk back on his blusterings to put things aright later.

In light of the present impasse, I would suggest that Jess and Bebot, who both have invested so much time and efforts in the peace talks since Ramos’ watch, to persuade and convince the President to continue and complete the formal negotiations on CASER and CAPCR (Comprehensive Agreement on Political and Consitutional Reforms) the soonest possible time, as they had committed to do. There are those within the government who want to sabotage the negotiations. Jess and Bebot should assert that completing the negotiations, and more importantly implementing them would give great credit to the Duterte government. Wasn’t Bebot saying until recently that the GRP-NDFP peace negotiations could be the best legacy of Pres. Duterte to the Filipino people? And hadn’t Jess been repeatedly hailing Duterte’s “deep passion for peace”?

L: While you were not part of the negotiaing panel, what support do you give them?

SO: I continue to monitor the peace negotiations, and make myself available to assist in whatever way I can. As a weekly columnist for a major daily, I have written several pieces reporting on the peace talks, analyzing and explaining what I deemed to be important points the readers needed to know. And I continue to speak at various forums providing updates, analysis and explanations on critical issues.

L: What can you say about the talks with the Duterte government, where is this heading?

SO: Cooperation between the two panels is important. They should both be strong and maintain principled stand against the countervailing pressures and maneuvers of those who want to derail the progress of the negotiations on social and economic reforms by insisting on giving primacy to a prolonged bilateral ceasefire. But the GRP panel, led by the OPAPP, tends to go soft on the issue.

Midway through the rounds of talks, the NDFP registered clearly it was open to signing an interim ceasefire agreement immediately after the CASER is signed, not before. The GRP panel agreed but later gave the feedback that those in the cabinet security cluster were insistent on the signing of a ceasefire ahead of the CASER. Clearly there’s a tug of war within the cabinet, and Duterte has tended to go along his security advisers.

The insistence on a joint ceasefire disturbed the relatively smooth flow of the first to the fourth rounds of talks, and led to the cancellation of the fifth round. The fourth round already began somewhat rocky. Were it not for the ceasefire imbroglio, the negotiations on social and economic reforms could have advanced much further and President Duterte could have presented a positive report on the peace talks in his second SONA, rather than go blustering that he no longer wanted to talk peace with the Left.

L: What is the role of the mass movement in the peace talks?

SO: The open democratic mass movement, along with the various peace advocacy groups supporting the agenda for fundamental reforms, has played a significant role in the peace talks. It has helped a lot in justifying the need for peace talks and in popularizing the vital issues being discussed and negotiated on that affect the lives and the future of our people, especially the poor. And whenever there occurs a breakdown or impasse, the mass movement has largely provided the needed pressure on the two sides—particularly on the government that has always caused the breakdown or impasse—to resume negotiations and to stick to the agreed-on substantive agenda.

L: What have we gained from the peace talks?

SO: The signing and repeated reaffirmation of previous agreements have ensured the sustained path of the peace talks, no matter the interruptions. Also a perusal of all the signed agreements, foremost of which is the CARHRIHL, will show how serious, responsible, diligent and far-seeing has been the NDFP and all the revolutionary forces it represents, in their pursuit of a just and lasting peace. And all through the ups and downs of the peace talks the NDFP has shown durability and perseverance in taking and fighting for the correct positions.

Much of these we owe to the dedication of the panel members who have grown old on the job. We also owe these to the consultants, staff, and researchers, everybody working with the panel to formulate well crafted proposals and to link directly with the masses and explain the issues to them, solicit their inputs, thus involving them in the negotiations.

L: Are you still “enjoying” the talks? Aren’t you exhausted?

SO: We shouldn’t get tired in the pursuit of peace. We already have a good grasp of the dynamics of both parties, of the reactionary governments we’ve had negotiated with. The most important thing is that we are able to adjust our negotiating tactics to changing conditions or sudden twists, how to give and take without sacrificing our principles—ever upholding the people’s interests and welfare.

For a while we thought this government is the best among all previous administrations to work with in pushing for basic reforms, given how Duterte evinced such willingness to take the Left as its partner for change. It’s mainly up to him now what to do with the stalled peace negotiations as vehicle for such partnership. He knows he has very limited time, five years. He wants a change in the Constitution to shift to a federal form of government. Despite questions on some aspects of federalism, the NDFP offered to co-found the federal government he envisions, provided it does away with political dynasties, warlords and other exploitative, oppressive, anti-people elements.

If Duterte is looking for an ally, with a capacity to consistently think of what’s best for the country, then he should look to the Left, not to the traditional politicians who are only after their personal interests. From his decades-long experience, he knows that the Left is the only force the people can rely on to consistently fight for their interests and welfare. There have been many sacrifices in the almost 50 years of the people’s war and the leaders of the movement have been proven to be devoid of personal ambitions. Many have spent their whole lives in the movement and the movement has systematically ensured capable replacements. Eventually, the turning point of our development as a nation will be attained with the Left.

(Part 3 of 3)

Illustration by Ka Bam

(Part 2 of 3)

Illustration by Ka Bam

[…] September 9, 2017 […]

[…] September 9, 2017 […]