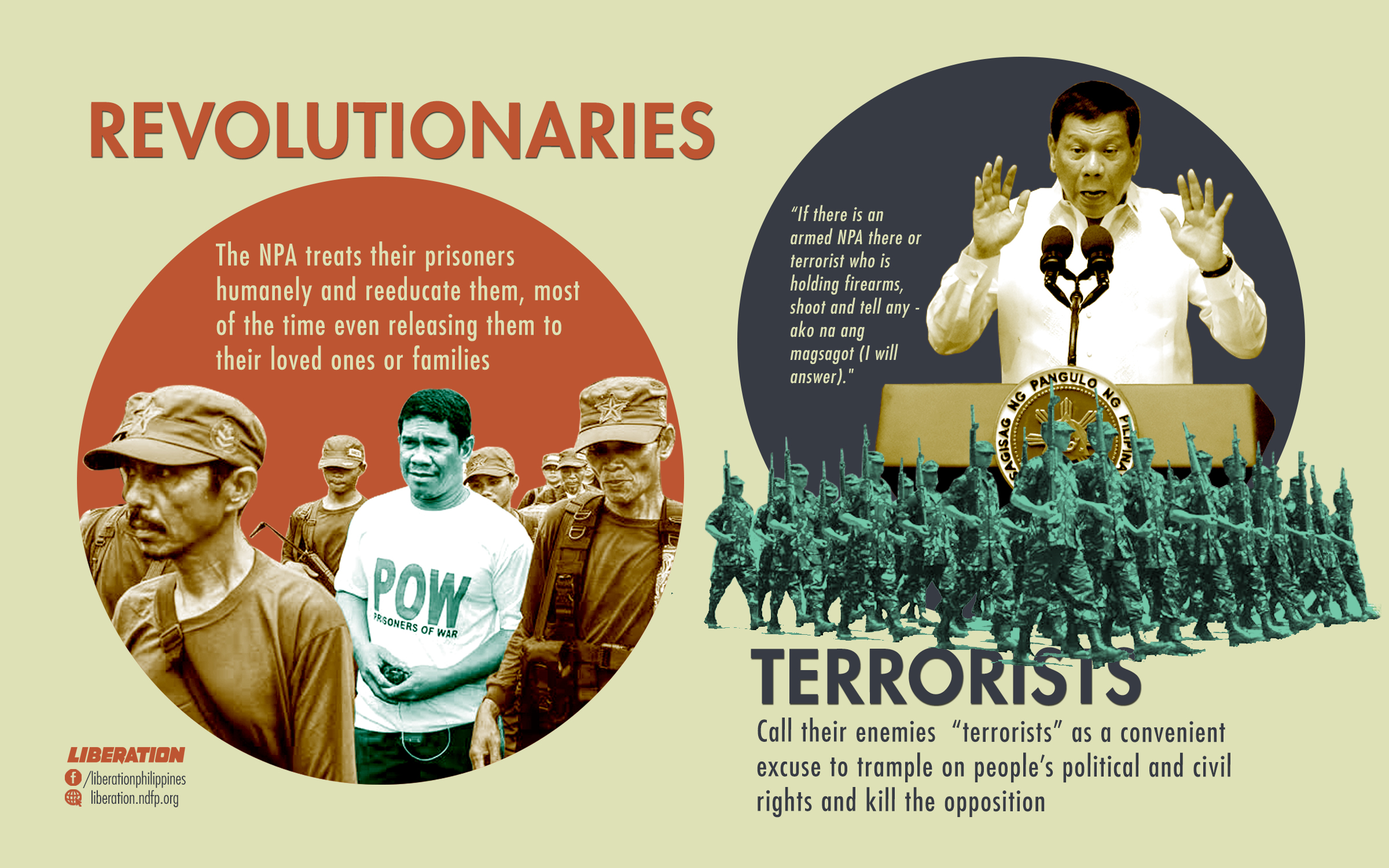

REVOLUTIONARIES NOT TERRORISTS: Terrorist-tagging is old hat

by Vida Gracias

In early December, days after he terminated the peace talks with the National Democratic Front of the Philippines, President Rodrigo Duterte formally declared as “terrorists” the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and the New People’s Army (NPA).

But for those who have grown with the revolution in the country for almost 50 years, the demonization of the CPP-NPA started way back since Marcos’ martial-law dictatorship. In fact the reactionary military—then and now—never stopped using the tag “Communist Terrorists” against real, suspected or imagined revolutionaries.

The terrorist tagging has resulted in an all-out war waged against not only the CPP-NPA but against the entire Filipino people—a war that has combined all the worst features of past and present counter-insurgency programs.

People in the countryside have been inured to seeing slogans on billboards, streamers on walls of houses and trees pointing to the NPA, and even to legal organizations, as “terrorists”. The media, including social media, has been utilized extensively to malign the CPP-NPA. But no matter how zealous current and past regimes have been in such demonization campaign, they have failed to make the tag stick on the CPP-NPA.

Why so? Because the CPP-NPA as a revolutionary force is a far cry from terrorists, who employ armed violence and brutality in wantonly killing people and destroying public facilities and private property to foment widespread fear among the populace. The CPP-NPA uses armed force in a revolutionary war against the reactionary state to seize political power and bring about fundamental social, economic and political changes beneficial to the people that would lead to attaining just and lasting peace.

All past regimes have failed to crush and defeat the CPP-NPA. Duterte, after all, was never a good student of history.