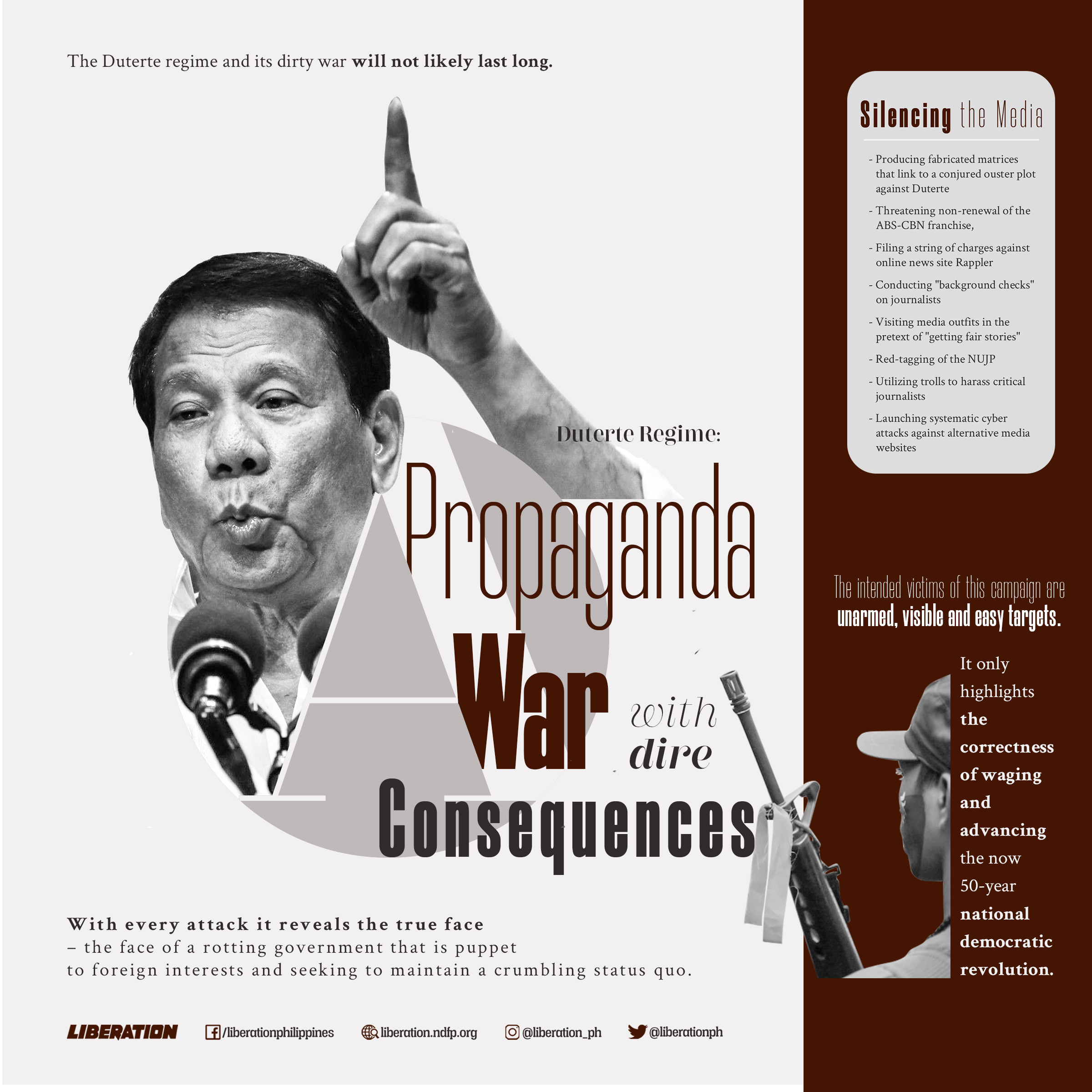

DUTERTE REGIME: A propaganda war with dire consequences

by Erika Hernandez

Neophyte Senator Ronaldo “Bato” dela Rosa, the controversial Philippine National Police chief of the Duterte government, recently led a public inquiry in the Senate and instantly spurred controversy and criticisms. He attempted to link progressive youth organizations with the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and the New People’s Army (NPA).

He presented two witnesses who claimed they were “students by day and NPA by night”—a giveaway phrase as to where it came from: the military. That he sought to turn a public inquiry, purportedly in aid of legislation, into a witch hunt immediately became obvious.

The frontman in President Rodrigo Duterte’s “war on drugs” also presented parents of youth activists, who apparently had been goaded to vilify leaders of Anakbayan and Kabataan Partylist as “kidnappers who brainwash their members.” Bato’s witch hunt came with memes on social media showing NPA martyrs from the youth sector and victims of state-perpetrated enforced disappearances with a theme, “Sayang ang buhay ng kabataan (Youth lives just wasted).”

Military officers, who had been invited as resource persons, called for a review of an agreement between a youth leader and then defense minister Juan Ponce Enrile, prohibiting the presence of state security forces in the universities and colleges. They gave lame excuses, such as to prevent “front organizations” from recruiting students to join the NPA; avert the proliferation of drugs in schools; and give the military an equal opportunity to explain government programs.

Following the Senate inquiry, members of the PNP attempted to conduct “mandatory” drug testing on students at the Polytechnic University of the Philippines (PUP). Courageous PUP scholars who knew their rights valiantly resisted, driving away the cops from the university premises.

Bato couldn’t wait to use the Senate as platform for pushing the propaganda line against the CPP-NPA of the Duterte regime in its bid to defeat the revolutionary movement before the end of its term.

By striving to directly link the progressive youth organizations with the CPP-NPA and the armed struggle against the reactionary state, the fascist regime aims to justify its red-tagging, harassment, abductions, and killings of youth leaders and activists. The regime blurs—if not totally removes—the distinction between the armed revolutionary movement and the legal, above-ground democratic mass movement fighting for the people’s legitimate demands. It regards the open democratic mass movement as the propaganda component of the armed revolutionary movement.

Thus in the following weeks, the Duterte regime’s red-tagging spree, branding almost all legal organizations as “fronts” of the CPP-NPA, was raised a notch higher. Duterte’s rabid pro-US defense chief urged the illegalization of these organizations by reviving the Anti-Subversion Act of 1957 (the cold war-era legislation that illegalized the CPP; it was repealed under the Ramos government in 1992 as it entered into peace negotiations with the NDFP).

Myth-making through red tags and incessant lies

Red tagging and vilification of people’s organizations is a key facet of the “strategic communication” thrust under the “whole of nation approach (WNA)” of the Duterte regime’s counterinsurgency program. Under this overarching WNA concept—applied unsuccessfully by the US in its unending wars of intervention in Afghanistan and Iraq since 2001 and 2002—the regime seeks to “create a movement of and crusade against communist ideology starting with the youth.” It also aims to “assess and conduct counter measures on the current tri-media and social media being infiltrated and targeted by the “CNN [CPP-NPA-NDFP)” through inter-agency collaboration to counter and contain the spread of extremism and revolution.”

What the regime is trying to portray is a supposed state inter-agency collaboration with civil society collaboration against the Left revolutionary movement. While Bato exploits the Senate as platform, Congress is poised to enact repressive measures such as the revival of the Anti-Subversion Law, amendments to the Human Security Act of 2007 (the anti-terrorism law), mandatory military training in schools, among others. The Anti-Subversion Law and Human Security Act amendments portray critics and activists as “terrorists,” to justify unrelenting unarmed and armed attacks against them.

Red-tagging and vilification have preceded many cases of extrajudicial killing, torture, arrest and detention and other human rights abuses against farmers, workers, environmentalists, Church people, lawyers, human rights defenders and other sectors.

The Duterte regime’s propaganda machinery involves both the military and civilian bureaucracy, with the former taking the lead role. The composition of the National Task Force to End the Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC), formed through Executive Order No. 70 and headed by President Duterte, shows how civilian agencies are being mobilized for counterinsurgency operations.

The NTF has been busy in its efforts to red tag and vilify the legal and progressive mass organizations critical of the Duterte regime and its continuing subservience to US imperialism and obeisance to China as the rising imperialist power.

One of the most glaring incidents of red-tagging happened during the May 2019 elections. PNP men and women in uniform were caught on camera in the act of distributing a PNP newsletter linking Makabayan Coalition-affiliated partylist groups to the underground revolutionary movement.

In other areas such as Panay, Negros, Davao, Cagayan de Oro, leaflets containing a list of persons alleged to be communists were distributed by state agents. In the list are human rights activists, lawyers, members of the religious, journalists, and academics.

Brig. Gen. Antonio Parlade, AFP deputy chief of staff for civil-military operations, is one of the most vociferous in publicly labeling human rights organizations and sectoral groups as “CPP-NPA fronts” and in peddling the lie that these organizations are involved in “terroristic” activities.

The regime also takes advantage of social media to vilify its the most vocal critics. The Philippine News Agency (PNA) and the Presidential Communications Operations Office (PCOO) makes use of fake photos, fake statements, and incredible claims against leaders of the people’s organizations.

The regime has spent tremendous amounts of taxpayers’ money in disseminating its propaganda against the progressive movement to the international community. The NTF-ELCAC went as far as dispatching a team that visited officials of European Union (EU) member states to red-tag Karapatan, Ibon International, Rural Missionaries of the Philippines, Gabriela, among others. The task force urged these EU countries to cut funding for organizations serving the most neglected rural communities in the Philippines.

The NTF-ELCAC sent a delegation to the United Nations Working Group on Involuntary Disappearances in Bosnia-Herzegovina and egregiously urged that body to delist 625 cases of enforced disappearances in the Philippines, mostly attributed to state security forces. NTF members also furiously lobbied against the passage of a resolution filed by Iceland in the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC), urging the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to look into the spate of extrajudicial killings and make a written comprehensive report on the human rights situation in the Philippines. Their lobbying failed; the UNHRC adopted the resolution.

Even the academe, hospitals and other civilian agencies are not spared from the witch hunt. Policemen did rounds in schools, government hospitals and other offices, profiling the members and officers of employees’ unions.

The AFP and PNP have been spreading outright lies. They claim to have succeeded in ending the “insurgency” in some provinces—claims that have repeatedly been belied since the Ramos government first declared, in 1994, that it had strategically defeated the NPA (which it admitted to be untrue several months later). They present to the media fake surrenderers, mostly farmers they either coerced, deceived, or bribed—through the Enhanced Comprehensive Local Integration Program (E-CLIP)—into admitting they were NPA members. They churn out these falsehoods to conjure the illusion that they are winning against the revolutionaries.

But when their most heinous crimes are exposed, they readily put the blame on the CPP- NPA. This has been shown in the case of the extrajudicial killings in Negros Oriental. Braving threats and the pain of repeatedly recalling the tragic massacres, families of the victims have testified how their loved ones were killed in cold blood during the joint AFP-PNP’s Oplan Sauron operations.

When members and other paid elements of the AFP and the PNP get killed in legitimate armed encounters, they try hide their defeats, or worse, misrepresent these incidents as violations by the NPA of international humanitarian law.

Criminalizing dissent: the biggest lie

Through the Inter-Agency Committee on Legal Action (IACLA), the AFP and the PNP jointly try to use the judiciary as a weapon against critics of Duterte and his corrupt and bungling regime. The following are just some examples showing how this administration is criminalizing dissent: the perjury charges filed by Gen. Hermogenes Esperon, the president’s national security adviser, against Karapatan, the RMP, and Gabriela; the sedition and cyberlibel cases filed against Vice President Leni Robredo, political opposition candidates in the May senatorial elections, and some Catholic bishops; and, the kidnapping charges against youth leaders and former Bayan Muna Rep. Neri Colmenares.

A similar ridiculous and malicious kidnapping and child abuse charges were earlier filed against Bayan Muna President Satur Ocampo and Representative France Castro of Act-Teachers partylist in late 2018, when they helped rescue Lumad students who had been forced out of their school that was shut down by the military.

A number of activists, service providers of progressive NGOs and organizers or campaigners of legal progressive organizations, have also been arrested based on patently made-up accusations including illegal possession of firearms and explosives. In most cases the arresting teams have planted the “evidence” in the activists’ bags they seized, in vehicles or residences as in the case of labor organizer Maoj Maga, long-time peace advocate and NDFP peace consultant Rey Claro Casambre, and NDFP peace consultants Vicente Ladlad, Adel Silva, and recently Esterlita Suaybaguio.

Professional “witnesses” or “surrenderers” dragooned as witnesses are used from one case to another to churn out false testimonies, almost always bordering on the ridiculous. The use of arrest warrants against “John Doe” and “Jane Doe” have become the norm to justify the illegal arrests of any targeted person.

The “multiple murder” case involving, as supposedly prime evidence, “travelling skeletons”—first allegedly dug up from a mass grave in Baybay, Leyte then years later supposedly dugged up again in Inopacan, Leyte—has been discredited and should have been laid to rest long ago.

But, no! The biggest legal fiction of Gloria Arroyo’s Inter-Agency Legal Action Group (IALAG)—the filing of trumped-up murder charges in 2007 against Ocampo (then Bayan Muna congressman) and several others was questioned before the Supreme Court, which granted Ocampo bail. However, the case awaited action by the highest tribunal for seven years. Only in 2014 did the SC, mostly with new justices sitting, referred the case for trial to a regional trial court. Then after hearings held over about five years, the prosecutors recently asked the court to issue warrants of arrest against 38 of the co-accused, including NDFP chief political consultant Jose Maria Sison. The court issued the warrants.

In another case, the Court of Appeals recently junked both the petition for writ of amparo and writ of habeas data filed by the National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers (NUPL) and a similar petition filed by Karapatan, RMP and Gabriela (the NUPL is the groups’ legal counsel). The parallel rulings indicate the sway of military influence on the judiciary. The rulings, issued by different CA divisions, practically denied the human rights defenders the legal remedies sought for their protection against political persecution and threats to their personal security and their lives.

Silencing the media

As part of its “strategic communication” strategy, the Duterte regime has been discrediting the journalism profession in an apparent bid to drown out the truth in media reporting and spread more lies. By calling journalists as bayaran, “press-titute”, and other derogatory labels, Duterte wants the Filipino people to doubt and reject the media’s role as watchdogs in society.

- The Duterte regime is trying to intimidate the more critical journalists using some of these methods: Producing fabricated matrices that link to a conjured ouster plot against Duterte the media organizations—the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP), the Vera Files, and the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ)—and individual journalists such as Inday Espina-Varona and Danilo Arao.

- Threatening non-renewal of the ABS-CBN franchise, a virtual Damocles sword on the broadcasting giant.

- Filing a string of charges against online news site Rappler and twice trying to detain its CEO.

- Conducting “background checks” on journalists. Members of the Philippine National Police Press Corps have reported police visits and interrogations.

- Visiting media outfits in the pretext of “getting fair stories” regarding the bloody war on drugs, such as in the case of two media outfits in the Visayas. Some journalists have been included in the drug watch list even though there is no evidence on the alleged use or trade in illegal drugs.

- Red-tagging of the NUJP, the largest organization of journalists in the country, for being vocal in its defense of press freedom. Individual members of the NUJP have also been red-tagged.

- Utilizing trolls to harass critical journalists. Some of these include, among others, death threats and threats of raping women journalists.

- Launching systematic cyber attacks against alternative media websites Bulatlat, Kodao, Altermidya, Pinoy Weekly and NUJP. The cyber attacks have also targeted the websites of Bayan, Karapatan, Bayan Muna, Gabriela Women’s Party, Ibon and scores of other organizations, including the CPP’s Philippine Revolution Web Central (PRWC). Sweden-based Qurium Media Foundation’s forensic report on the cyber attacks revealed that the attacks were launched on websites which are based in the Philippines.

The escalation of cyber attacks and vilification of media outfits, critical think tanks, progressive service-oriented NGOs and people’s organizations are also part of the Duterte regime’s “strategic communication” plan. The AFP first announced its creation of a cyber workforce in 2017. Since then until 2019, the AFP, the PNP and the Philippine Coast Guard have yearly held a Cybersecurity Summit.

Early this year, the Duterte regime launched a national cybersecurity plan. It created a cybersecurity management system “to monitor cyber threats,” headed by the Integrated Computer Systems (ICS) and the Israeli surveillance company Verint, with an initial licensing period of three years. Verint is a billion-dollar company with a global interception and surveillance empires.

The Duterte regime’s dirty propaganda tactics are coupled with heightening repression.

Labeling activists interchangeably as “terrorists,” “suspected drug addicts,” “kidnappers,” and the like aims to demonize and criminalize dissent and justify their killing and other human rights violations against them.

All these latest misuse of new technology to spread lies, combined with the age-old armed repression, are like carpetbombs seeking to harm not only the armed revolutionaries. Mostly targeted are citizens critical of the regime, the activists, the Church, the media and any other supporter of human rights and the struggle for genuine democracy.

The intended victims of this campaign are unarmed, visible and easy targets. The Duterte regime is fighting a truly dirty war. But the more it lies and kills even non-combatants, the more it reveals the bankruptcy of any promised good inuring to the people that it trots out to justify this dirty and costly war.

As such, the Duterte regime and its dirty war will not likely last long. With every attack it reveals its true face, the face of a rotting government that is puppet to foreign interests and seeking to maintain a crumbling status quo. It only highlights the correctness of waging and advancing the now 50-year national democratic revolution.

To break the cycle of lies and killings being perpetrated by this fascist regime, the people here and abroad should harness the courage and will power to expose and denounce its lies, and call for ever-broadening people’s resistance.###

#DuterTerorista

#FightTyranny

#DefendPressFreedom

#MakibakaWagMatakot

—–

VISIT and FOLLOW

Website: https://liberation.ndfp.info

Facebook: https://fb.com/liberationphilippines

Twitter: https://twitter.com/liberationph

Instagram: https://instagram.com/liberation_ph

L: So you were still in jail when Ramos became president?

L: So you were still in jail when Ramos became president?