Love a Revolutionary, Love the Revolution

by Trisha Sarmiento

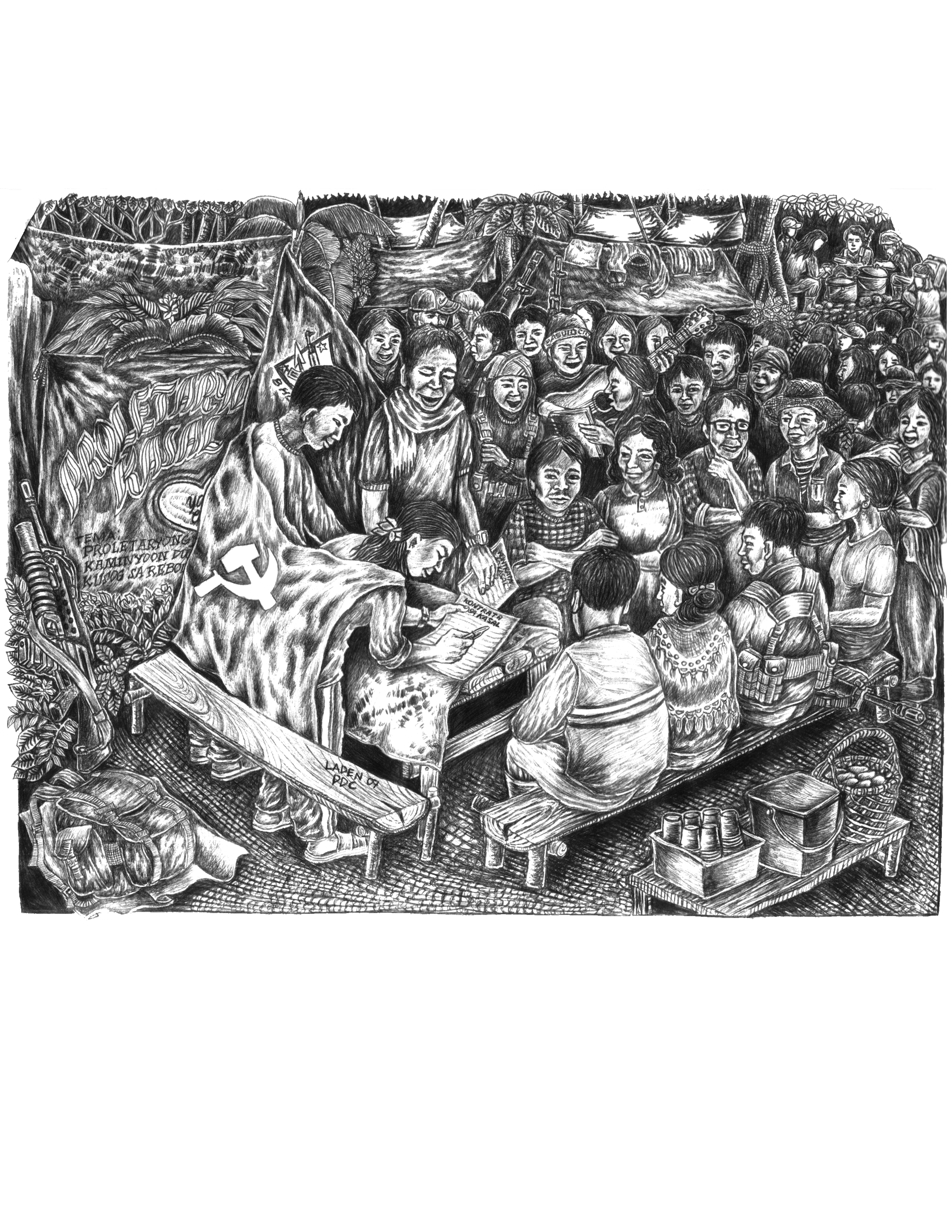

The cold wind, sturdy pine trees and the scenic mountain ranges of the Cordilleras in Northern Luzon set the perfect mood for the wedding of two guerrilla fighters of the New People’s Army (NPA). The ceremony was held March 29, 2017, right after the Cordillera NPA Regional Command, the Chadli Molintas Command, celebrated the NPA’s 48th founding anniversary.

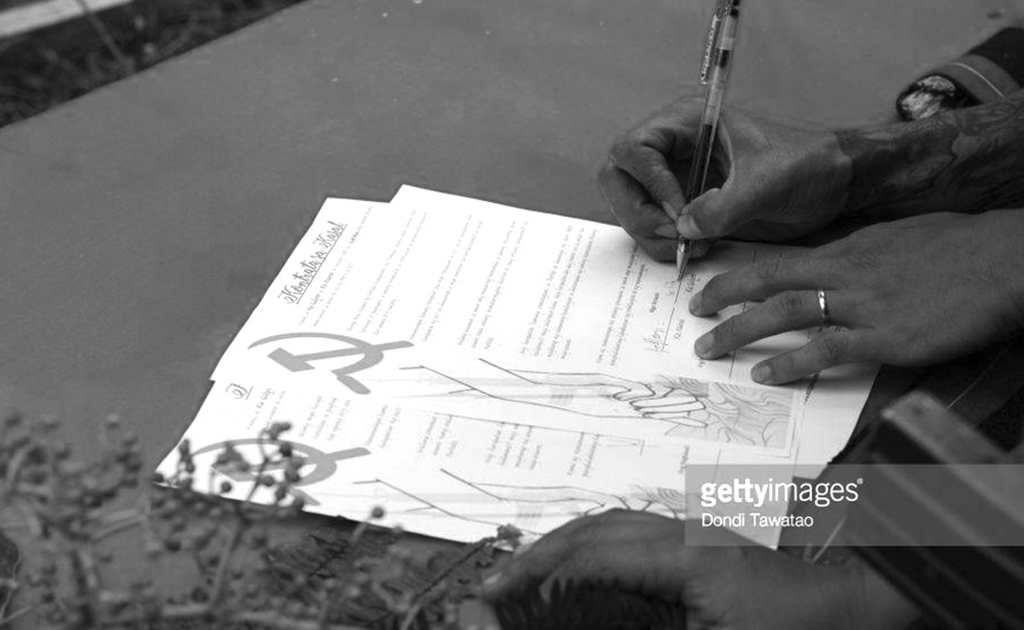

It was everything a wedding should be. The bride held a bouquet and wildflowers adorned the aisle for the bridal march. There was the exchange of marriage vows and the signing of the marriage contract issued by the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP). The couple also had the NPA’s version of the saber arch, counseling from the members of their collectives, and tips and advice from the wedding sponsors. The much-awaited first kiss of Ka Guiller and Ka Nancy as husband and wife sealed the promise of liberating love.

No ordinary love

Comrade Nancy joined the revolutionary armed movement in May 2014. Ka Guiller was her squad leader. The attraction between the two slowly developed as they carried out their political tasks in the NPA. They started to know each other really well. Later, Guiller would convince Nancy to become a full-time member of the NPA. Even when they were assigned to separate units, their attachment to each other grew stronger. Three months later, they found themselves in an “informal” relationship, meaning that their respective units or collectives had yet to approve of their relationship as required by the Party and NPA processes.

As part of NPA discipline, new recruits are dissuaded from entering into a relationship for at least a year to give them time to fully adjust to their tasks in the people’s army. But Guiller and Nancy pursued their relationship despite the restriction and caution from their respective units. This led to conflicts between them and between their units such that they decided to temporarily leave the people’s army.

Both went back to the city, and for more than a year, Ka Guiller and Ka Nancy actively took part in the urban mass movement before they sought the consent of their respective collectives to formalize their relationship. They went through deep-going criticism and self-criticism. While in the urban mass movement, the couple faced more problems and conflicts. However, they managed to overcome these obstacles with the support of their respective groups, but what impelled them more was the love they have nurtured for each other, for the masses and for the revolution.

And so, after one-and-a half years in the urban center and, after undergoing assessment and criticism and self-criticism sessions with their collectives, Ka Guiller and Ka Nancy decided to return to Cordillera to take part in the struggle they both truly love: to serve the revolution as full-time NPA fighters.

Months later, Ka Nancy and Ka Guiller exchanged vows in the presence of the Red fighters, their friends, and the rural masses.

“Marahas ang digma, pero mas marahas ang mga pinag-uugatan nito. Kapasyahan natin ang pagtahak sa landas na ito. Ang ating pagpili ay siyang ating pagtindig. Ang ating pagtindig ay atin ding panata. Panata, hindi lamang sa iyo, mahal, higit lalo sa bayan nating minamahal. Ang mga kabundukan ang ating paraisong tirahan, at sa piling ng minumutyang masa tayo ay napapanday.

“Marahas ang digma, pero mas marahas ang mga pinag-uugatan nito. Kapasyahan natin ang pagtahak sa landas na ito. Ang ating pagpili ay siyang ating pagtindig. Ang ating pagtindig ay atin ding panata. Panata, hindi lamang sa iyo, mahal, higit lalo sa bayan nating minamahal. Ang mga kabundukan ang ating paraisong tirahan, at sa piling ng minumutyang masa tayo ay napapanday.

Hanggang sa pagkakapatas,

Hanggang sa pagpula ng silangan,

Hanggang sa ganap na tagumpay.

Sa kahuli-hulihan, ikaw ay mananatili,

Ang aking katiwasayan sa gitna ng marahas na digmaan.”

(“War is cruel, but its roots are more violent. It is our choice to take this path. Our choice is our stand. Our stand is our commitment; a commitment, not only for you, my love, but most of all, for the people who we truly love. The mountains are our haven and with the masses, we are tempered.

Through stalemate,

When the east turns red,

To complete victory,

In the end, you remain,

My calm in a violent war.”)

“Nagmahal. Nagwasto. Nagtagumpay.” (We have loved. We have rectified. We have triumphed.).

These words sum up the love story of Guiller and Nancy.

Revolutionary love

Like all revolutionary couples, Ka Guiller and Ka Nancy adhere to the CPP policy on marriage and relationships laid down in the document “On Proletarian Relationship of Sexes” observed and followed since the 70s. In 1998, the policy was revised to include same-sex relationship and marriage apart from further discussions on courtship, marriage, divorce, and disciplinary actions. The NPA has its own guidelines based on the principles stated in the Party policy.

Without doubt, revolutionaries, like other individuals, do fall in love.

The difference is that revolutionaries express their love for each other in the context of the revolutionary interests of the people. While there is “sex love,” there is also “class love”, and the latter in fact is considered the principal aspect that defines the essence of their love. In the service of the revolution love springs, blooms and grows, hence love relationships cannot but serve and uphold the revolutionary aspirations of the Party and the proletariat. For revolutionaries, love is an integral part and a great expression of their revolutionary commitment.

Revolutionaries maintain the right to freely choose whom to love, but there are restrictions as well as responsibilities. “Free love”, “sexual freedom” or anarchy in relationships are strictly prohibited as this can lead to the violation of the rights of others, irresponsibility in the relationship, and breach of organizational discipline.

In short anarchism in love contradicts the revolution’s objective to establish a just society and the real equality of the sexes. Hence revolutionaries find the rationale behind the guiding principles of the Party on love, relationship and sex. Such principles draw a line between freedom and discipline, between rights and responsibilities, and between emotions and principles.

These principles aim to secure the interest of the Party and the revolution at all cost, protect the rights of every revolutionary and other individuals who may be involved, and advance a healthy proletarian relationship between couples inside the revolutionary movement.

Love a revolutionary

The dominant kind of love today is just a mere reflection of the existing social order and culture. In a semi-colonial and semi-feudal system, love can be oppressive, patriarchal and decadent in character, vulnerable to abuses and violations of the rights of others.

Revolutionaries know that to liberate love from oppression one must strive harder to revolutionize and liberate the entire unjust society. This is what the love story of Ka Guiller and Ka Nancy has shown.

And they are not alone. Revolutionary love blossoms in many NPA camps, farms, workplaces, campuses, communities and institutions where the national democratic revolution has taken its roots. Indeed, no love is sweeter and nobler than revolutionizing society in the company of one you truly love and want to share the rest of your life with. Hence loving a revolutionary is experiencing a kind of love that is selfless and liberating, guided and grounded so that it genuinely serves the people.