Raling Iglap

by ARMAS (Artista at Manunulat para sa Sambayanan)

Enero, sa panulukan ng EDSA-Aurora

Ipinarada ang mga pulang bandila

Suporta sa usapang kapayapaan, ugatin ang kahirapan

Digmang bayan para sa makatarungang kapayapaan

– Enero 23, 2017 | Cubao, Quezon City

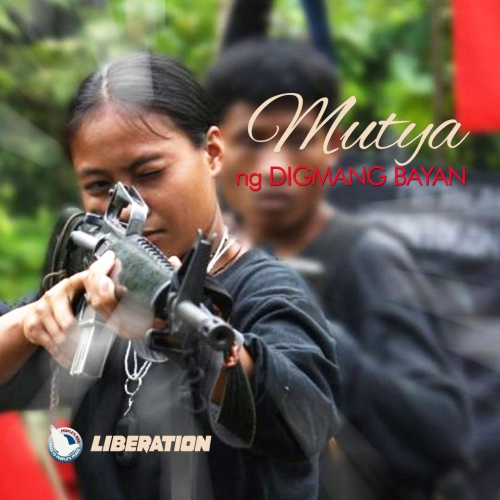

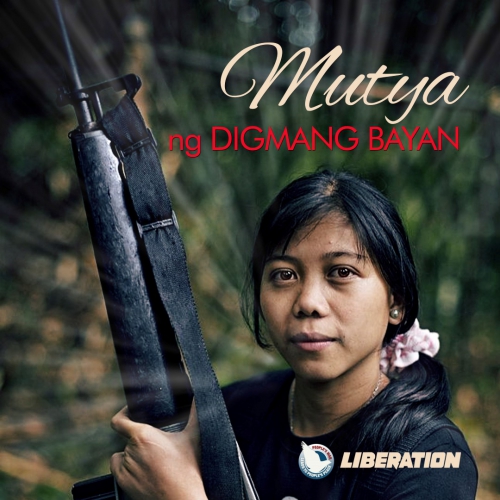

Sa may simbahan ng Quiapo, mga Bagong Kababaihan

Hawak ay hindi kandila, rosaryo, o dasal

Litanya ng pakikidigma ang binibigkas, inuusal

Hangad ay paglaya ng uring pinagsasamantalahan

– Marso 17, 2017 | Quiapo, Manila

Sa Sta. Cruz-Avenida sa Maynila

Makabayang guro ang nagmartsa

Itinuturo ang landas ng pakikibaka

Sa hukbong bayan sumapi, sumampa

– Marso 24, 2017 | Sta. Cruz, Manila

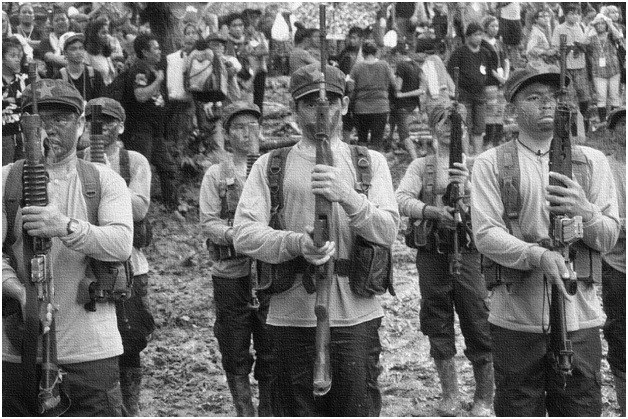

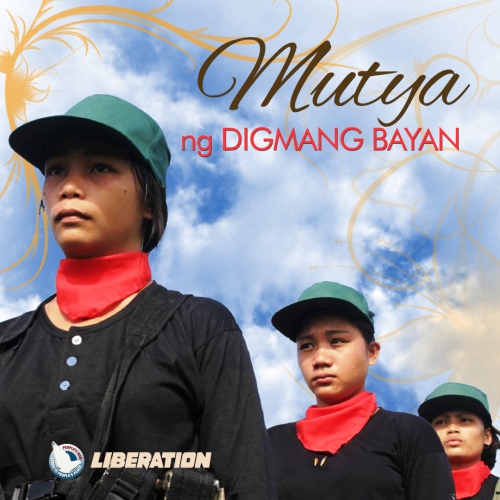

Itinanghal apatnapu’t walong taon ng pakikidigma

ng Bagong Hukbong Bayan sa kanto ng EDSA-Aurora

Armas ng mamamayang sinasamantala

Tagumpay ng rebolusyon ang panata

– Marso 27, 2017 | Cubao, Quezon City

Ipinagbunyi sa paanan ng Mendiola

Ikalawang Kongreso ng Partido Komunista

Marxismo-Leninismo-Maoismo ang gabay

Ibayong pagkakaisa, ibayong tagumpay

– Marso 31, 2017 | Mendiola, Manila

Strength and flexibility

Strength and flexibility