Ang Masa

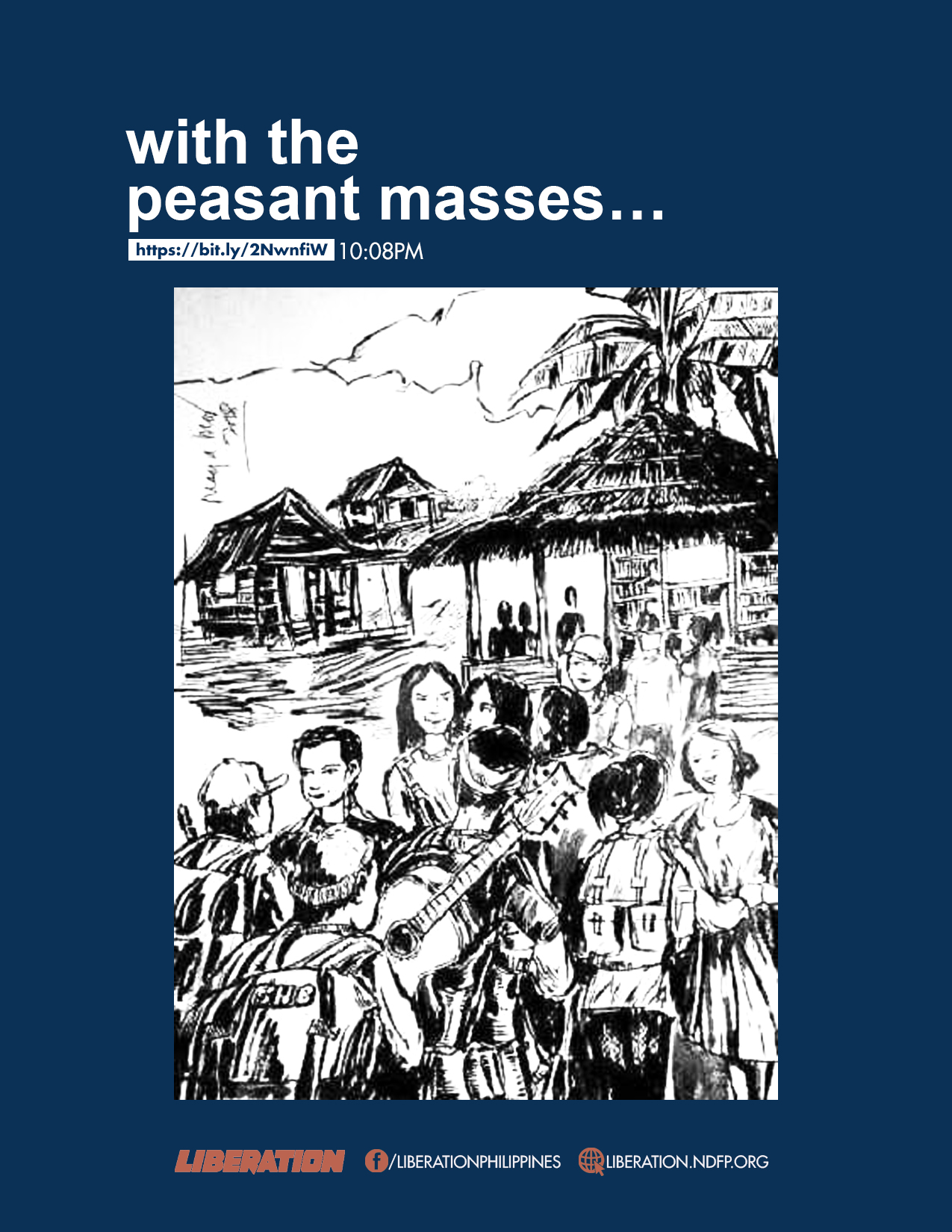

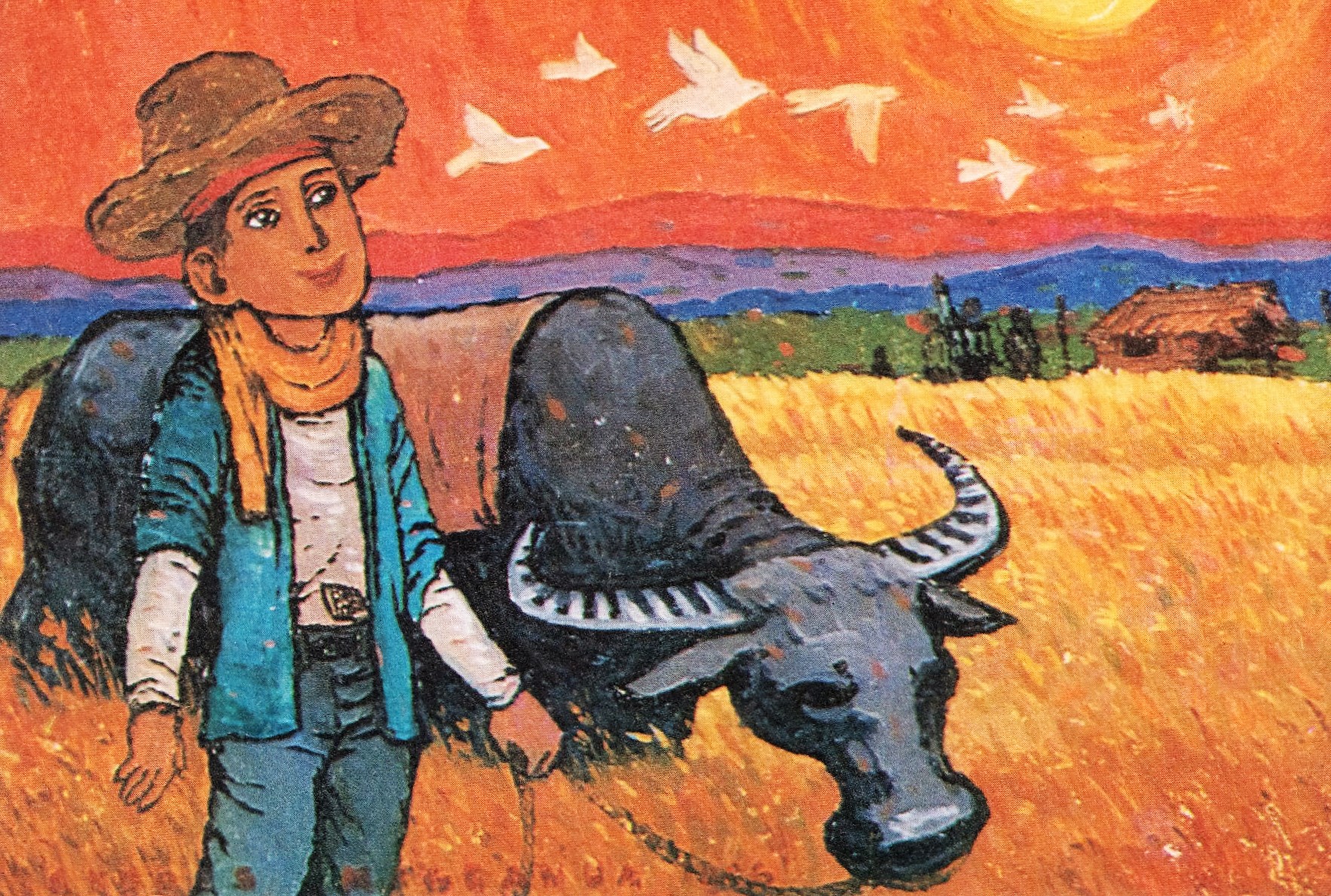

Kasalanang mortal ang pagmamaliit sa kakayahan ng masa na mag-isip at kumilos upang solusyonan ang nakapasan sa kanyang pagsasamantala at kahirapan.

Hindi sabwatan o pakana ng iilan ang magbabago sa lipunan. Ang masa ang magpapasya; sila ang lilikha ng kasaysayan.

#ServeThePeople

#NPArevolutionaries

#CPP50